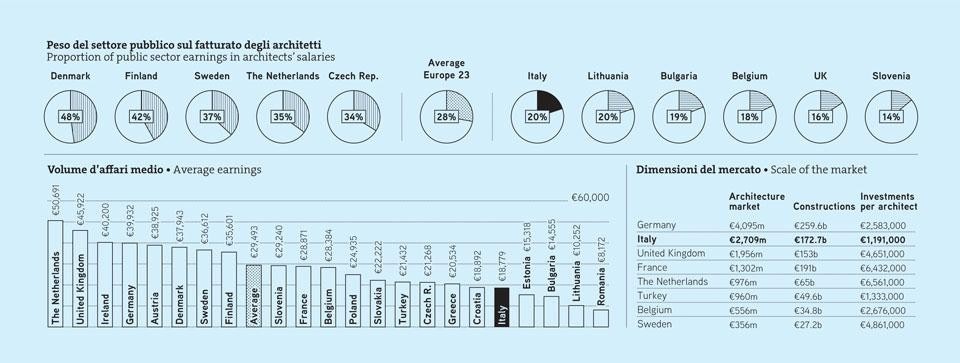

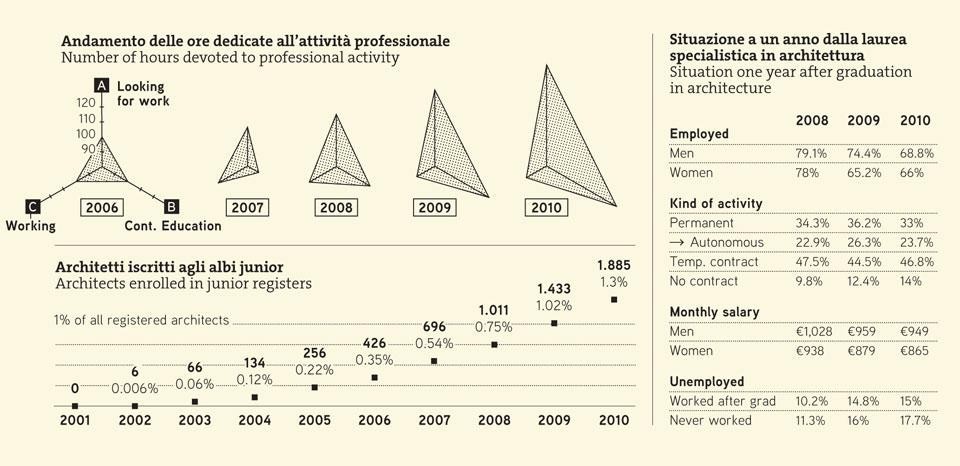

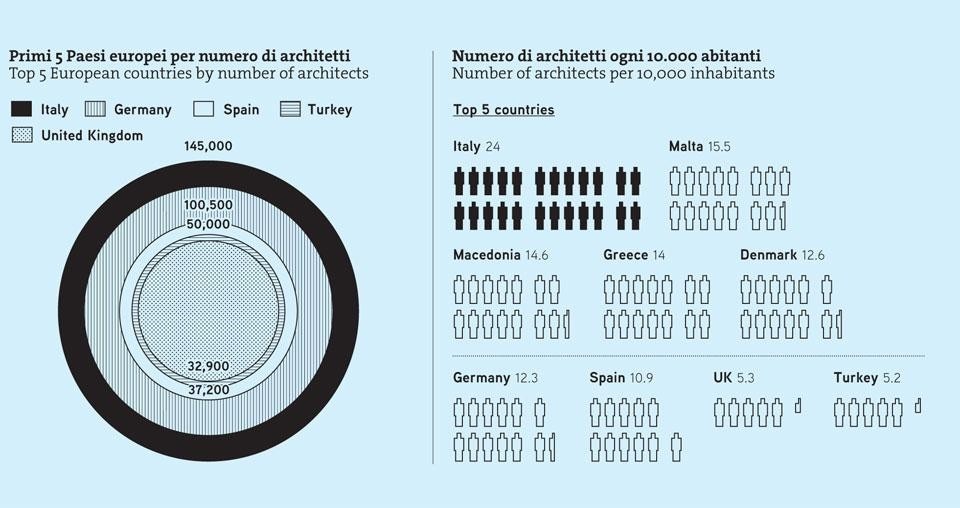

That Italians tend to consider whatever occurs in their (our) country to be anomalous is not exactly anything new. It has almost always been that way and, we might say, not always apropos. If there is one sector, however, in which Italy is undeniably unique it is architecture. For some years now, certain statistics have been reverberating in this field like disturbing mantras: one third of European architects are Italian.

