<

I had wanted to see the house in sunshine. When I left Milan it was one of those perfect early autumn days, with a deep blue sky and the soft golden light of a low sun. But by the time the Lufthansa flight lands on the tarmac, the cloud is leaching away every scrap of colour. On the autobahn the rain slows traffic to a crawl and the afternoon turns gradually murkier, making everything look flatter and flatter.

When you are looking for a particular piece of architecture in unfamiliar territory, inevitably you scan every passing flat roof and every large window, waiting for that jolt of recognition that comes the first time you see a project that you know well from drawings and models turned into physical reality. It’s that mixture of the familiar and the startling that comes when a celebrity walks into a restaurant. You know what they look like, but you don’t know that really is what they look like. It’s almost dark before we finally reach the house.

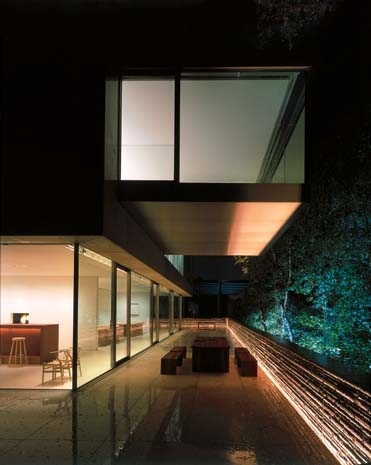

The tree-lined road on the suburban fringe of a small town is marked by the villas that defined Germany’s post-war prosperity. Set a little way back from the curb, a low band of warm artificial light, framed by a band of stone and screened by timber strips, signals the house’s presence with quiet authority. The sunshine, as it turns out, isn’t necessary.

The house is unmistakable, and surprisingly vulnerable in the dark. The drizzle has turned to rain now, and the group of figures clustered around the camera tripod are sheltering under umbrellas. Two assistants are trying to unpeel the last traces of the construction fence that has not quite been cleared away and struggling to get the builder’s not very portable site toilet out of shot. The architect, John Pawson, is getting a little wet while the assistant holding the umbrella concentrates on keeping the camera dry.

Inside, two figures are visible through the glass. They are the clients; coming out to greet another visitor to the house in which they have still not quite finished unpacking the last boxes of books. These are conditions in which most architectural photographers would down cameras immediately and return to their hotel to wait for a break in the clouds. But the photographers work on.

It is, on one level, the most artificial of scenes. An image is being constructed that will have a life of its own, becoming part of the currency of architectural discourse that will often be conducted in an abstract sense, entirely divorced from the life of the house and this wet October evening. But it doesn’t feel quite like this. I am introduced and taken inside.

What can it be like to have our house photographed by complete strangers, ushering visitors around who take an intimate interest in the contents of every cupboard, the specification of every hinge and the provenance of every piece of furniture? Who play with the digitally controlled light system and the taps and blinds? And who stand with that art gallery slant of the head for minutes at a time regarding a bedroom as if it were an installation? But there is something about this particular house and its presence that transforms the situation.

The house allows everybody in it the space to breathe. It is like walking into a decompression chamber. The flight, the autobahn, the rain, the potential awkwardness of a disparate group of people here for disparate purposes melts away. It doesn’t feel like voyeurism. It doesn’t, I hope, feel like an imposition. What is left is a house – a place for a family to live, in which to feel comfortable. It’s a house that has been designed to make every transaction in it – having a bath, boiling an egg, leaning over the kitchen table and talking, sitting on the sofa looking at a book – feel as if it is a worthwhile way to spend time.

And photographing the house is no different from the other rituals, both arcane and everyday, that can take place in the life of a house. John Pawson has been designing houses for 20 years. Each is entirely different, but all are about the same things. At heart they are about a relationship with a particular place, about creating an environment for a way of life.

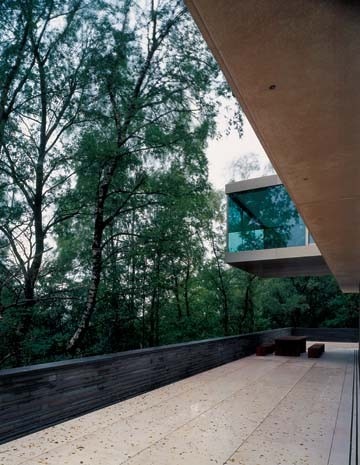

The architecture is there to remind us of some of the things that we know matter but may have forgotten to notice. Sunshine on a wall, drinking a glass of wine while looking at a fire, noticing the different shades of white on the wall – it’s an exploration of tactile, visual and emotional qualities. And the architecture of the house is there to heighten them. This is a house that stands on the edge of a slope so steep and so thickly wooded that most of it can’t be built on. It’s a situation familiar to architects, from Mies van der Rohe in Brno to John Lautner in California. There are different approaches to dealing with it. You can cancel out the effect of the slope through the construction of a podium, through excavation or by setting the structure on stilts.

For this house, Pawson’s design is single storey toward the street entrance, but it steps down the slope to create a second floor at the back of the house. The other big decision was to put the main staircase parallel to the front – that is, the long elevation of the house. From these two decisions flows most of the planning of the house. The bedrooms are on the upper level, a placement gives them the sense of being in the trees that surround the house.

The living room and kitchen are on the lower level, with a direct link to the outside south-facing terrace and the garden beyond. The plan is designed for the house to give parents and children their own spaces within the house. The parent’s bedroom is at one end, and the children are at the other, with their own small kitchen and what now serves as a playroom and will become a secondary living room as they grow. A spacious spa room is the buffer between the two wings of the house. The master bedroom cantilevers out into the trees with floor-to-ceiling glass on three sides.

At the heart of the house is a double staircase with a skylight above that creates a powerful sense of tension, pulling light and space through a ravine-like space that slices through the whole house. On the lower floor the two descending flights meet on an elevated platform that opens south into the dining room and north into the strip of cloakrooms and service spaces that run along the windowless north wall of the house. Guests don’t see the kitchen to the right unless they are guided in.

The more formal living room is to the left, with one space opening into the next along the length of the terrace. Pawson likes simplicity, and this is a house that is informed by it. But there is more in this project’s use of materials than could be deduced from his previous work. He uses discreet, robust materials, rough stone and granite, on the lower level. The interiors have stone floors with a red sandstone table in the kitchen and a dark timber screen on the stairs. In the end, it’s not the materials but the way they are used that makes this such a serene space.

There is a duality in Pawson’s work: he speaks of the physical experience of moving from one space to another, of feeling the sense of compression of passing through the thickness of a wall. And this house is about many such dualities. The solidity of the stone base set against the apparent weightlessness of the floating cantilevered bedroom. The mass of the walls, with the ambiguity of the veiled reflections on the glass. The sense of reassurance that comes from the comfort of enclosure, contrasted with the exhilaration of the open landscape glimpsed through the bare trees in winter.