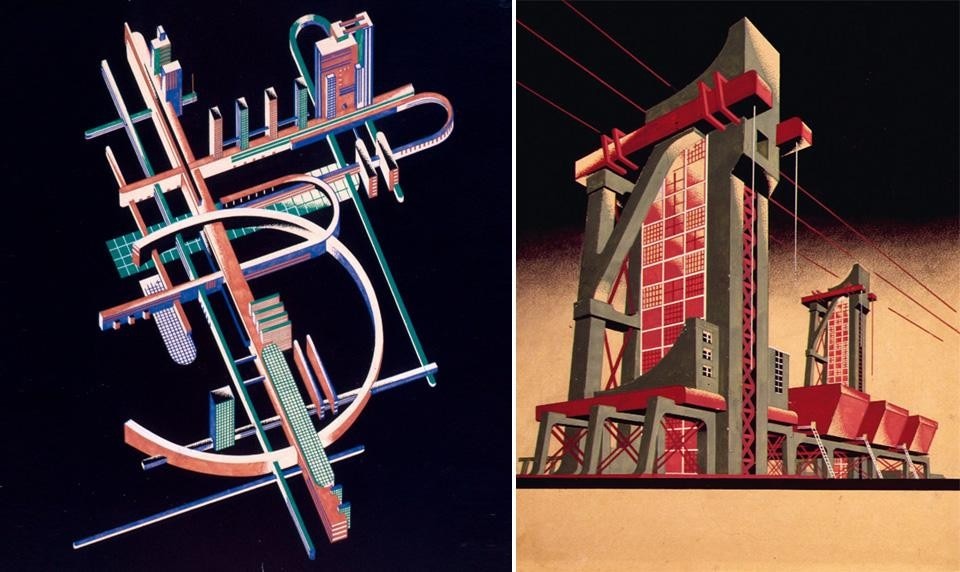

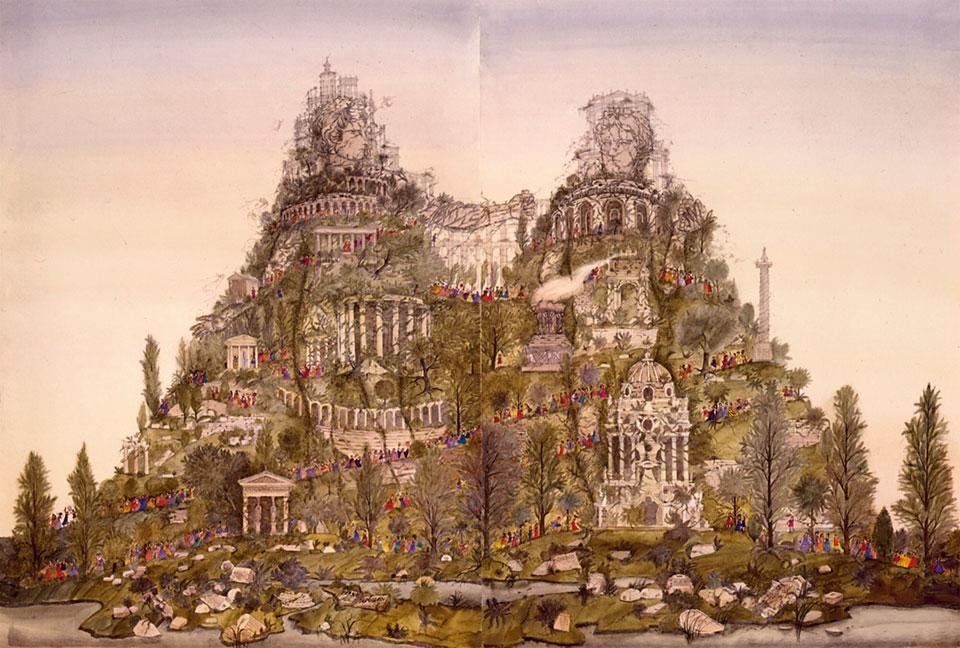

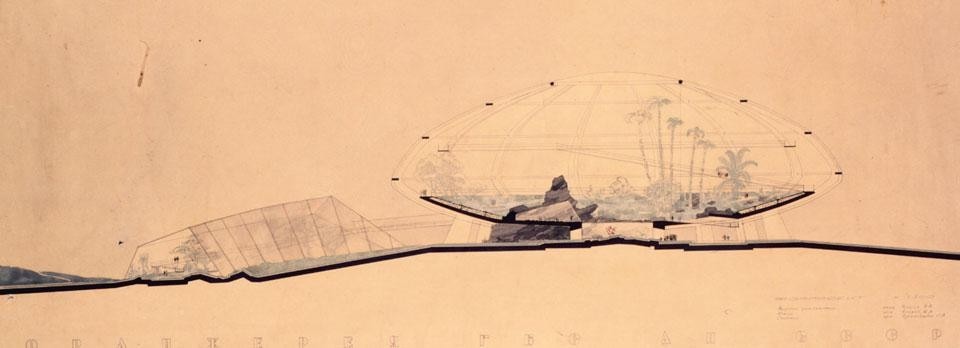

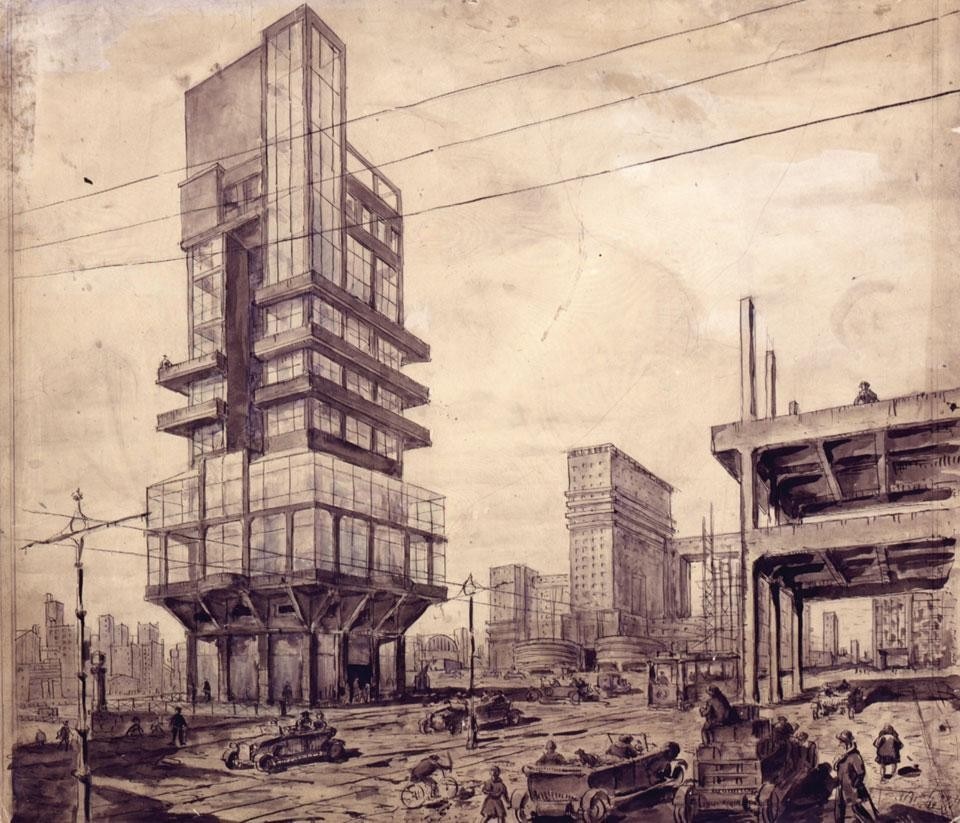

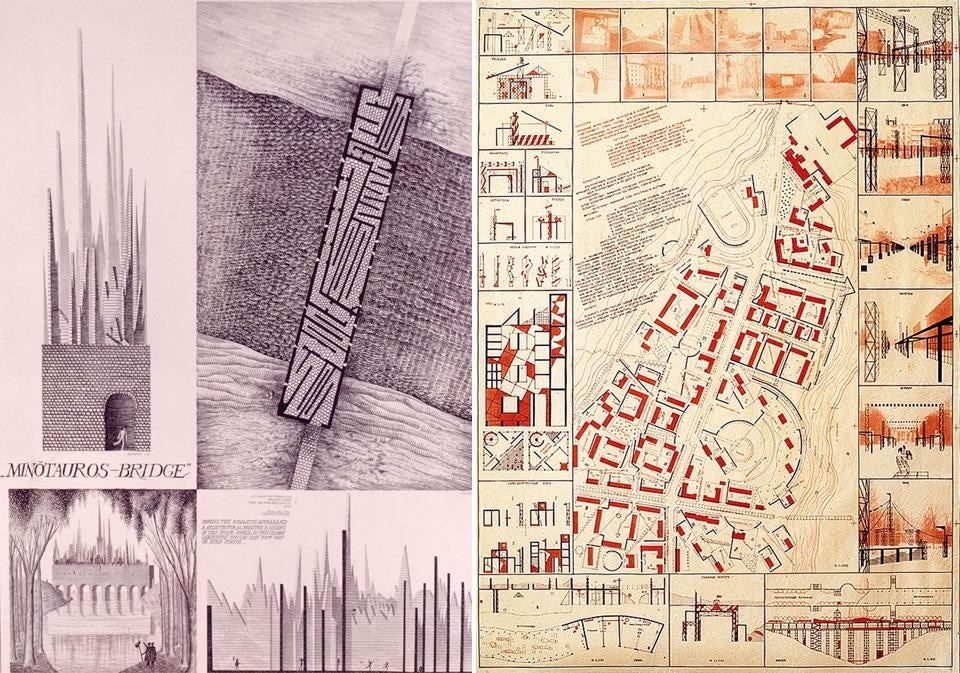

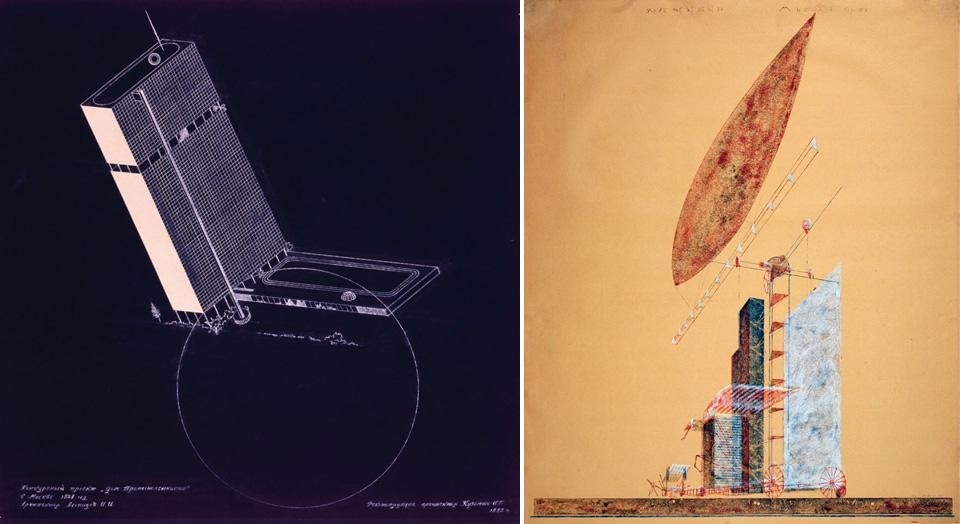

Closer to the sensitivities of artists than to the demands of architecture, the paper architects pictured a dreamy world and an oneiric architecture. Often fomented by the frustration of working at the central office of State architecture, the paper architects practiced an idea of architecture in which projects dissolved into surreal atmospheres. Their paper architecture was a way of