For more than 50 years now, the city of Genoa has been engulfed by floods about once every two or three years and pictures of its water-filled streets and piles of cars dragged into road junctions are beamed all over Europe.

You may think we have become inured to images of flooded cities. Why should we be surprised after seeing Hurricane Sandy ripping through Manhattan? Yet, there is something extraordinary about what happens in Genoa. Not because its flooding is any more dramatic than elsewhere but because Italy’s major port, seen via the portrayal of environmental disaster, offers a unique vision of this urban space.

Let us run through records of the most recent catastrophes, those of October 2014 and November 2011. Visual sequences such as this one reveal very few signs of the horizontal transfiguration that normally follows flooding the world over. Genoa’s fabric does not turn into a liquid expanse dotted with anthropic islets. It is in the vertical hierarchies that we see the disarray.

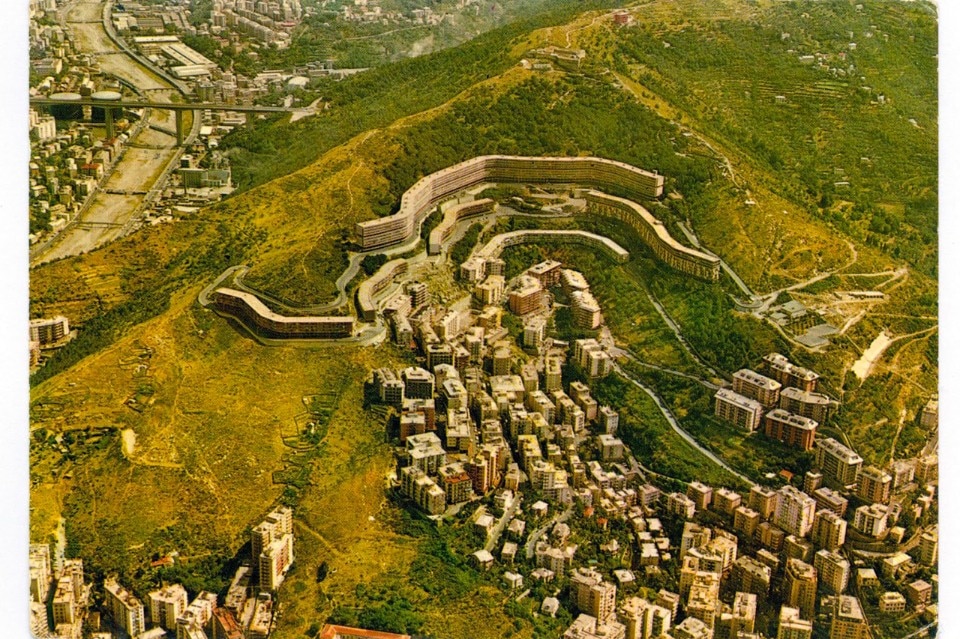

If we focus on those photographs, we come across cars perched on steps, narrow streets with no sky, chasms in which whole vehicles drown beside a dry pavement, slopes congested with buildings, buried rivers erupting through the tarmac, cascades of water and rural houses resting on viaducts as tall as skyscrapers. To the outside eye, there is no interruption between the elements overturned by the deluge and the local everyday urban framework. If the environment was inconsistent before the flood, what happens – paradoxically – is that this is simply underscored. The concrete backdrop surrounding the disaster restores a specific dimension both solemn and perverse to Genoa. Every time the city’s rivers overflow, this lays claim to the otherwise invisible existence of entire sections of the city.

Genoa’s fabric does not turn into a liquid expanse dotted with anthropic islets. It is in the vertical hierarchies that we see the disarray

“A Rome [real-estate] company tried to jam five apartment buildings into the side of the hill instead of four, one collapsed immediately and the hill split in two"

Daniele Belleri is a journalist who lives and works in Moscow. Among others, he has contributed to Afisha, Corriere della Sera, IL Magazine, Reuters, Volume and Wired Italia. He graduated from the Strelka Institute and has taught at NABA in Milan and at the Faculty of Journalism of Lomonosov Moscow State University. He is a co-founder of Granger Press. Twitter @dajamog