The first edition of “Skulptur Projekte”, in 1977, was accompanied by controversy, and the same was also true for the second edition, in 1987. But starting in 1997 the inhabitants, overall, supported the event and today we can say they truly identify with it. The more monumental works distinguish the land whereas others remain in the collective memory. In this sense, the project has unquestionably reached its goal, creating curiosity, awareness, understanding and pride.

Financed by the city of Münster, by the Region and by various institutions and private entities, “Skulptur Projekte” is now in its fifth edition. Curated by Kasper König together with Britta Peters, a freelance curator from Hamburg, and Marianne Wagner, a contemporary art curator at LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur, it offers thirty-five new projects: sculptures, strictly speaking, but also installations and performances that blend in with the context. Today, it’s unthinkable to limit our notion of sculpture within conventional canons; moreover, while walking around the town you get the impression that the best works aren’t the more iconic ones but rather those related to specific architectural and socio-environmental situations. In short, the success of the works – be they permanent or temporary – depends on their ability to deeply become a part of the context while respecting its deep-rooted characteristics.

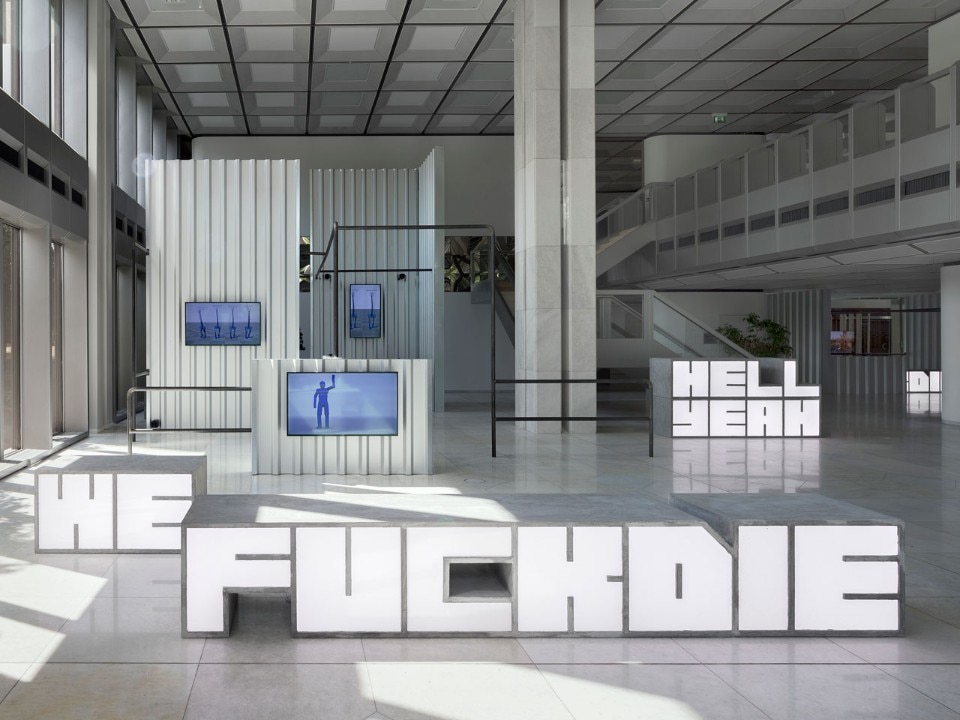

An example of the expansion of sculpture is the work HellYeahWeFuckDie by Hito Steyerl: a series of videos plus some structures intended to host them; everything is focused around a reflection on robotics and, more in general, the digital era as well as on the impact of technology with respect to the lives of humans as it has unfolded today. The work is located within the impressive entrance hall of the LBS West bank headquarters.

The work by Aram Bartholl is similar in theme but quite different in its development. It advances the fundamental question of our times: our way of life has made us utterly dependent upon technology, whose function, in turn, depends on energy sources. How can the effects of this dependency be negotiated? His three installations for Münster are based on a series of thermoelectric devices that transform fire, a source of life and primal communication tool, directly into electrical energy, also encouraging socialisation; as in the case of a bonfire around which people can unite to recharge their mobile phones or even to chat. His works are a memento, but they also stimulate reflection and indicate new possible beginnings.

Lara Favaretto directly faces the issue of the permanence of the work with her Momentary Monuments: works made up of sculptures in the shape of parallelepipeds with fissures into which coins can be inserted. The monoliths-piggy banks are intended to be destroyed, and their contents of coins, to be reused for different charities.

Nicole Eisenman’s beautiful fountain is classic in style but overwhelming in meaning. On its rim we find five human figures larger than reality; their happy and relaxing bodies represent a shift between genres and a possible new relationship with nature.

An expression of this expansion of sculpture is also Speak to the Earth and it will tell you by Jeremy Deller, who ten years ago, acting as a socio-anthropologist, invited some inhabitants with gardens to keep a diary; today, he displays the collection of over thirty-three large green notebooks, available for consultation, in a storage area in one of these veggie patches. While leafing through these, you get the feeling of great closeness to the lives that are not our own but which, flowing before us, generously come alive.

until 1 October 2017

Skulptur Projekte

various locations, Münster