Numerous legends are in circulation concerning Toni “el Suizo” (Swiss Tony), and they are precipitated by the existence of the Internet. Although he is labelled an engineer, Toni Ruttimann considers himself just a self-taught bridge builder. When he finished high school in 1987, Ruttimann was shocked by the devastation caused by an earthquake in Ecuador where he was working as a volunteer. He left the university where he had been studying engineering for just six months to return to Latin America and commence unceasing community work aimed at building bridges. In a Borges-like multiplication of mythical stories, other versions that circulate on the Internet refer to the impression made by the flooding caused by El Niño (the cyclical meteorological phenomenon that affects the equatorial Pacific) as the reason behind Toni’s public-spirited vocation. Ruttimann has refined and perfected a construction method learnt from oil rig engineers that is conceived to be built by hand, where choreographing the movements and actions necessary for moving and building the structures is essential in the design phase.

The role that Toni el Suizo has carved out for himself is one of supplying technical support in bridge building, while also managing to engage the energy and enthusiasm of the community of citizens with whom he works. Ruttimann roams incessantly in search of places where necessity is latent, carrying out a far-reaching activity of persuasion and public involvement. The tangible end result is a source of pride and rediscovered dignity for those who have done the building work, compensating for the slowness and inefficiency of the institutions. It implies a potential subversion of the power distribution mechanisms and democratic participation. Passing through changes made to the territory itself, first hand, is a latent political vindication for a visibility and presence often denied.

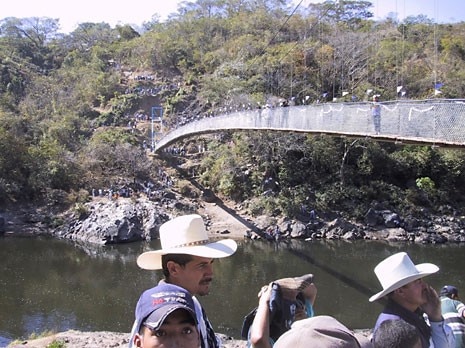

The pedestrian bridges are suspended structures, analogous to those built for the flow of hydrocarbons: two towers in welded metal tube erected on the two opposite banks support chains made from steel cable, to which are hooked wooden boards cut by the inhabitants on site. The material is constituted by segments of steel pipe retrieved from industry, transported in lorries and moved manually by the inhabitants. Over recent years steel cable has been supplied by Swiss cableway companies, steel tubing by the multinational Tenaris, controlled by Techint, and free transport by the maritime company MSC of Geneva. The welding is done by Ruttimann’s assistants and fixed to the concrete foundations that have been built by members of the community involved, who offer their services on a voluntary basis. Each bridge costs approximately 500 dollars in materials and transport provided by Ruttimann and the organisations that support him; a further 500 dollars for timber and concrete is supplied by the communities themselves. There is no cost for the design and manpower. The average length of each bridge is between 50 and 100 metres. The bridge that crosses the Aguarico River in the north of Ecuador spans 264 metres, a successful combination of low-cost technology and hand-crafted sophistication.

The interventions carried out, such as the bridge over the Lempa River that separates Honduras from Salvador, trigger small-scale economic development processes that are managed from below. Mapulaca en Honduras and Victoria en Salvador have been connected by the Puente del Amor (as the citizens have named it), which was built without any help from institutions. These two places constitute the seed of a collective system that transcends the national segmentations imposed on the indigenous communities. Guillain Barré syndrome, an illness contracted by Ruttimann in Cambodia in 2002 that attacks the nervous system and significantly reduces the body’s motor capacity, has not stopped him doing all he can. Toni has developed a piece of software which, after entering data, gives precise indications regarding the size of the elements, how to cut them and the kind of welding for the connections. Walter Yanez (an Amazonian welder) and Yin Sopul (a Cambodian mechanic) have been working with Toni for many years and translate the designs that can no longer be developed first hand.

Over 230 bridges (other sources quote 160 or 324), located mostly in rural communities, have been built with crucial help from Toni, as he is affectionately known to the people he has worked with. Consider that over 600,000 people in Ecuador, Colombia, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Mexico, Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia have seen the quality of their everyday lives change thanks to the building of connections that cross ravines, rivers and torrents, making it easier and quicker to move around the areas where they are located.