Null Object, the image on the cover of Domus 965 / January 2013, was conceived by London Fieldworks (artists Bruce Gilchrist and Jo Joelson); it draws on the artist Gustav Metzger's radical engagement with environmental destruction through art and political activism, informing a poetic application of technology.

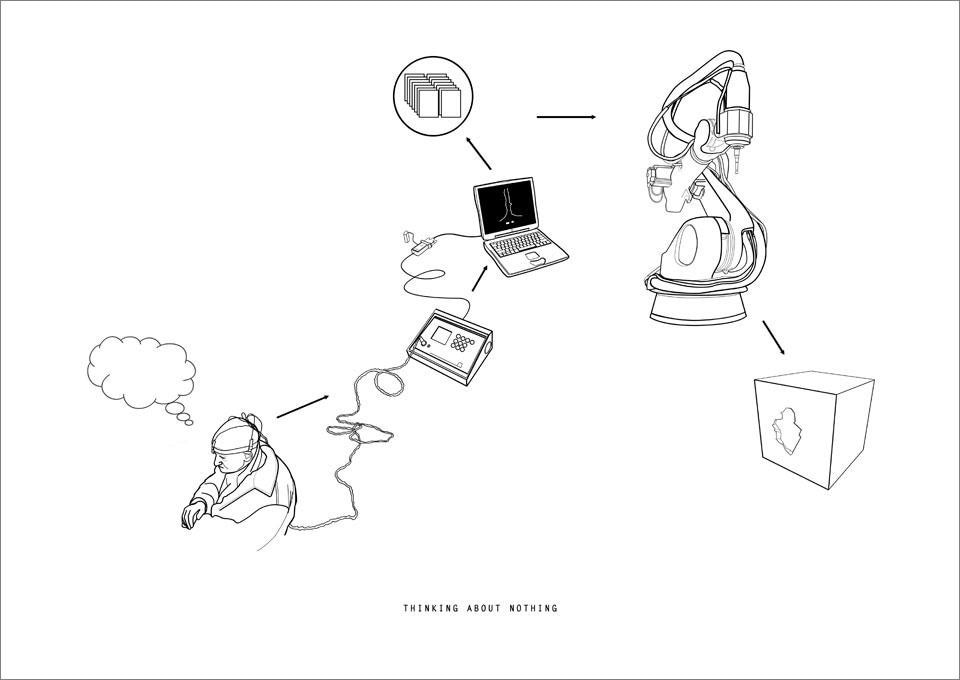

A brain-machine interface, computers and bespoke software are connected to an industrial manufacturing robot to produce a plastic form of art, functioning through complex layers of body, installation, biofeedback technology, physiological data, computer databases and software.

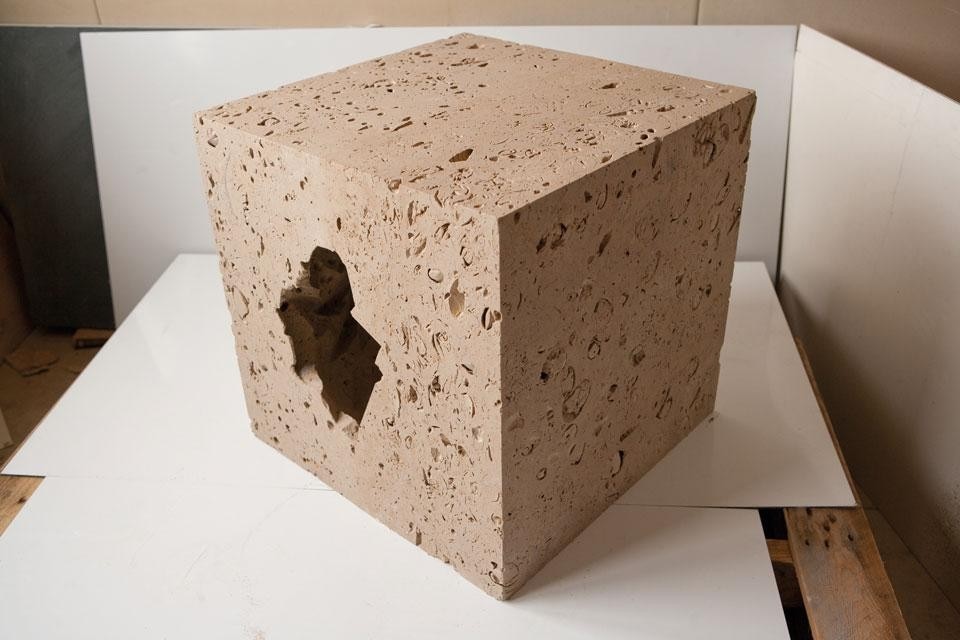

To create Null Object, a block of Portland Roach (a type of limestone deposited 145 million years ago in the Jurassic geological period) was cut into a perfect cube measuring 50 cm on each side and then excavated using a KUKA industrial robot. The form of the void created by the robot is derived from an EEG (electroencephalogram) recording of Metzger's brain while he attempted to think about nothing for a period of 20 minutes.

To give the wavelengths of Metzger's neural activity a physical form, the recording was compared to a database of similar readings generated from 1999 to 2012 by numerous subjects as part of a project titled Looking at Primitives. The image on the cover is a positive representation of this form.

