The European avant-gardes of the 1920s, eager to revolutionize making and thinking for the modern world, yet lacking the means to test their ideas in practice, presented their work in numerous small but influential international journals. Contemporaneous with better-known periodicals such as De Stijl and L'esprit nouveau was the Berlin-based journal G: Materialen zur Elementaren Gestaltung [G: Materials for Elemental Form-Creation], which until now had been all but forgotten. A new volume edited by the late Detlef Mertins and Michael W. Jennings, two distinguished scholars of Weimar-era culture, restores G to international circulation while arguing for its historical importance as channel of avant-garde discourse.

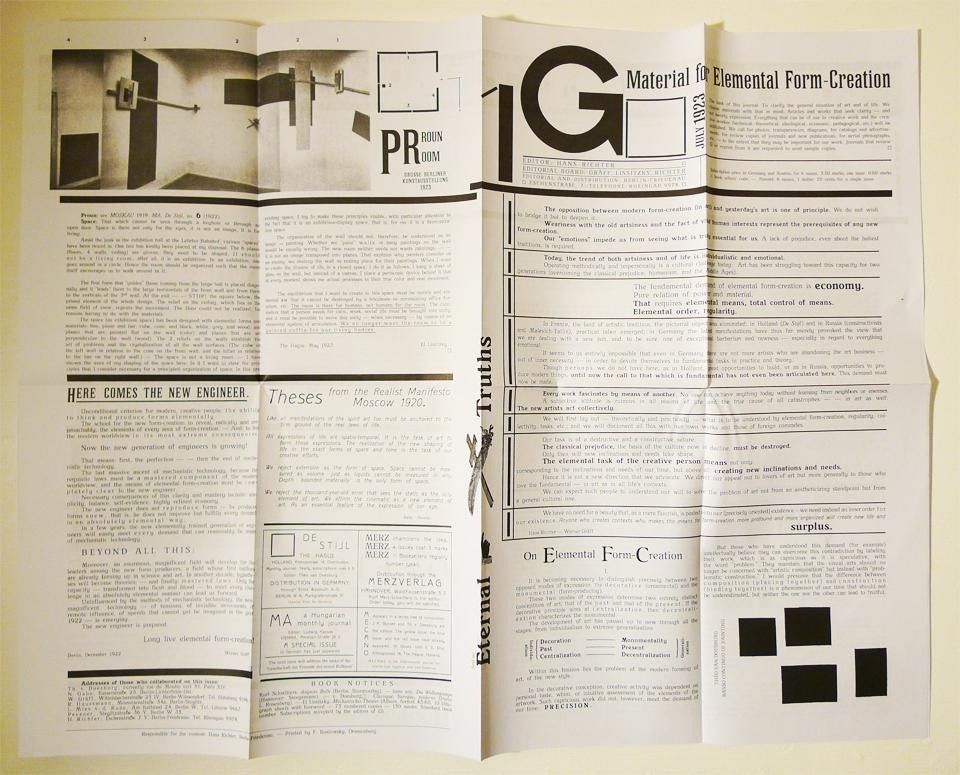

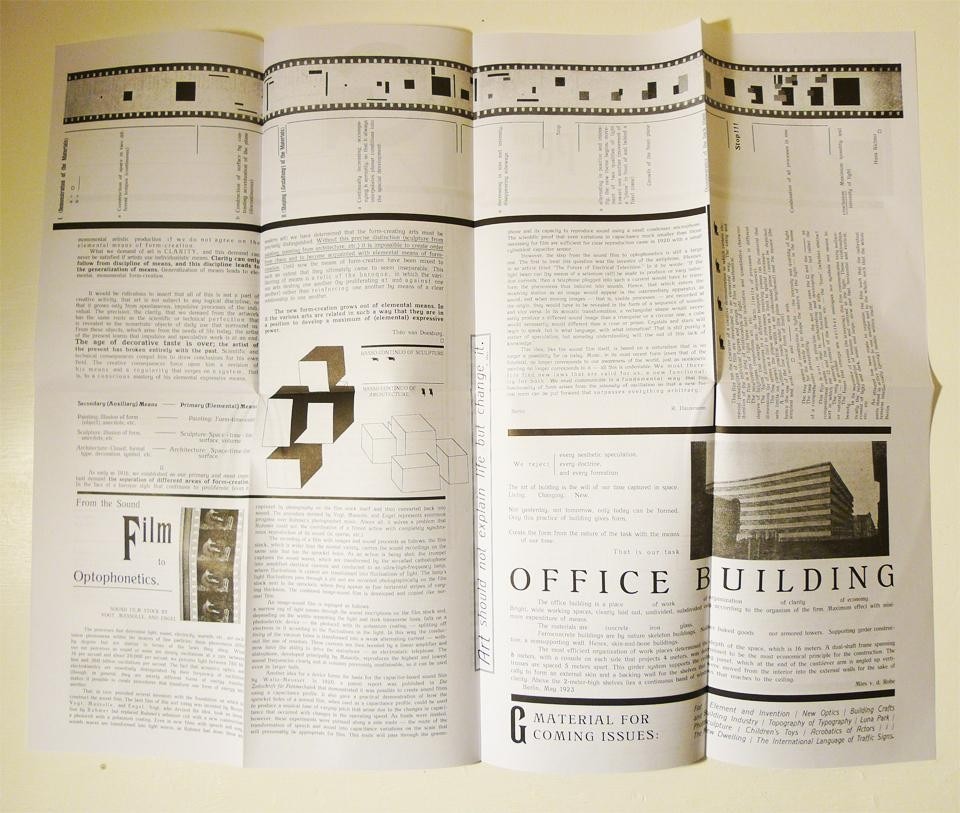

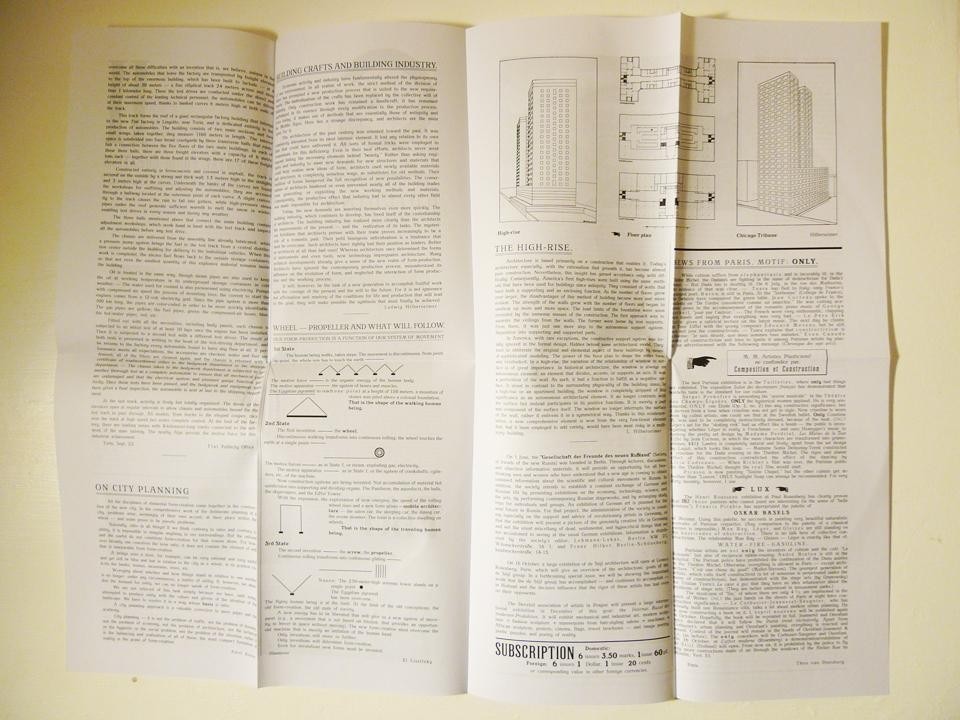

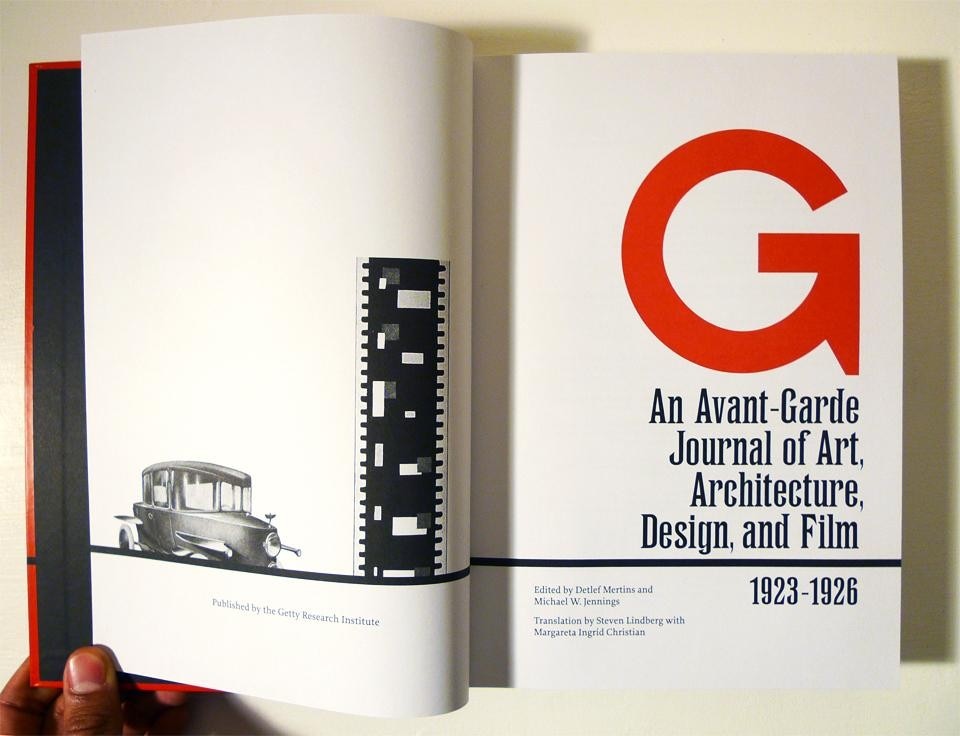

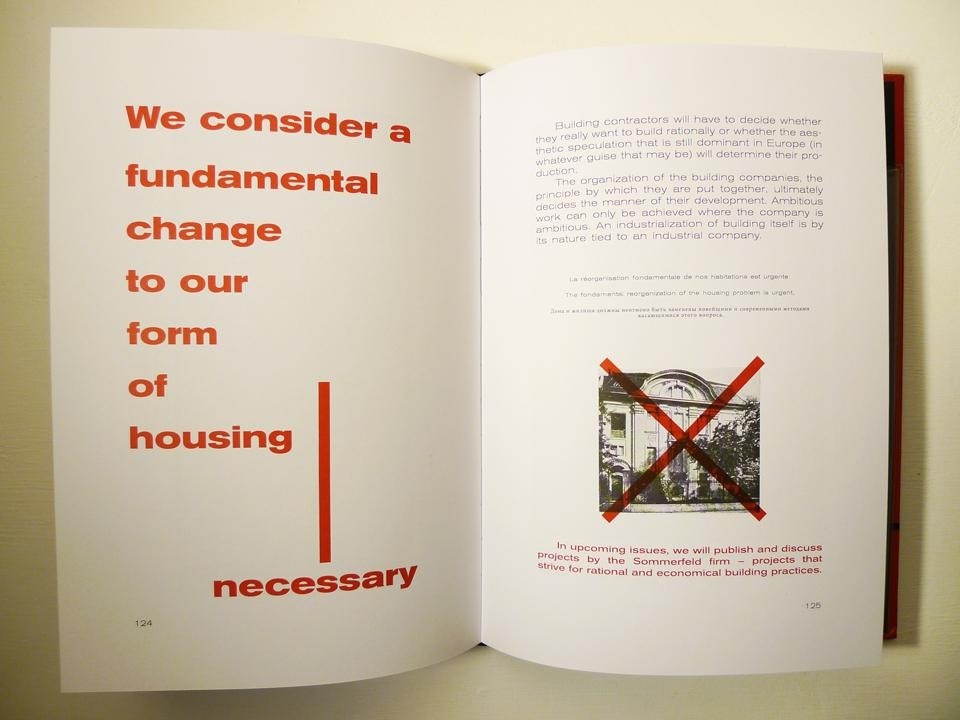

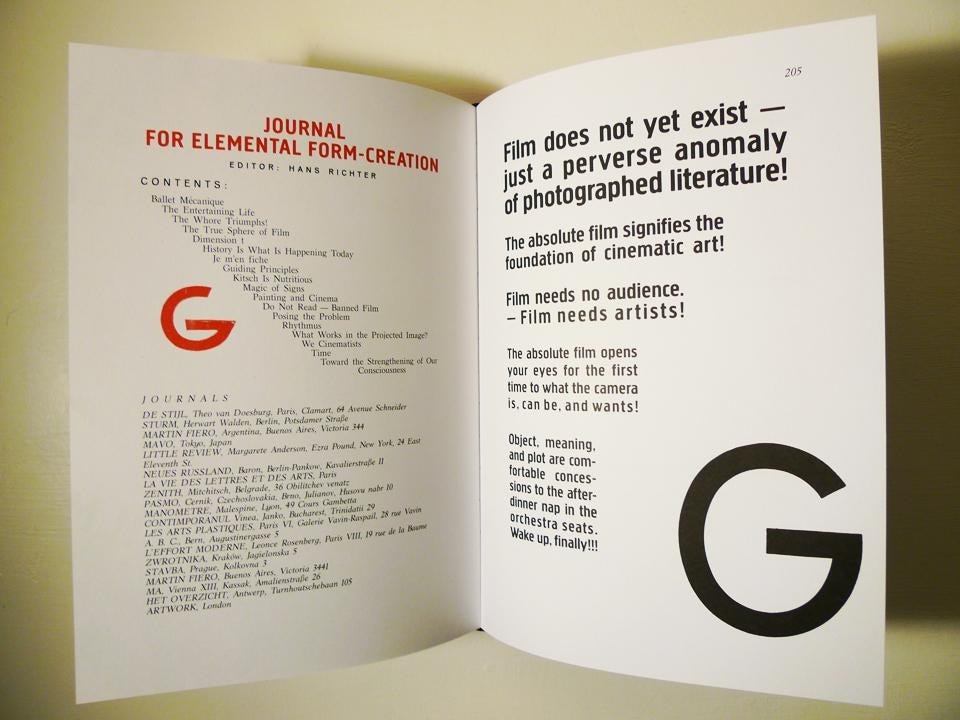

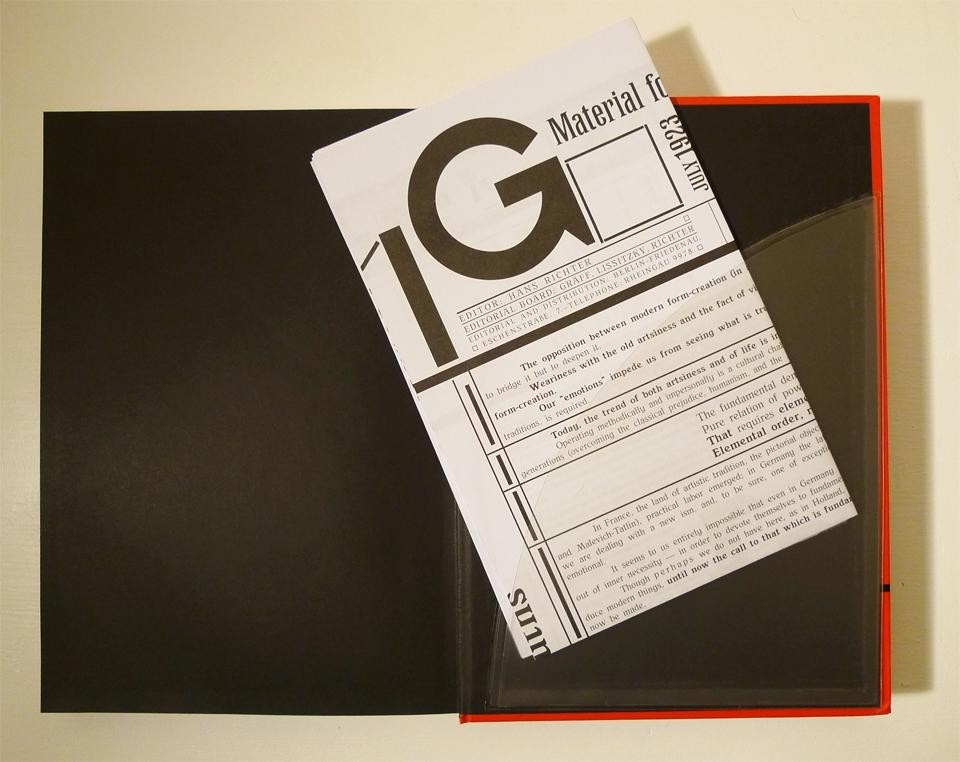

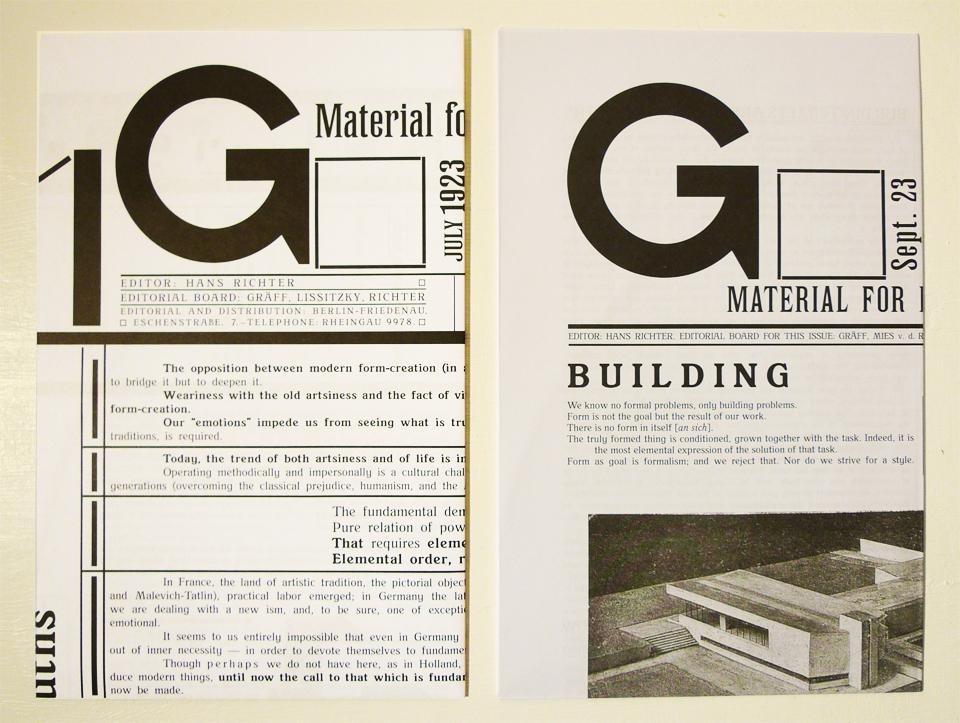

G: An Avant-Garde Journal of Art, Architecture, Design, and Film, 1923–1926 binds three interdependent projects in one bright-red volume. It is simultaneously a meticulous restoration, a modern translation, and a critical history. If