Francesca Esposito: Les Rencontres is an event eagerly awaited by the world of photography. More than 20 years after the first exhibition, what does being the focus of this retrospective mean to you?

Chema Madoz: The retrospective in Arles is one of those exhibitions that, long-term, is a high point of your career, like the retrospective on my work held by the Museo Reina Sofia in 2000. It all takes on a different perspective at Rencontres, thanks partly to its huge resonance, and gives visitors a comprehensive vision of different ways of looking at things.

FE: You first trained in Madrid – how did you progress from that to the works exhibited here?

CM: I initially studied History of Art at the Complutense University in Madrid, where I started attending beginner photography courses. There were no professional courses back then and the possibility of using photography as a language was hardly considered. What immediately drew my attention was the opportunity to convey ideas and order the world as I see it via photography.

FE: How does a picture change from real to surreal in your mind?

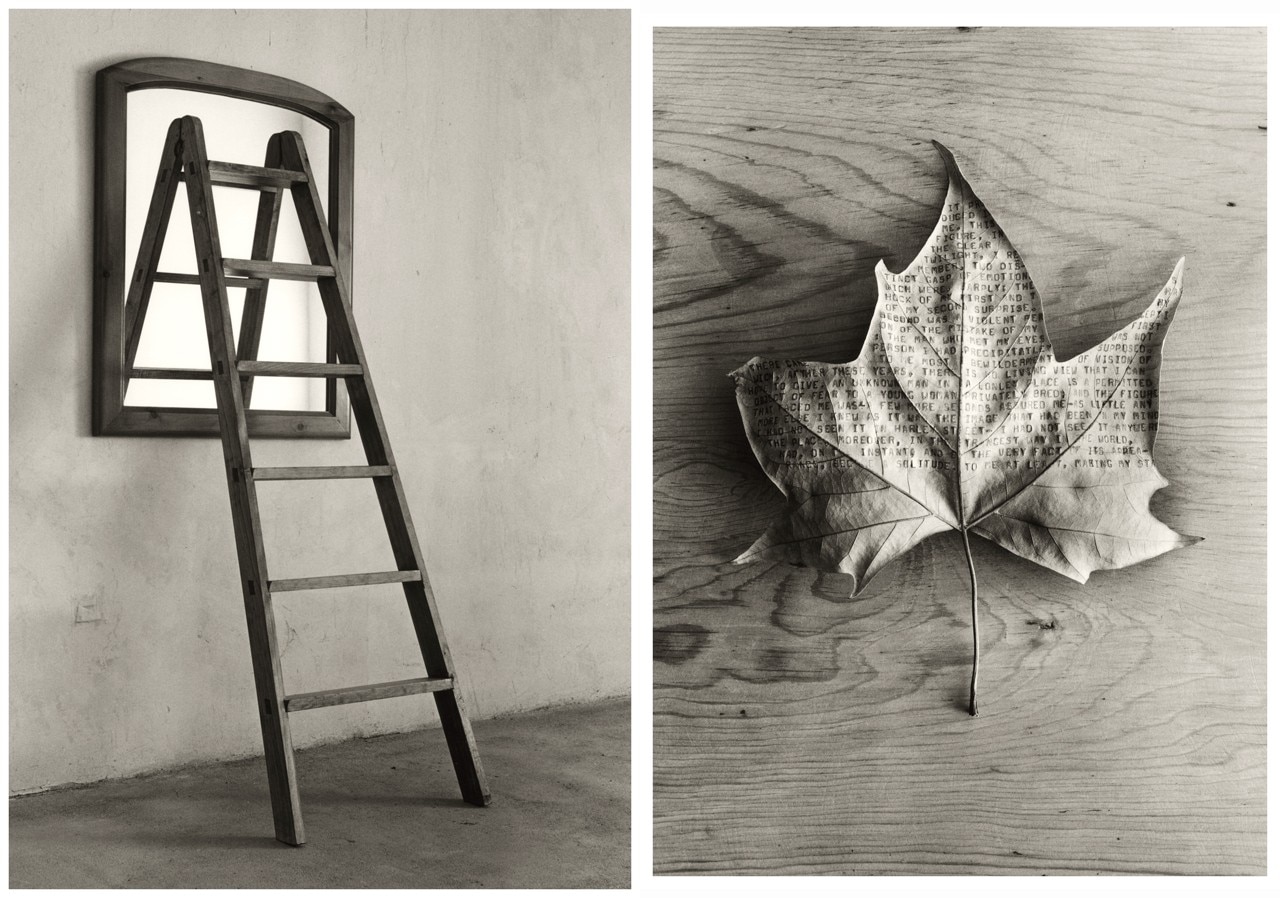

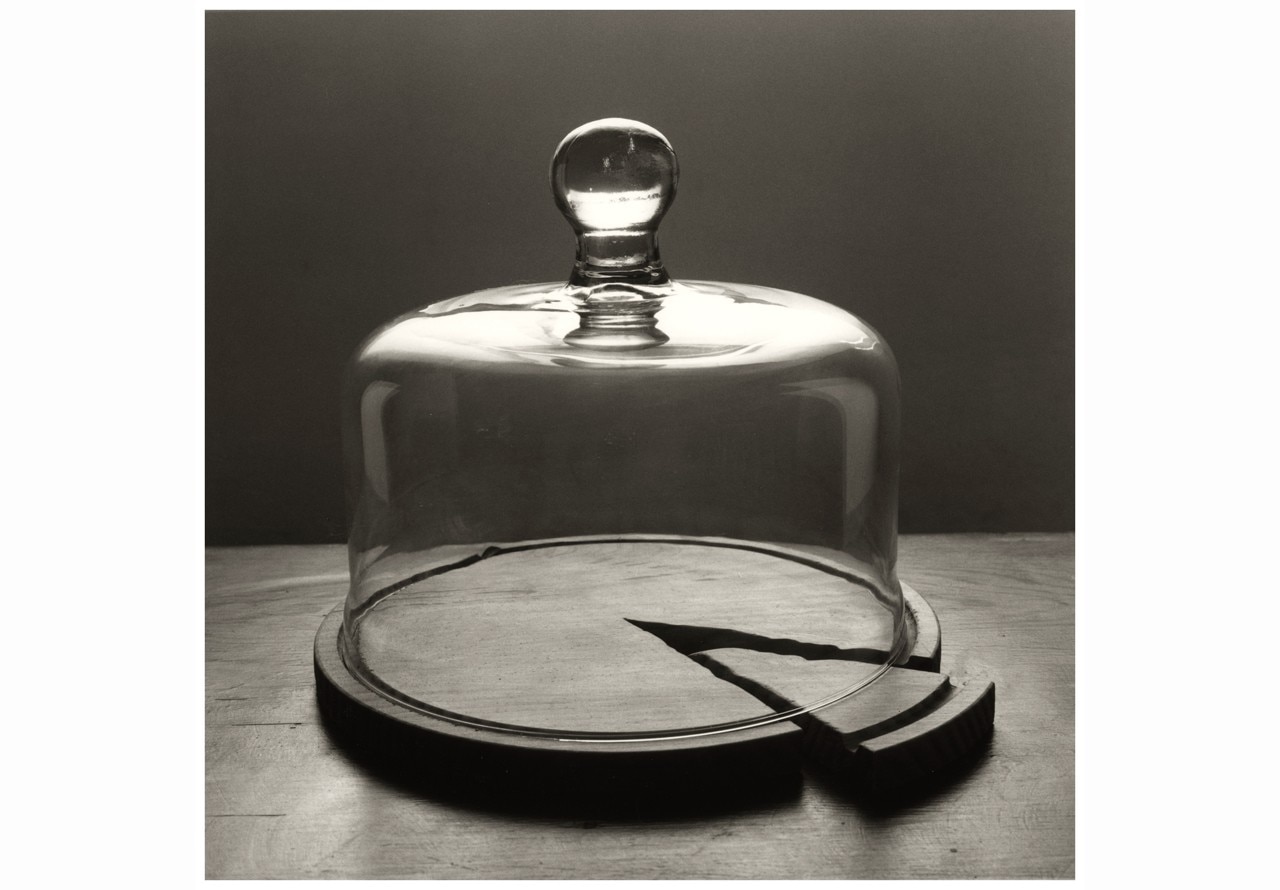

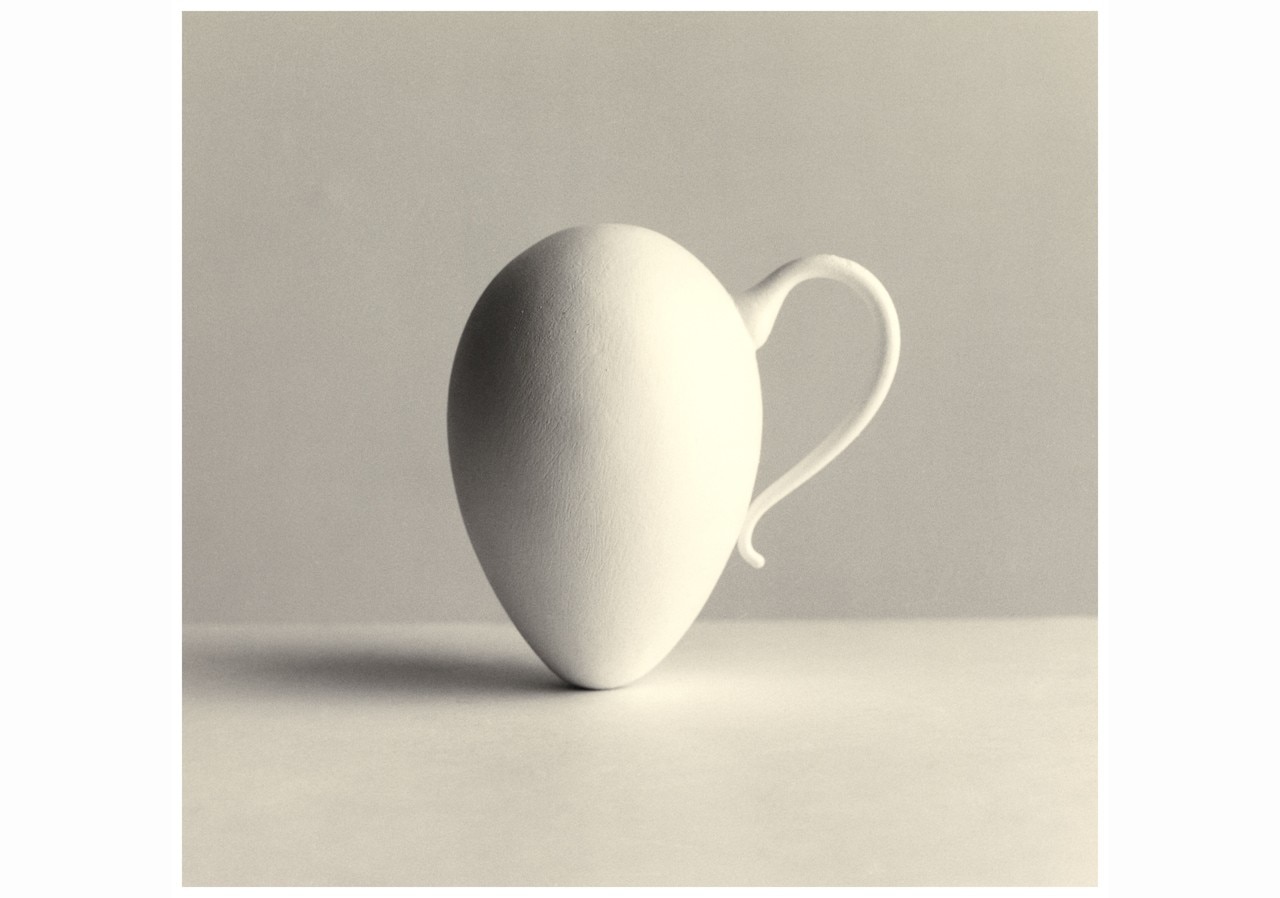

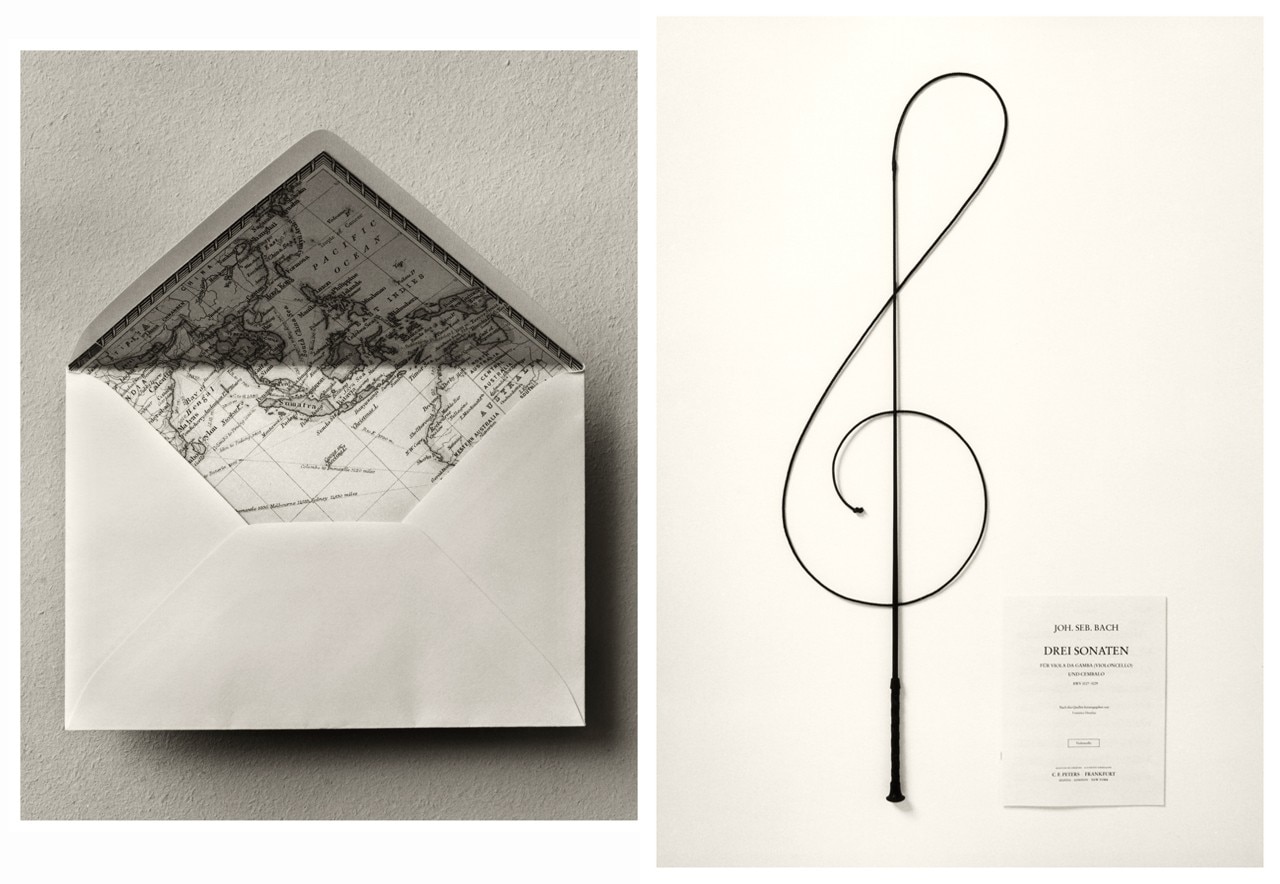

CM: My pictures are the product of contemplation. There is no firm moment, they can crop up at any time or anywhere. I usually do a small preview drawing, simply jotting down an idea and as a first visual approximation of the picture. Then, I look for what’s needed and work with it until I have elaborated the idea. The photograph is the final step and simply records what has been constructed. In this way, the eighth art plays the role associated with it - to preserve the memory of something that will disappear after being photographed.