cultivating the eccentric and the individual, in a culture which at least officially—and long before perestroika—was still founded on the ideology of standardisation. In this sense, paper architecture was also intimately associated with the non¬conformist practices of Russian art in the 1980s. It was an architecture that made a virtue out of necessity, by transforming the impossibility of realisation into a stimulus to create new fantastic worlds.

Their household gods were Piranesi and Ledoux, Russian Art Nouveau and constructivism, about which in the 1920s the expression "paper architecture" had been coined for the first time, and disparagingly.

...When we mean to build

We first survey the plot, then draw the model

and when we see the figure of the house,

then we must rate the cost of the erection;

which if we find outweighs ability,

what do we then but draw anew the model

in fewer offices, or at last desist

to build at all...

William Shakespeare, Henry IV, Act I, 3

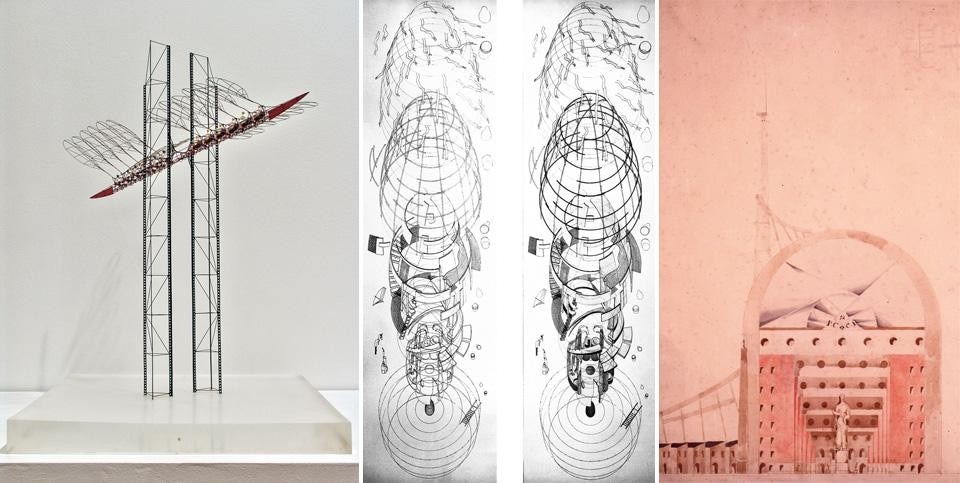

The art shown in this collection holds a special place in the contemporary artistic process. The term "Paper Architecture" was assumed in the 1980s as a working name by the founders of the "Paper Architecture" movement, a group of young Moscow architects.

