These questions, and many more, are answered by the “Arena” exhibition held at the Center of Contemporary Art in Toruń, one of the most interesting Polish institutions devoted to contemporary art. Curator Dobrila Denegri, also acting as the program director of CoCA Toruń, skillfully avoided falling into any extremes. Politics – ubiquitous in the exhibition – has acquired a global, universal character, far from any local disputes. Plus the title adds a wider dimension to the exhibition. What is politics, other than a media spectacle?

Political events, such as wars or elections, are prevalent in information bulletins, producing an incessant show. Politicians themselves have acquired a social status comparable to art stars. They are equally often the speakers of the parliament, as they are invited to speak in breakfast television or floor shows. In this aspect, politics and art share a feature – they are both undergoing the process of dramatization, forming a scene for various options to clash. At the same time, both of these arenas are the litmus paper of the atmosphere in the society, of the economic condition, or the development of a given culture.

As a continuation of these words, Adrian Tranquilli presents his work, occupying entirely one of the rooms. “After the West” is a throne room, where columns are built from hundreds of masks of Guy Fawkes, a would-be killer who attempted at blowing off the British parliament 400 years ago, and who became a pop culture symbol of opposition towards the regime after the publication of the “V for Vendetta” comic book and movie. At this point, the mask has become an identifying symbol of the group of activists operating under the name Anonymous, opposing the restriction of civil freedom and censorship on the Internet, and it is the Internet that allows anyone to become an artist, having actual impact on political transformations conducted (see: the Arab Spring and its outburst was initiated through initiatives proposed on a social media portal). However, what is disturbing in Tranquilli’s installation is the empty throne…

The absence of authority? Power? Hence the absence of one vision setting forth the directions for the development of the world?

The “Arena” condenses its meanings in the main museum hall. The entrance is flanked by two twin works situated in side annexes. On the one side, we have “9/11 Frontpage” by Hans-Peter Feldmann, consisting of more than 100 newspaper covers from all around the globe, informing of the attack on the World Trade Center. This “live” broadcast of the attack, witnessed by the spectators is probably the most powerful sign of our times, when the images of collapsing towers have become the icons of the contemporary conflict of values.

