Paula Nicolin, Quodlibet, Macerata 2011 (270pp., €24)

Exhibits are like a house of cards; and it takes very little to make them collapse.

Giancarlo de Carlo's words from a June 11, 1968 article in the Unità open the new book by Paola Nicolin—dedicated to the XIV Triennale di Milano in 1968—who comes back to tackle problems of exhibitions and exhibition spaces [1].

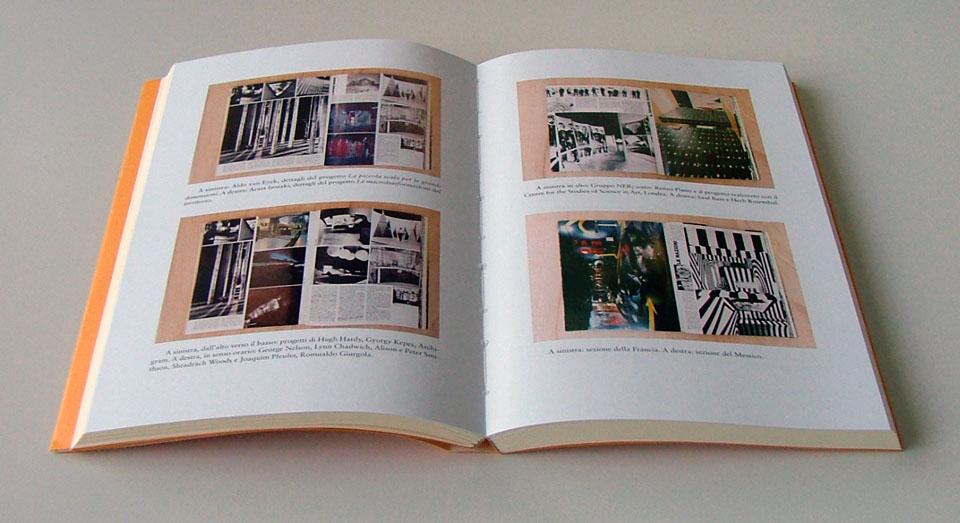

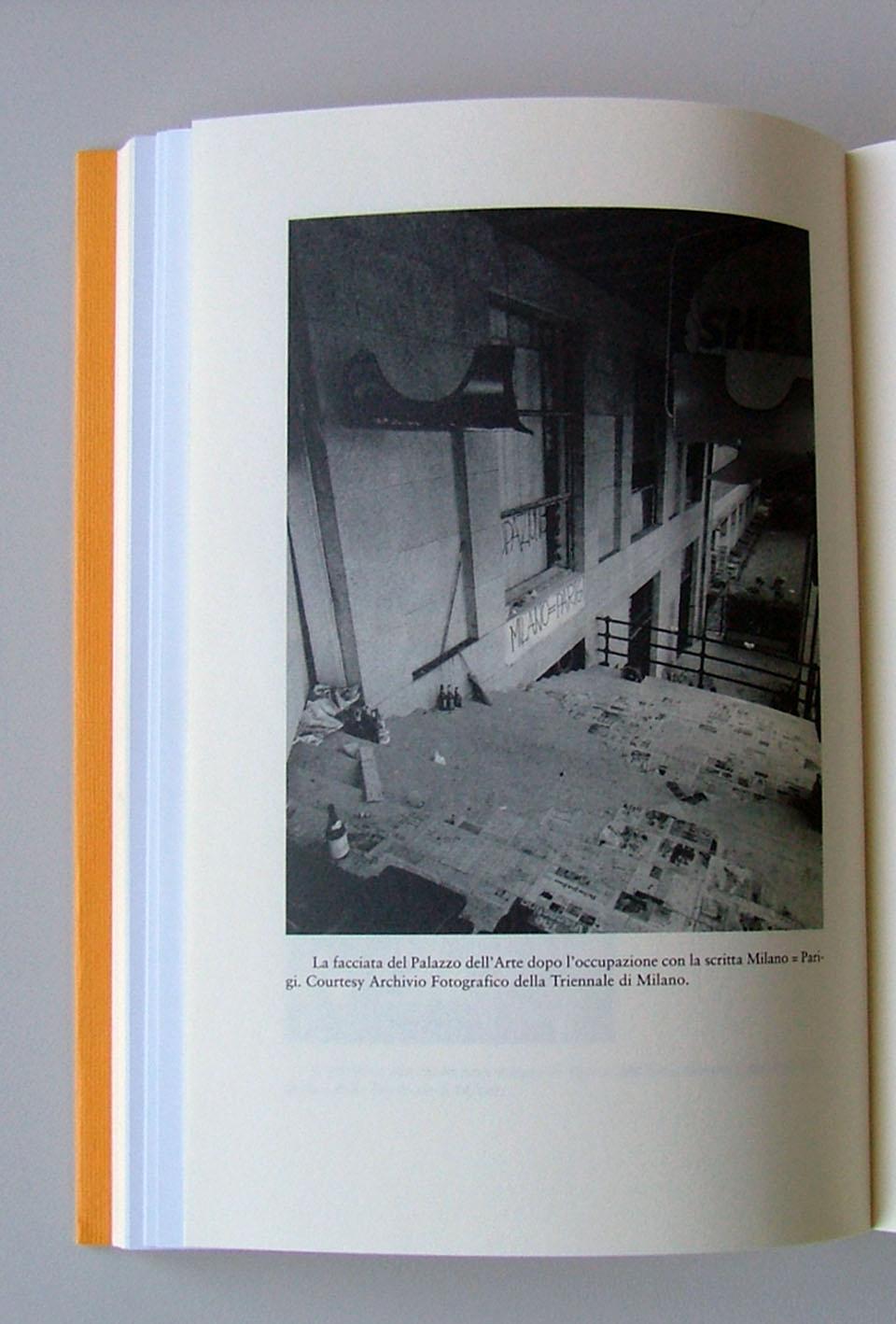

Born from a 2004 study by the author, Castelli di Carte takes its name from the definition of "exhibit" given by De Carlo, creator and organizer of the XIV Triennial and at the center of the dramatic images of the opening day protest [2], which ended with eviction on June 8 followed by the resignation of De Carlo along with the entire Executive Committee.

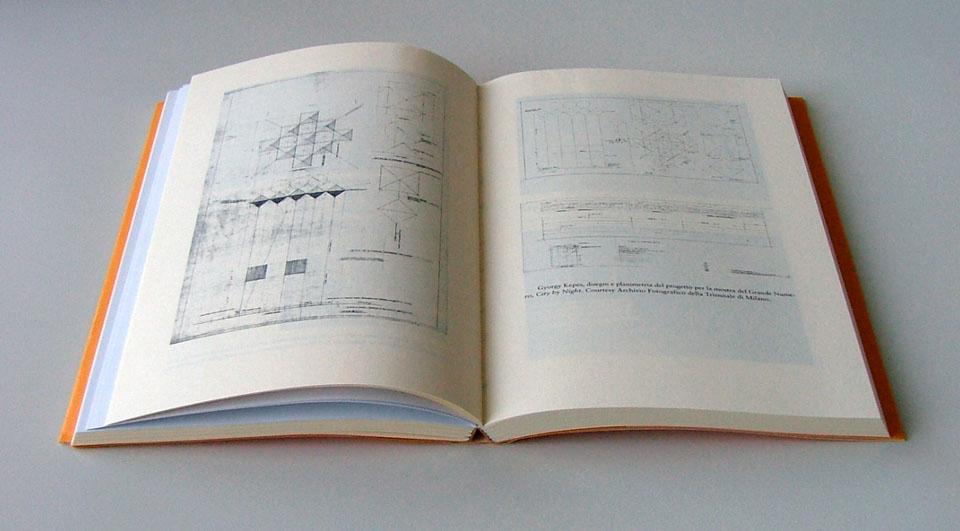

The book has the merit of bringing to light the hidden story of an exhibition seen by no one but discussed a great deal ("a rumour in the imaginations of those who had not even visited the show" [3]) through the collection of archival documents, the reconstruction of the exhibition design, direct testimony and rich bibliographical information.

The book has the merit of bringing to light the hidden story of an exhibition seen by no one but discussed a great deal through the collection of archival documents, the reconstruction of the exhibition design, direct testimony and rich bibliographical information.

