Architecture, like history, materialises through stratification. In September 1944, bombardments destroy an ancient hilltop chapel at Bourlémont, near Ronchamp, whose origins date back to the Middle Ages. The town's inhabitants appeal for its reconstruction. Le Corbusier is entrusted with the design of the new chapel, and Notre-Dame du Haut is consecrated on 25 June 1955. Fifty years pass, and the local religious authorities, spurred on by the decision to transfer the residence of a small group of nuns to the site, decide to renovate and extend the existing facilities. Renzo Piano, it is announced, will design the new expansion.

The decision to intervene so drastically on the site of one of the sanctuaries of late modernism instantly sparks off a heated debate. Two apparently irreconcilable forces clash on the hilltop of Bourlémont: on the one hand, the religious community's understandable desire to update the management and hospitality facilities of an active place of worship; on the other, following the justified logic that the site constituted an integral part of Le Corbusier's design, the impulse to extend the mantle of preservation beyond the architectural artefact itself to encompass the entire site, even at the expense of its continued vitality. The two texts that follow, written by Fulvio Irace and Jean-Louis Cohen, outline differing perspectives on the matter.

by Fulvio Irace

Oportet ut scandala eveniant ("A scandal can be a good thing"). This Latin saying may well be the most appropriate reply to the huge controversy produced by Renzo Piano's recent work on the Bourlémont Hill, at the foot of the chapel at Ronchamp. The "scandal"—indeed, out-and-out "murder before the cathedral" according to the project's most resolute opponents— is to have built a tiny convent for the Poor Clares and a new visitor centre "too" close to Corbu's work, significantly altering the approach to the place of prayer conceived by the master as the end point of a slow and laborious arrival process.

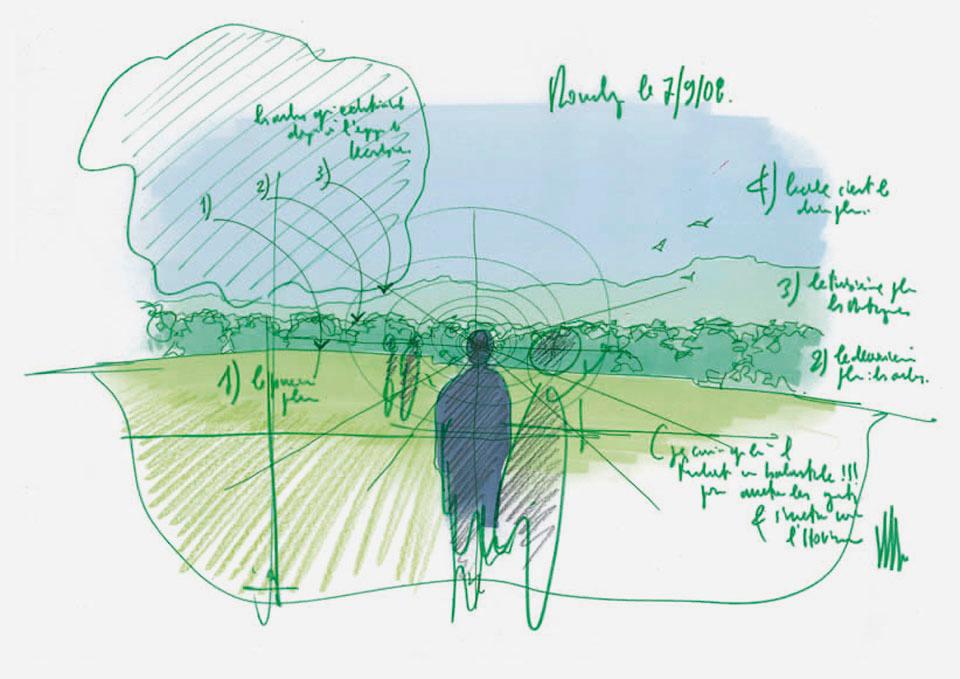

Basically, it was envisaged as a lay ascension to gain access to the "beatitudes" of a "sermon on the mount" in which the devotee's religious awe is partly fuelled by the sounds of nature ("acoustic architecture", according to Corbu), the true and mighty interlocutor of the sculptural explosion that dominates the peak. "I spent three hours on the hill," he said, "getting to know the ground and the horizons. Allowing them to pervade me." Everything at Ronchamp is sacred in the inexpressible manner of the revelation. Even years after its construction, the fear of seeing it turned into "a new Lourdes" forced Le Corbusier to write angry letters to Abbot Bolle-Rédat saying that nothing was to be changed over the years and the original view of the valley was to remain unaltered.