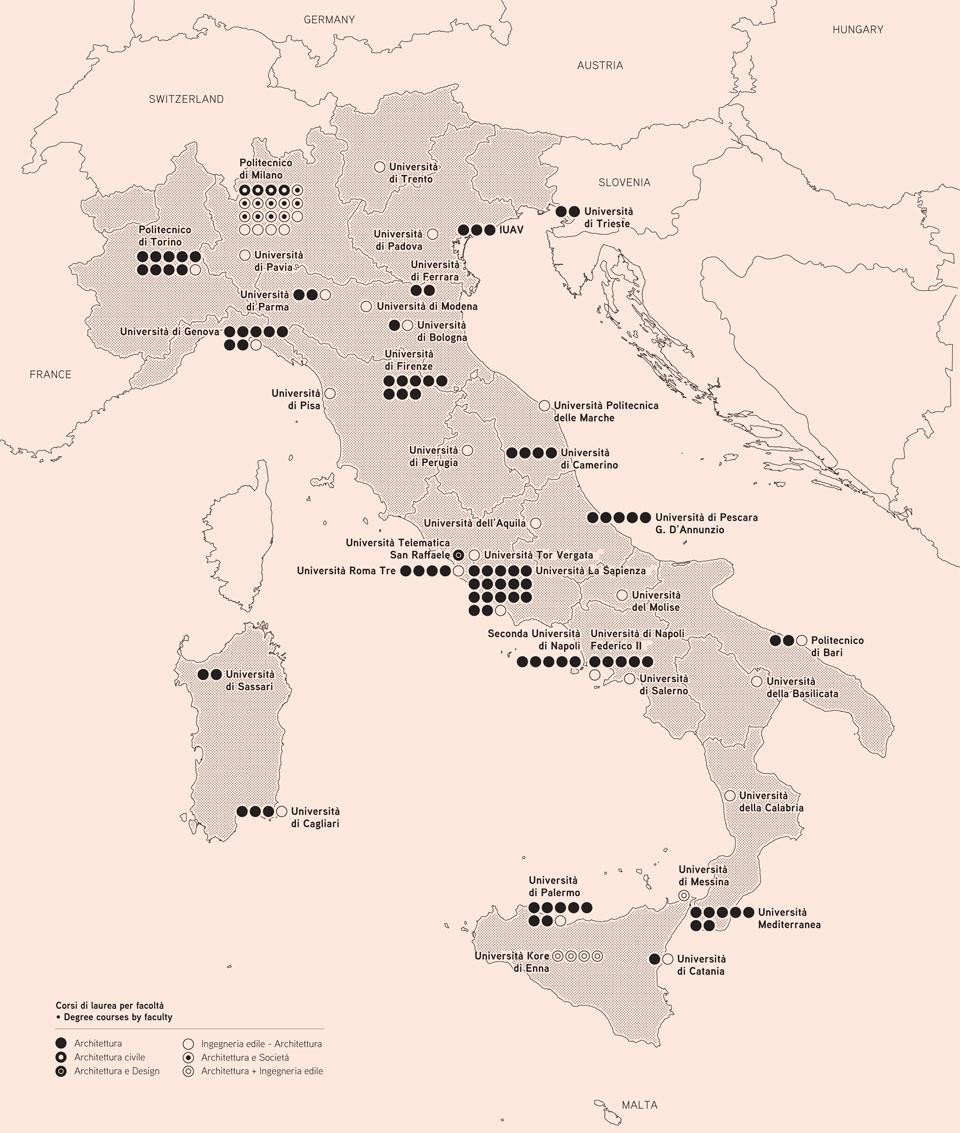

Nearly one tenth of all architects worldwide are Italian. There are more architects in Rome than in Sweden and Portugal combined. Yet the (well-known) fact is that the corresponding employment rates are far from even barely acceptable. It is clear that somewhere, something is not working or has not worked at a given moment in history. It is equally clear that a large part of the problem has to do with the universities.