The book also gives voice to some of the protagonists of the Triennale occupation a few weeks before that of the Venice Biennale, and concludes with three testimonials from the era: Ugo La Pietra, Gian Emilio Simonetti and David Boriani. The words of Boriani are of a somewhat disturbing topicality, "Milan competed with Paris and New York to become the leader in the field of the visual arts, but the city did not have a museum of contemporary art. Italian design was acclaimed throughout the world, but there were no design courses in the Italian universities (...) For a long time, an appeal had been made for the reform of the academies of fine arts, frozen by the 1926 Gentile law" [6].

NOTES:

[1] See Paola Nicolin, Palais de Tokyo. Sito di creazione contemporanea, Postmediabook, Milano 2006.

[2] See Domus 866, January 2004. The cover of the first issue under Stefano Boeri's direction was programmatically dedicated the the occupation of the XIV Triennale di Milano.

[3] Paola Nicolin, Castelli di Carte. La XIV Triennale di Milano, 1968; Quodlibet, Macerata 2011, p. 23.

[4] ibid, p. 27.

[5] Paola Nicolin, Castelli di Carte. La XIV Triennale di Milano, 1968; Quodlibet, Macerata 2011, p. 91.

[6] ibid, p. 256.

Anna Daneri is a contemporary art critic and curator.