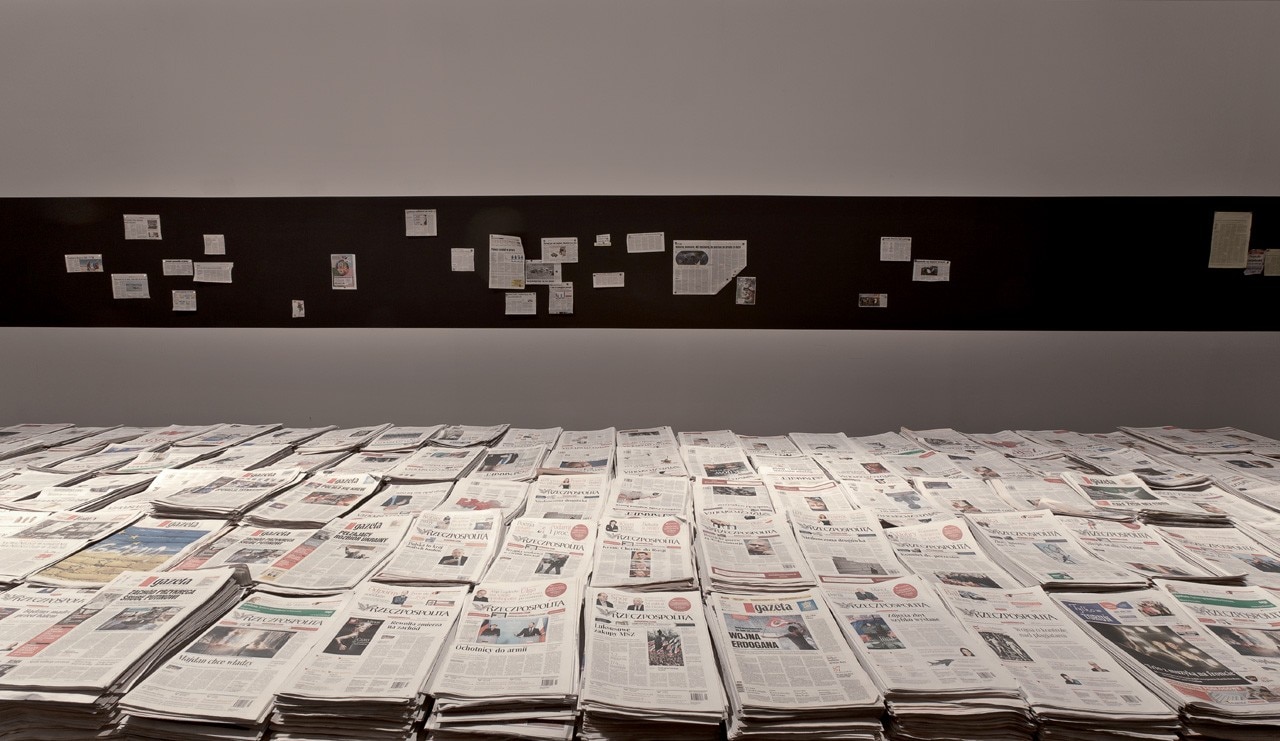

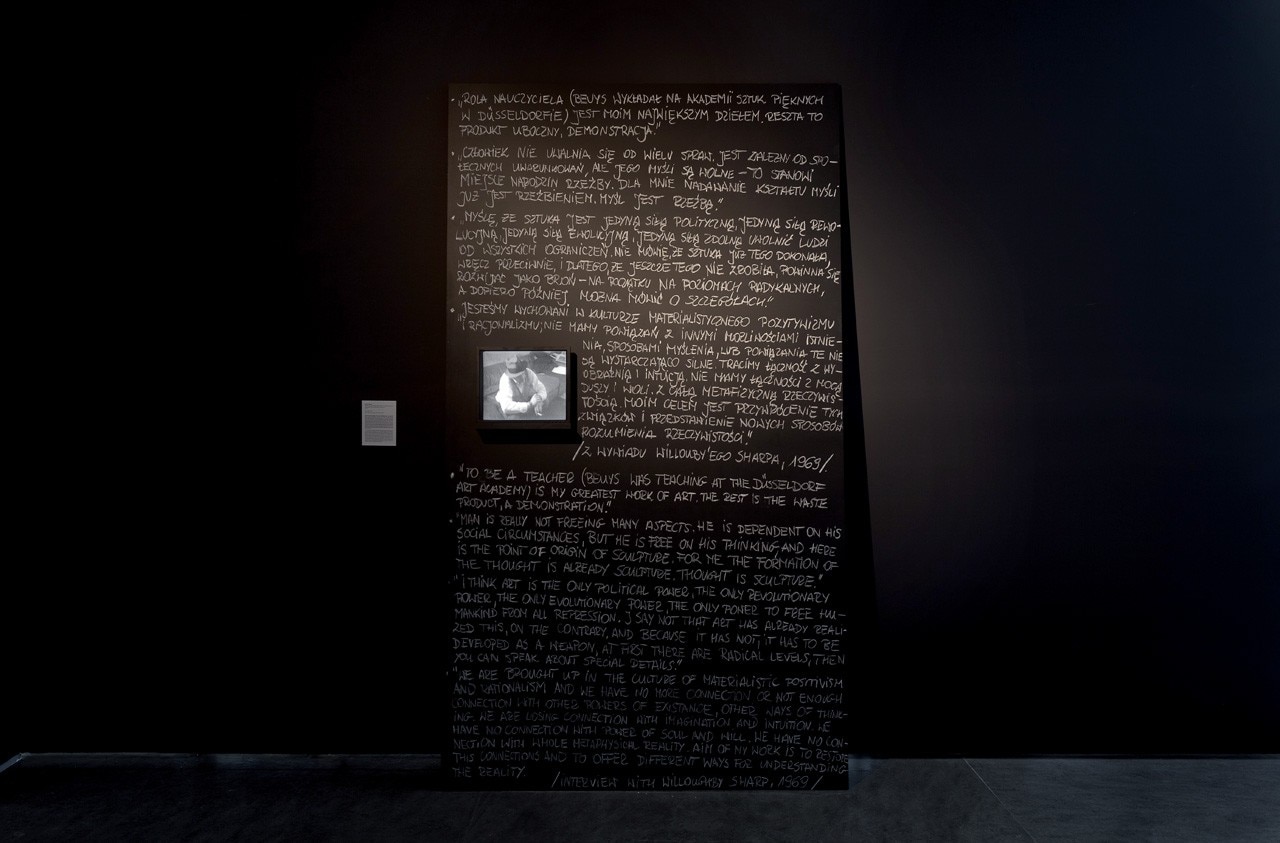

Feldmann’s piece is confronted with somehow a negative of his work – “Mass Media: today and yesterday” by Gustav Metzger features a stash of newspapers scattered all over the floor, serving as a field of interaction with the spectator. The walls of the annex are adapted to hanging press excerpts, headings, pictures. The visitors may cut out anything they like from the newspapers and create their own articles, newspaper issues. Today, not only anyone can be an artist, but also the co-author of media contents – as Metzger seems to suggest. Hence the natural question if art will once be governed by the pay-per-view principle or yet another, radical optimization of contents.