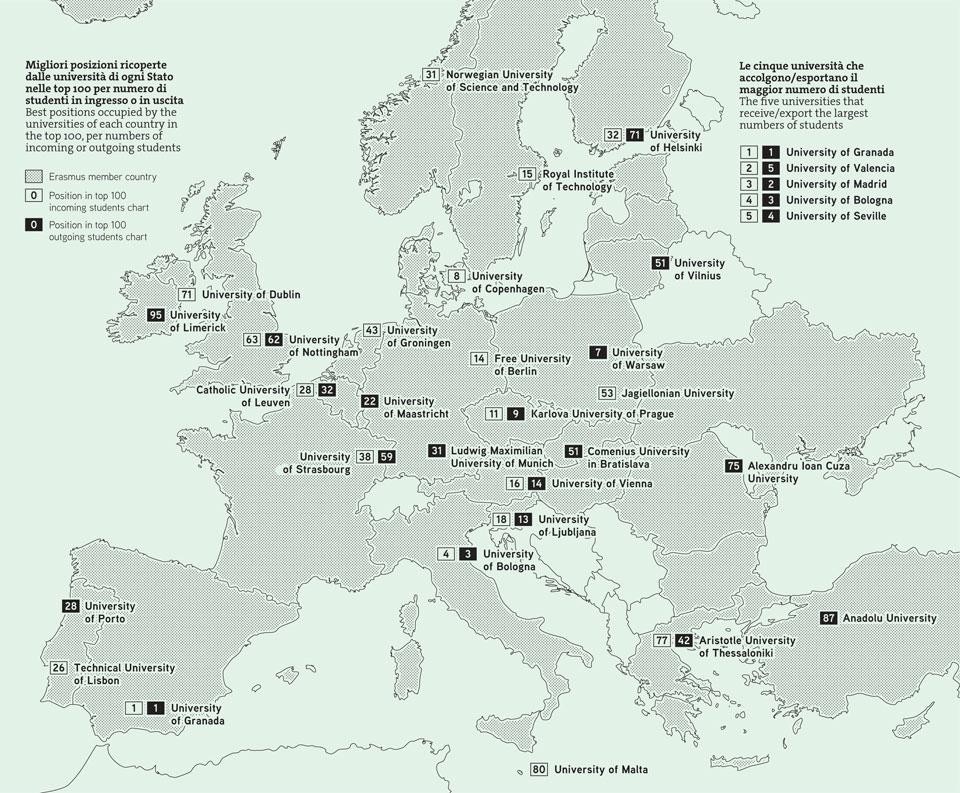

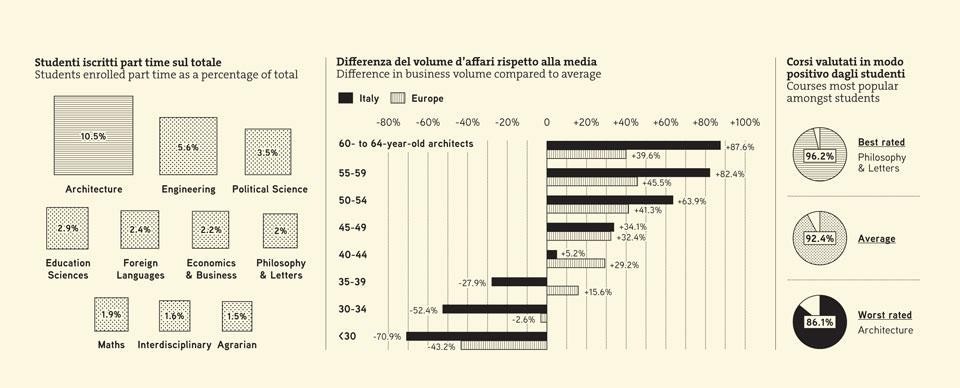

I doubt that anyone would be shocked if I ventured to say that for more than a few decades, architecture training at university level in Italy has been going through a phase of profound crisis. Even if we decide not to place blind trust in international rankings — which in any case tend to be rather stingy when it comes to Italian universities overall, generally including only Bologna and La Sapienza among the world's top 200 — there must be a reason why even the architecture schools with glorious pasts cannot considered competitive on a global scale. Maybe the problem is twofold, tradition versus the global scale.

