Sometimes, as Brecht reminds us, it is more important to choose between being human and having good taste. Brecht, who spent some time (quite unhappily) in Hollywood, once described Los Angeles as a local version of Hell. It is very plausible to imagine that he wrote this because, while Los Angeles is inevitably contrived, it works so very hard at simulating good taste. Whether or not that makes LA more or less human is probably undecidable. Yet one imagines that Brecht might be pleased to find that Los Angeles (of all places) has recently sponsored the first significant exhibition and assessment of the works of Ettore Sottsass within a major American museum.

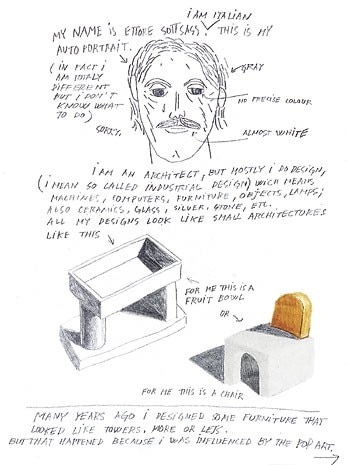

And, were he to visit the show, Brecht might also concur that Sottsass, perhaps more than any other present-day architect or designer, has time and again rejected not only good taste, or what Flaubert termed “…the level of stupidity attained by the bourgeois”, but he has also radically cast off any number of academic and disciplinary leanings in favour of a truly sovereign, self-determining and self-regulating cultural practice. If there is a Brechtian quality evident in Sottsass’s efforts it lies especially in the designer’s insightful recognition and acknowledgment of the affiliation between human relations and material culture (see Hans Höger, “Ettore Sottsass. Existential design” Domus 880 April 2005).

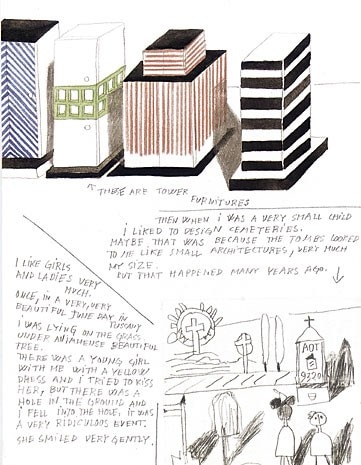

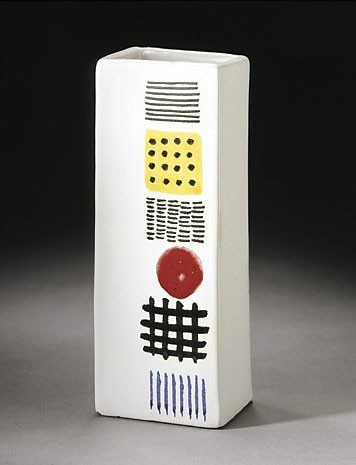

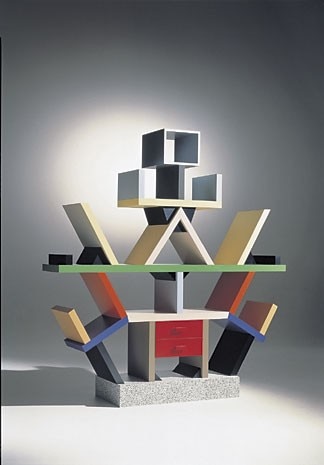

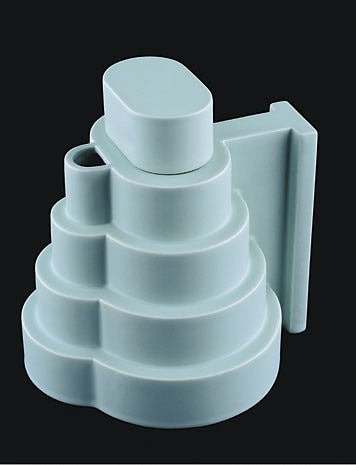

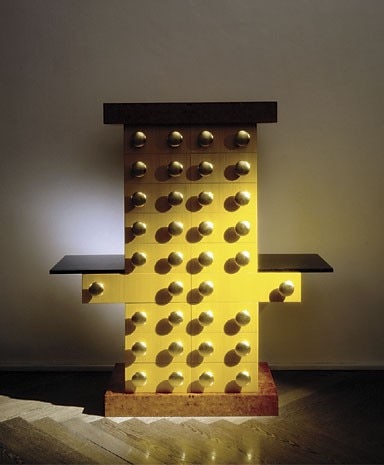

Therefore, it is worth noting that the most important disclosure delivered by this exhibition and the accompanying catalogue reveals the extent and depth of the human relationships that Sottsass has fostered across a career that has spanned some sixty-five years, bridged several disciplinary boundaries and produced numerous media and objects (architecture, furniture, glass, ceramics, jewellery and industrial design). Indeed, what stands out in this somewhat edited overview of Sottsass’s endeavours is his persistent and deeply collaborative and didactic spirit. While his work certainly retains and sustains his legacy, it is evident that Sottsass’s success, if such a term need be applied to his work, has depended almost entirely on the ongoing collaborations with artisans, galleries, craftsmen, labs, manufacturers, colleagues and clients that he has carefully seeded, nurtured and tended from his primary base in Milan. Each artefact or collection of objects is inevitably linked to a particular relationship that Sottsass has sustained and above all learned from.

In this follow-up to the more extensive exhibition staged last year at the MART Rovereto, the totality of the work displayed always seems wide-ranging and inclusive of variable processes as well as of remarkably shifting belief systems. If one can speculate that his relationships have been expansive and not reductive, flexible and not doctrinaire, then the didactic aspect of the work is in the end more masked because the artist finally offers no lessons, and provides no tutelage to the initiated or the uninitiated. Rather, like Brecht, who did not often depict the human (or human nature) within in the individual, but was instead motivated to characterise human relations above the illusion of an artfully manufactured interior life, Sottsass does succeed in making the familiar seem somehow strange. Sottsass permits the subject or user to be critically engaged enough with each designed object as to render it both unfamiliar and unique.

This “defamiliarisation effect”, what Brecht termed Verfremdungseffekt, requires one to critically consider the designed object rather than merely consume design production. Sottsass exhorts us to engage his artistic and ethical positions. In valuing human relationships over good taste, Sottsass and Brecht tell us that art must never entertain: above all it must teach. If anything, this long overdue US exhibition demonstrates that Ettore Sottsass, in the role of designer-architect-artist, has insistently chosen to be a humanist, to refuse the demands and realities of the market and reject any overtly puritanical dispositions towards utility, pragmatism and matter-of-factness. It is also clear from this exhibition that Sottsass’s entire oeuvre stands in patent resistance to the hegemonic cultural, economic and political imperatives of the 20th century and it wordlessly rejects capitalism for what might be termed as the pleasures and sanctity of cultural exchange. Accordingly, Sottsass’s unique point of view must finally be regarded as opposed to any number of the dominant isms that were mandated by the past century’s received orthodoxies – none the least of which is functionalism or what we Americans would more aphoristically call “design task orientation”, e.g. the value of work before pleasure.

Peter Zellner is an architect, writer and curator based in Los Angeles. He teaches at the Southern California Institute of Architecture.