today's readers are to appreciate G as "one of the earliest journals of modern visual culture," as Edward Dimendberg suggests, then we must have access to its look and feel as well as to its content. And to our great satisfaction, we do. Through exacting graphic and typographical reconstruction executed by Chris Rowat Design, the newly translated text is presented to the English-language reader much as it originally appeared in German, including long-lost typefaces and intricate layouts. The first two issues are faithfully reproduced in the form of fold-out tabloids tucked inside the book's back cover. The editors exercised restraint in not attempting to correct or annotate the errors and inconsistencies in the original, allowing the reader to encounter these problems directly. Instead, the critical force is centered in the scholarly essays by Mertins, Jennings, Dimendberg, and Maria Gough, plus a foreword from Barry Bergdoll, which interrogate G while illuminating its place and time.

The ruins of the old order, still smoldering from the cataclysm of the Great War, seemed to demand new approaches to all aspects of life. In an atmosphere aflame with constant transformation and debate, multiple futures beckoned like factory-fresh airplanes ready to fly in different directions.

In its dual character as a primary and secondary resource, together with its readiness to segue into present-day debates on visual culture, the new G provides the reader with uncommonly rich means to actively engage with an historic document. Indeed it comes about as close as a scholarly resource can come to achieving the "two-way" communication that Maria Gough ascribes to the pioneering work of Bertolt Brecht and El Lissitzky.

Gideon Fink Shapiro is a doctoral student in architecture at PennDesign, the University of Pennsylvania. His writing has appeared in DomusWeb, Architect Magazine, Abitare, Crit, Gothamist, and Streetsblog.