The importance attached to architectural “theory” in Italy finds no outlet in practical matters

Here we come up against the problem of tradition. Much to our chagrin, it is an annoyingly recurrent cultural issue in Italy, a country that is continuously short of breath from chasing its lost architectural identity. Much as we would like to pretend otherwise education is still mainly shackled to the golden age of Samonà, Rogers and Quaroni — in other words, the days when Italy was indeed exporting method and culture. Tragic as it is, we have to admit that even after four successive generations of faculty members, the long-awaited reference-frame of research is still all too often the same. What has taken place in the meantime to prevent any form of evolution?

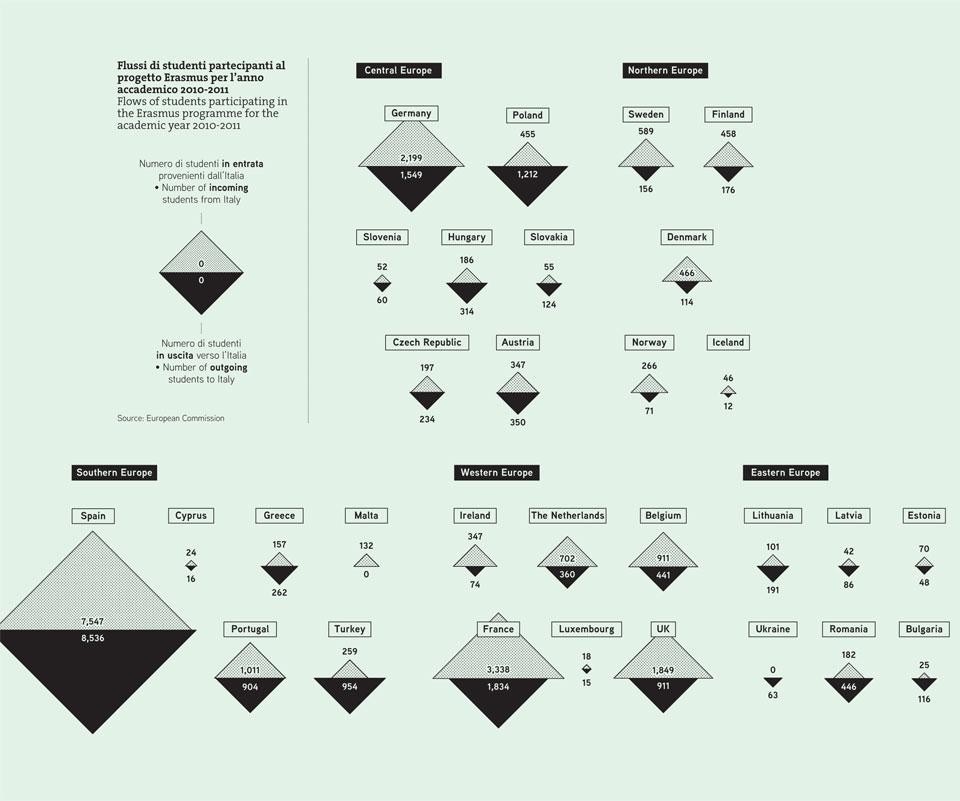

Even if we assume that intervention in the system is the best way to resolve problems related to a nation's academic culture, in architecture this could only be translated into policies for the built environment, namely the creation of a socio- economic condition that is ready to welcome new incoming professionals. This was the case in Spain (at what turned out to be an extremely high cost) when it turned its attention to design towards public space, an ideal training ground for young architects. It is pointless to continue tweaking legislation in order to alter the formal aspects of university regulations without ever profoundly renewing the content in accordance with a socioeconomic condition that is completely different than the one in which the old institutions were founded.

Of course, it has always been the case that the most interesting research originates in independent research groups that form within the very same institutions whose deficiencies they intend to expose. But we cannot be satisfied with the fact that this is the only added value these unrelated and pulverised movements are able to confer to our institutions — and only after immense effort, ludicrous financing and minimal recognition. At most, our universities can only muster the image of elephantine diploma factories whose products, in a certain sense, have questionable value today.