FE: Is there a figure that best represents your mind?

CM: A self-portrait I created starting from an X-ray of my head; in it, the area of the brain is occupied by a cloud. It’s exactly the same shape as the brain and I see this cloud as symbolising the imagination and potential to adopt a myriad of different forms, like the games you play as a child.

FE: Let’s discuss technique: it all began with a Hasselblad. How important is your equipment?

CM: It’s not exactly like that. I started with a 35 mm camera and only later began working with these Hasselblads, which have accompanied me for about 25 years. It’s the type of camera that totally meets my expectations when I press the button. What interests me most is the concept and developing the ideas.

FE: How important is psychology in your work?

CM: It’s important in the sense that psychology focuses on everything that isn’t obvious but conditions most of our actions. I see it as a form that provides the background to things.

FE: Thinking back to the great Surrealists – Breton, Dalì, Magritte –, everything seems to have started with Freud. What do you think?

CM: Freud appears as one of my main references in some books on my work, especially when I prepare the pictures. It isn’t conscious on my part although I suppose Freud himself would have much to say about my lack of consciousness.

FE: It’s almost as if there’s a Spanish Surrealist theme running through your work, starting from Dalì.

CM: It isn’t hard to link Spain to the Surrealist tradition, especially when you think of artists such as Dalì, Buñuel, Mauja Mallo and some of Lorca’s books. Certainly, we could find a link with certain aspects of my culture but I fear it would not explain the current situation, which, in some cases, is closer to senselessness.

FE: Some of the photographs are filled with humour but also poetry. Do you see yourself as a poet or a photographer?

CM: I am a photographer who adopts a language that is a mix of a whole host of influences. I have always been interested in the brevity of my poetry and its ability to convey images with intensity and a few elements. I realise there is a link in this sense: a poet explores a word’s resonance and meaning to the same degree as I explore an object.

FE: What are you trying to communicate with your works?

CM: We could say that my work is a statement against dogmas and great truths. It’s a call for doubt, an attempt to look at everything around us from a new angle and without taking anything for granted or as already known. It is seeing the mundane as wild and unfamiliar territory.

FE: What should people feel when they look at your photographic metaphors?

CM: They ought to gain awareness. I would be happy if they left an exhibition of mine feeling dizzy at the potential offered by everything in their home.

FE: Who has influenced you more than anyone else?

CM: It’s a long list. I am interested in many artists who are frequently totally contradictory, such as André Kertesz, Duane Michael, Man Ray, Magritte, Cildo Meireles, Sugimoto and Joan Brossa.

FE: Are you working on a new project?

CM: I am always working. I’m currently preparing an exhibition of recent material that will be presented in my Madrid gallery, Elvira Gonzalez. Then comes a presentation in Madrid, an extensive review of my last six years’ work. At the same time, I’m preparing more exhibitions, with Michael Hoppen in London, one in Vienna and “Paris Photo” in November.

FE: We have often mentioned Surrealism in this interview. What exactly is it?

CM: Surrealism opens doors whereas explanations and their dimensions somehow close them. I don’t believe it’s necessary, although certainly some aspects of my work can be bound to this movement; but others might relate to Minimalist or Conceptual works. My work is absorbed through the eyes and, personally, I prefer not to give too many explanations. Let everyone draw their own conclusions.

–

© all rights reserved

until September 21, 2014

Chema Madoz

curated by Borja Casani

Les Rencontres de la photographie

Magasin Électrique, Parc des Ateliers

Arles