Historically, paper architecture was a derogatory term in Soviet Russia: in the 1930s, the opponents of architectural "group rivalries" of the "Golden Decade" so referred, derisively, to avant-garde architects/artists of the 1920s. Ever after, everything that transgressed the limits of normative architecture tended to be lumped, by officials, under that general title. Mindful of the idealistic Utopianism of their predecessors who were frowned up, even persecuted by society, the new "Paper Architecture" declared, in its formative period, that it gave up, in principle, any applied tasks in favor of pure architectural/artistic concepts. One cannot construct from paper designs. They are certainly no blueprints for the building industry: rather, these are "projects of projects".

Paper architecture set out precisely to free poetry, by dissociating the project from its execution. For us it was important to concentrate on presentation and representation, on the concept and not on the end result

In the 1980s, "paper Architecture" was a result of what seemed to be the hopelessly inescapable stagnation in life, architecture and the building industry in the Soviet Union, from which international competitions of architectural concepts were a welcome escape. The first victory at one of the Japanese-sponsored competitions of architectural ideas came in 1981; it was followed in 1984 by the first exhibit of "Paper Architecture" in Moscow held at the editorial offices of a youth magazine); the first significant publication appeared in 1985; and the first show abroad was arranged in 1986.

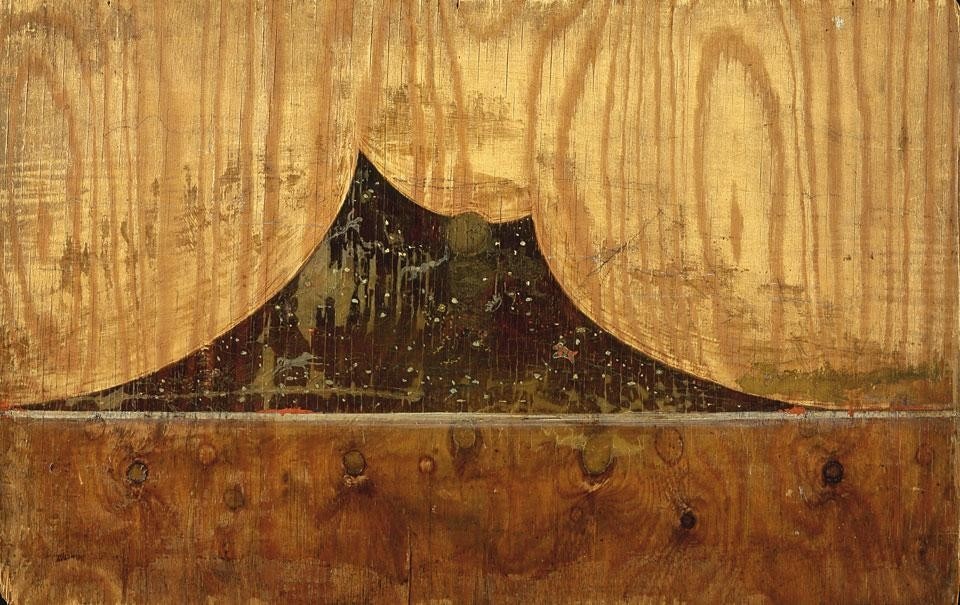

The evolution of "Paper Architecture" is unusual and instructive: it moved from the semantics of architectural ideas toward the expressionism of the easel painting, from the figure of an architect toward that of an artist, from the ideology of an artistic group to a highly individualized position of its every member. One should no think, however, that this "from — toward" motion implied the rejection of the former and the affirmation of the latter. No this new art proved to be wise enough to wed the experience of the past to present-day knowledge. The word "Paper" is no longer an obligatory component of that world combination, whereas "Architecture" denotes rather the professional and educational status of those who produce it and is present in the design concepts which make up the core of mos of such works. With time, the stylistic definition of many works became more compressed. A sketchy rather than detailed program of visual, literary, philosophical and conceptual intentions of every "Paper Architect" could be perceived in a variety of contexts. Guesswork as to the true contents of a "project" served not so must to decipher them as to add new meanings which came in line with the vector of the artist's design concept.

Mere sheets of paper — watercolors, drawings, etchings and serigraphs — shown in this collection are, on the one hand, works of art in their own right and, on the other, accumulations of design energies aiming to expand future spaces. While these people build nothing, they do construct a little something. Yuri Avvakumov, Georgy Nikich