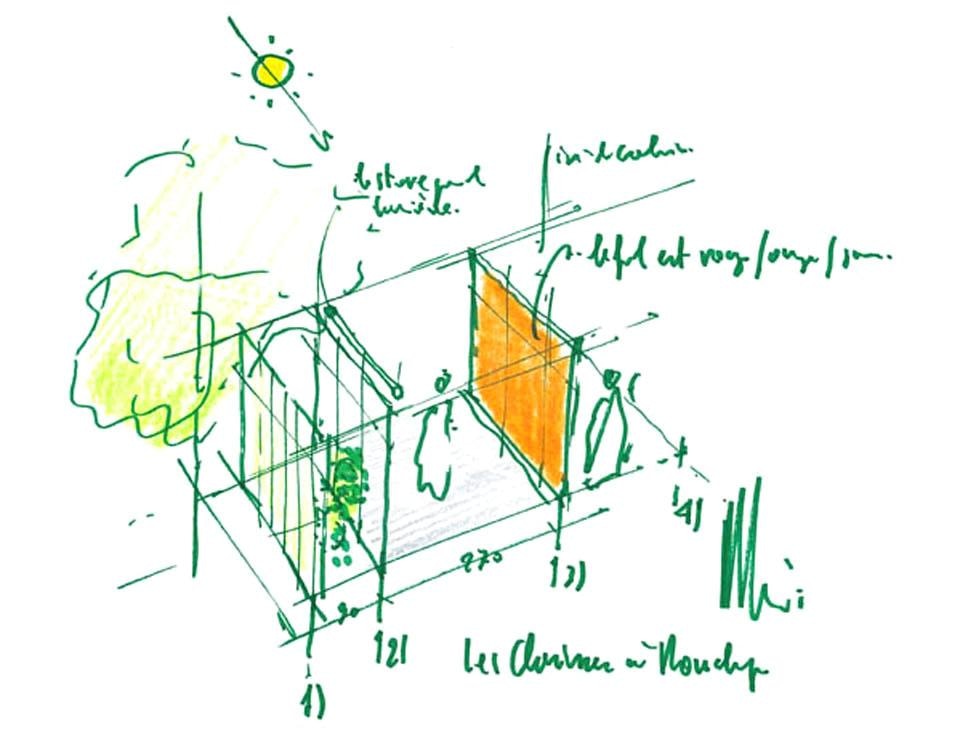

Now that the work is almost complete, we must follow Galileo's example and invite the accusers to look through the telescope. Actually, the whole issue appears overblown even to the bare eye, as ascertained by the hundreds of pilgrims who climbed the hill for religious services on 8 September, the anniversary of the Virgin Mary's birth. Piano bowed to Corbu's noli me tangere and withdrew to the foot of the hill and a position well away from the millenary pilgrims' path that does not interfere with the gradual climb to the chapel from the foot to the top of the hill. The Poor Clares have installed themselves like worker bees in a handful of tiny beehives (2.70 x 2.70 metres) clinging close to the hillside. Crouching in the half-light of the undergrowth, the cells are a low-key countermelody to the mighty voice of the chapel, a rural community of forest inhabitants who practise their vision of religion as service and prayer. These minimal unité d'abitation could almost have been designed by Prouvé, a perfect assembly of modular elements and "ordinary" materials—zinc roofing, slender steel sections, concrete wall panels and wooden furnishings—that communicates the Franciscan graciousness of work that is done well, humble and precious.

Design is a negotiation that can be improved upon with fiery but not hostile interlocutors. —Fulvio Irace At Ronchamp, the “sphere” of design indivisibly associates architecture with landscape.—Jean-Louis Cohen

Yet, if people would set aside their suspicions and preconceptions, Piano's output could be analysed as an organic succession of fine works, silent masterpieces and even routine products. He would be seen as a member of a trade—that of the architect—that only achieves the tone of an epic novel when reconstructing monumental history, when every "action" must express an epochal "must be". Piano reminds us that no problem can be addressed (and perhaps resolved) except via minute analysis, not starting from the outside but observing it from inside.

