"In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it."

Jorge Luis Borges, Collected Fictions, Translated by Andrew Hurley Copyright Penguin 1999

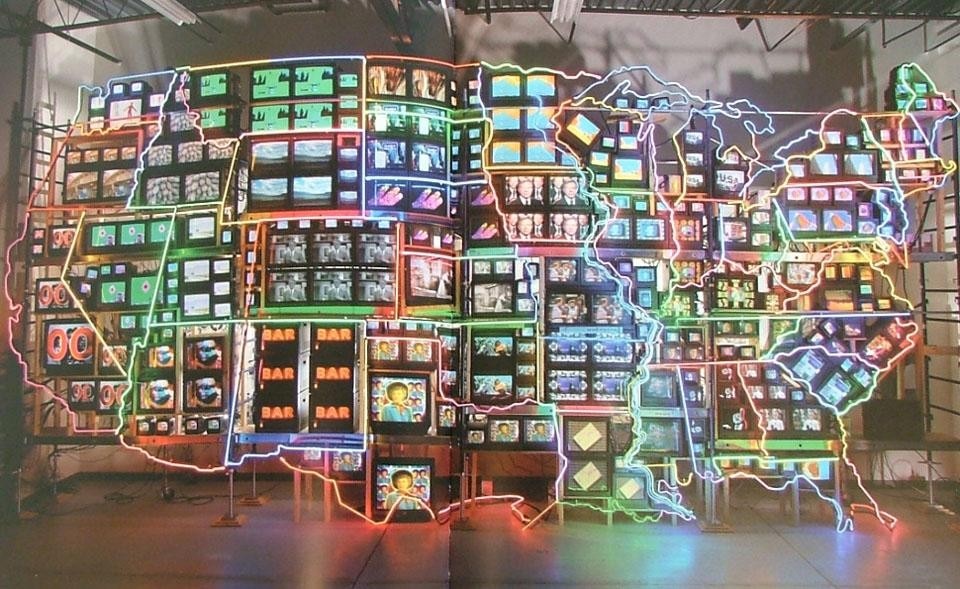

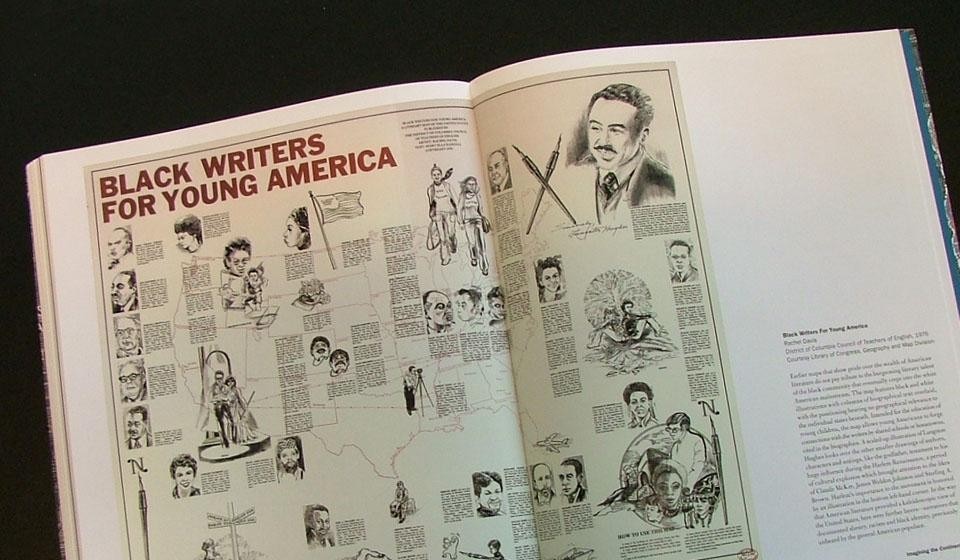

It appears that Google Maps Street View is creating Borges' paradox: mapping actual territory – more or less on a scale of 1:1. Between writing and describing, it seems that today's preference for video-photography, with its appeal to documentary "truth", is completing the unfinished. Of course, blind spots - areas not yet described - remain; just like the early days of cartography when the map of invention and of discovery filled the visual void by inventing a boundary, an island, "the other:" hic sunt leones. That the possibility of being able to see ourselves from above, of being able to say "we are here," is both knowledge and identity is clear from the patient work of cartographers who have always made the maps, as the places - reduced - of their own and others' conditions, available to the powers that be. But it is also apparent from the overflow of data mapping, from contemporary digital technology which requires specialized knowledge; geographic form often disappears and it becomes necessary to learn how to read the signs and measurements that do not necessarily correspond to traditional geographic coordinates.

In short, it seems that the authors have decided that the map is point of view and this in two senses: that of one's own position in relation to the object and that, transferred, of opinion.