The following interview with Gustav Metzger, Bruce Gilchrist and Jo Joelson was recorded in London in December 2012.

Jo Joelson: We were having a conversation with Nick Lambert, the chair of the Computer Arts Society, and Bronac Ferran of the Royal College of Art about "Event One", the first exhibition of CAS in 1969, an event Gustav was involved in at the RCA. They had the idea that they might revisit it, and through these conversations we began to learn about this first exhibition and Gustav's relationship with computers and technology. These conversations really inspired us to develop this new work and invite Gustav to participate.

Bruce Gilchrist: We see it as the latest iteration of a whole group of works that are database-driven. It goes back to the mid-1990s, when initiatives such as the Human Genome Project began to gain broad attention. At the time, there was a perception that databases were almost the subconscious of society — databases seem to run everything, and of course that is much more so today. They raise all sorts of issues about the state having control over citizens' data, how it is stored, and so on. We were also interested in the idea of distributed authorship, of creating an artwork by taking the artist out of the picture. We started from a database developed over 13 years that recorded perceptions of depth using autostereograms — images that at first sight appear unintelligible, but have three-dimensional primitive shapes embedded in them. The thinking around that was that these primitive shapes are like the building blocks of contemporary environments. We took this database of information regarding people's perceptions of depth and used it to interact with Gustav's EEG as he attempted to think about nothing.

JJ: For us there was an important connection with Gustav's past work on the concepts of emptiness, nihilism and extinction. In a way, creating a void was also a way of talking about society's obsession with the object. In this case we were actually removing materials to create an artwork, rather than building them up. The more materials artists and designers consume, the more we are in effect erasing ourselves. So the work is a combination of the material, the immaterial, and Gustav, his artistic career spent tackling the ideas of nihilism, destruction and the void.

These are themes you have been working on since the 1950s.

Gustav Metzger: People are terrified of the word destruction. This word is dangerous, mysterious, antisocial. But in relation to cosmology, what we are doing is just child's play, not serious destruction on a cosmological scale. On the other hand, we would not be here without the activity cosmology deals with. The attempt to bring some of those realities into art has been a fundamental, basic concern of mine since 1959, the time of the first Auto-Destructive Art manifesto. At the time, I said, "Look, do not imagine that this is safe — what is happening in our art world is all going to end in obliteration." It may be after an enormous time span in human terms, but in terms of the world, it is not such a huge time scale.

Rather than taking something physical and rendering it immaterial, as auto-destructive art did, we were taking something like an idea — or an idea of no idea — and inscribing it in something quite monumental, like a piece of Portland stone that has all these further resonances in terms of the architecture of authority—and geological timescales, of course

There's a bit of science fiction in Null Object, too. We were interested in Neil Stevenson's idea of "matter compilers" in his 1995 book The Diamond Age. These matter compilers are very utopian pieces of technology that one could find on the high street and would supply the basics for survival — food, clothing, blankets. You do not need money; the basics for survival are there for everyone. Five years later, around 2000, the New Scientist published an article about the first 3D printers starting to come into the mainstream. The leader on the front cover said, "Imagine an object and it will appear." So I thought, well, we can take this quite literally — if we connect neuroscience and these kind of machines, we could have a new process for the creation of objects, something along the lines of Stevenson's matter compilers.

,-London-Fieldworks,-2012.tif1.jpg.foto.rmedium.jpg)

BG: It is the embodiment of a juxtaposition. We've taken something that is evanescent, something that is super-ephemeral, and inscribed it in something that is monumental. A process that last for milliseconds in your mind is inscribed into material that is 145 million years old to create this space. It is interesting that when people look at Null Object, they think about caves, the very first houses, competing with animals for caves. At the same time you have this very high technology, this very rapid technological process of fabrication, so within this block of stone you have the two forces of high technology and geological time. This ties into the current interest in the dawn of art; there is a big show coming up at the British Museum next year about the first artefacts, which will include one of the first Venuses. When Gustav saw our first little model of the piece, he made a comparison with the Venus of Willendorf; it was probably something to do with the shape of the entrance to the block. Coincidentally, the Venus was carved from the same neolithic limestone that we used for the sculpture. Gustav, you made this parallel between geological time and prehistory, and I think that is quite explicit in our work. It is about juxtapositions — being awake, being asleep, reality, fantasy…

BG: Yes. We were very interested in a notion the neuroscientist Christopher Tyler introduced us to, a new research into what researchers call the "default mode" — in other words, the brain activities during the "idling phase" (for want of a better term). They are studying how the moment when the brain switches off is actually a very productive state. Artists and creative people know about this instinctively: if you are really struggling with a problem, rather than hammering away at it, rather than drinking loads of caffeine, you just forget about it—and somewhere in the subconscious, somewhere you cannot reach with your conscious mind, the thought is processing.

GM: I would like to bring up the name of Yves Klein. His work is central to what we have been doing—his project for a house built of fire. The heat keeps out and holds in what is necessary. The "immaterial", that was his term. It is now commonplace, but at that time was totally new. I am not comparing myself to Yves Klein — my text for the catalogue of Null Object deals with the same problem in a different way — but the parameters are essentially the same. How can we get hold of the immaterial, how can we push it around, how can it be pushed? This is what it is talking about, the immaterial, the fantasy. It is all a fantasy: just take one pull at reality, and the whole thing collapses. Add something to it, and it is another world.