At Ronchamp, the issue is not the comparison with Le Corbusier, which remains a fact and not a point of parallel. The issue is how we govern the metamorphoses that affect society and cultural change. The chapel is no longer the solitary pilgrimage of 50 years ago because its charisma as a work of art has changed the way it is perceived and altered visitor expectations. Claiming that people can climb the hill now as Le Corbusier did in June 1950 is naive as well as untrue. But this is where we gauge the usefulness or harm of the project for life: by trying to create a balance that respects the place but also its new uses, so as to prevent Ronchamp ending up the "madhouse" Corbu so feared.

Fulvio Irace

by Jean-Louis Cohen

Four years after Renzo Piano's presentation of his Ronchamp project, the situation could not be clearer. Transformed in its architecture since the original concept of 2007, the work is now all but finished. In response to the inescapable reality of the completed buildings, the reflections inspired by the initial idea studied by the architect of the Centre Pompidou have still to be made available.

This means going back to the actual sources of Le Corbusier's project for the Chapel of Notre-Dame du Haut and its site, and superseding the collages of docked quotations sometimes used in the heat of controversy. What exploded in 2007 and 2008 was indeed a controversy, marked primarily by the drafting of two petitions, one in defence of "creative freedom", the other aimed to safeguard the Ronchamp site and contesting the project's innocuousness.[1] The discussion culminated in a debate organised at the Cité de l'architecture et du patrimoine in Paris on 25 June 2008, during which the arguments put forward by the two sides were debated.[2] The critics and opponents had no intention of obstructing the initiative undertaken by the OEuvre Notre-Dame du Haut Association that commissioned Renzo Piano's project, whose creative impact they unanimously admire. Their purpose was completely different.

Attentive to a strict interpretation of Le Corbusier's original intentions and of his recurrent statements on how to use and manage the site and its complex, the reactions—contained in the book—are not confined to a purely negative vision of the site's potentialities, which would have prevented any new construction anywhere on it. What was disputed was the location chosen for the Clarisse Convent project, very close in fact to the chapel, despite the somewhat flattering sections in circulation, rather than the principle of a convent. Nor was the deplorable construction of the pre-existent entrance defended by anybody, even though the volume intended to substitute it in the initial project was considered excessive. Furthermore, there was no lack of public land in the vicinity, and aid from the Haute-Saône Regional Council could have helped to make such sites available.

We have acknowledged the alterations that arose from the discussion, but at the same time it is important to resume the motivations and lines of argument presented by those who insisted on regarding the operation as out of place. Out of place in the strict sense of that expression, since it penetrates into what might be defined, to paraphrase Edward T. Hall, the "sphere" typical of Le Corbusier's architecture, which at Ronchamp indivisibly, as in many other places, associates architecture with landscape. If there is something to be learnt from this episode, whose traces on the land will be lasting, it is precisely the importance of Le Corbusier's works being rooted in the natural scenery, and the urgent need for an informed, documented reflection on every dimension of the works to be protected.

Jean-Louis Cohen

NOTES:

1. Grégoire Allix, La bataille de Ronchamp, in Le Monde, 20 May 2008.

2. Renzo Piano, Ecco le mie ragioni, in Il giornale dell'architettura, n. 63, June 2008, p. 5.

3. Manière de penser Ronchamp, Paris, Fondation Le Corbusier, Éditions de La Villette, 2011 (contributions by Jean-Louis Cohen, Jean-Pierre Duport, Michel W. Kagan, Josep Quetglas, Gilles Ragot, Nathalie Régnier-Kagan, Bruno Reichlin, Stanislaus von Moos).

Client: Association Œuvre Notre-Dame du Haut + Poor Clares (Association Sainte Colette)

Landscape: Atelier Corajoud

Consultants: Sletec Ingénierie, M. Harlé, C.Guinaudeau, P.Gillmann, Nunc/L.Piccon

Monastery area: 1700 m²

Gatehouse area: 450 m²

Roofed area: 1386 m² (convent: 263 m²; Poor Clares' living area: 296 m²; workshops: 120 m²; oratory: 260 m²; guest quarters: 443 m²)

Budget: 9.000.000 € including landscaping and site rehabilitation

Do you know how a food disposer works?

60% of American kitchens have one, and food waste disposers are becoming increasingly popular in Italy as well. But what exactly are they, and how do they work?