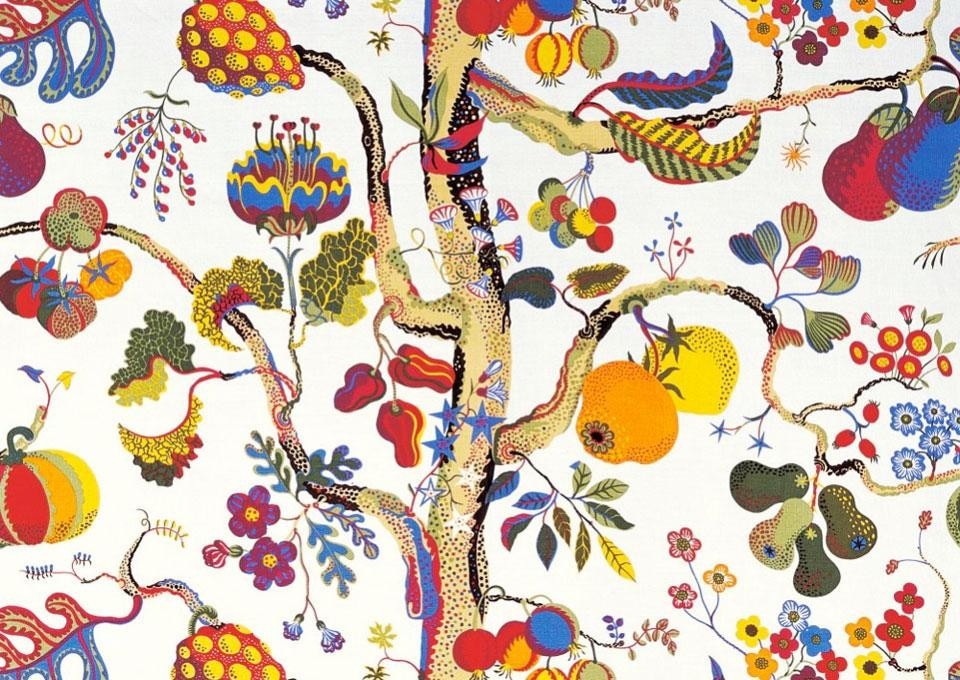

— Joseph Frank, 1930

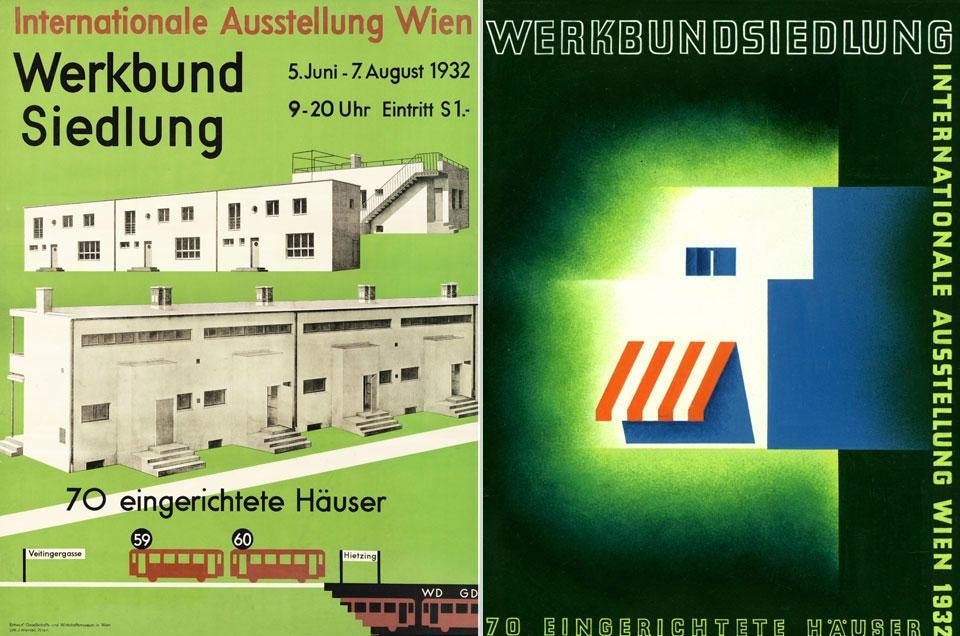

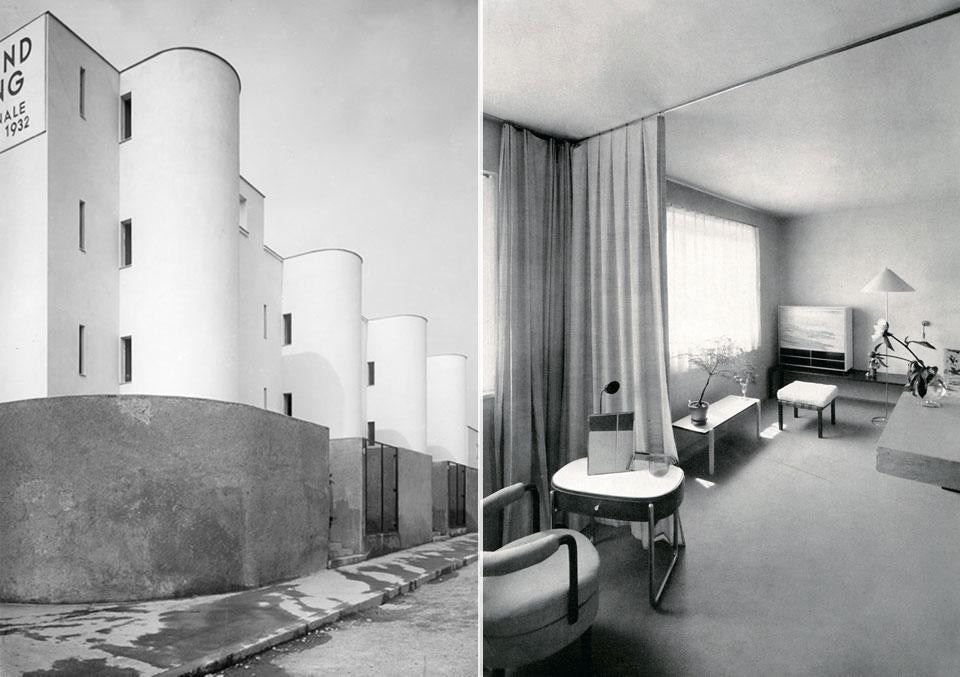

Werkbundsiedlung Vienna celebrates the 80th anniversary of the construction of the housing estate in Lainz, Vienna, launched as an international exhibition for residential construction in 1932. Thirty famed architects from Austria, Europe and America such as Richard Neutra, Adolf Loos, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, Otto Niedermoser, Ernst A. Plischke and Gerrit Rietveld completed 70 fully furnished houses for public display in the Werkbundsiedlung, before being made available for sale to potential residents. At the Wien Museum, the historical significance of this event and the maintenance of the estate is commemorated with detailed documentation in the form of photography, plans, models, sketches, interior furnishing, and even sale prices of the completed homes. As an initiative of the Austrian Werkbund within the framework the building activity of the Rotes Wien City of Vienna, the Werkbundsiedlung applied the glamour and capacity of these architects to this affordable housing project, departing from functionalism by prioritising colour, beauty and decorative elements.

Established in 1912 the Austrian Werkbund was an association of designers and craftspeople intended to work on both luxury and quality affordable design projects. With members such as Josef Frank, Adolf Loos, and Margarete Schütte Lihotzky, it shared an ideological premise with the Viennese social democratic govenment first elected in 1918 which was responding to local poverty and housing demand by initiating and realising a large scale building program. From 1925 more than 60000 apartments were constructed in Gemeindebau, or municipal housing. Funded from specially introduced taxes implemented by the finance minister Hugo Brietner, including a tax on luxury, the program was hugely successful, offering low cost rent controlled apartments at 4% of average income.

The exhibition easily represents the stylistic differences between the architects involved, but only hints at their philosophical differences. Chief manager Joseph Frank sought to use decor to distinguish between "staying" or "belonging" and "living" or "wohnen" and "leben". This could be seen as at odds with Adolf Loos' 1908 Ornament and Crime, where he claimed that "The evolution of culture depends on the elimination of ornamentation from commodities", meaning that ornament can cause objects to go out of style and thus become obsolete.

Under the direction of Werkbund architect Joseph Frank it proposed the housing of families in townhouses with a modest garden surrounded by green space in the periphery, rather than the indiscriminate grouping together of people in large apartments

Werkbundsiedlung Vienna 1932

Wien Museum

Karlsplatz 8, Vienna

The restyling of Fiandre’s historic headquarters

The project by Iosa Ghini Associati studio is the ultimate expression of the company’s products and philosophy. The result is a workspace meant to be lived in.