The invention of mathematical perspective in the 15th century was the first skeleton key that helped painters to penetrate the mechanism of spatial illusion, but the trick soon was found to be too wooden and unsophisticated. In the short time lapse of a few decades, the most brilliant artists discovered that light could be a much more suitable expedient, and at the end of the 16th century, Caravaggio revealed its power to everyone. If art is illusion, then light imparted a perfect illusion. No depth can resist it, as the Dutch masters well understood, from Vermeer to Rembrandt, achieving the highest level of magic in interiors.

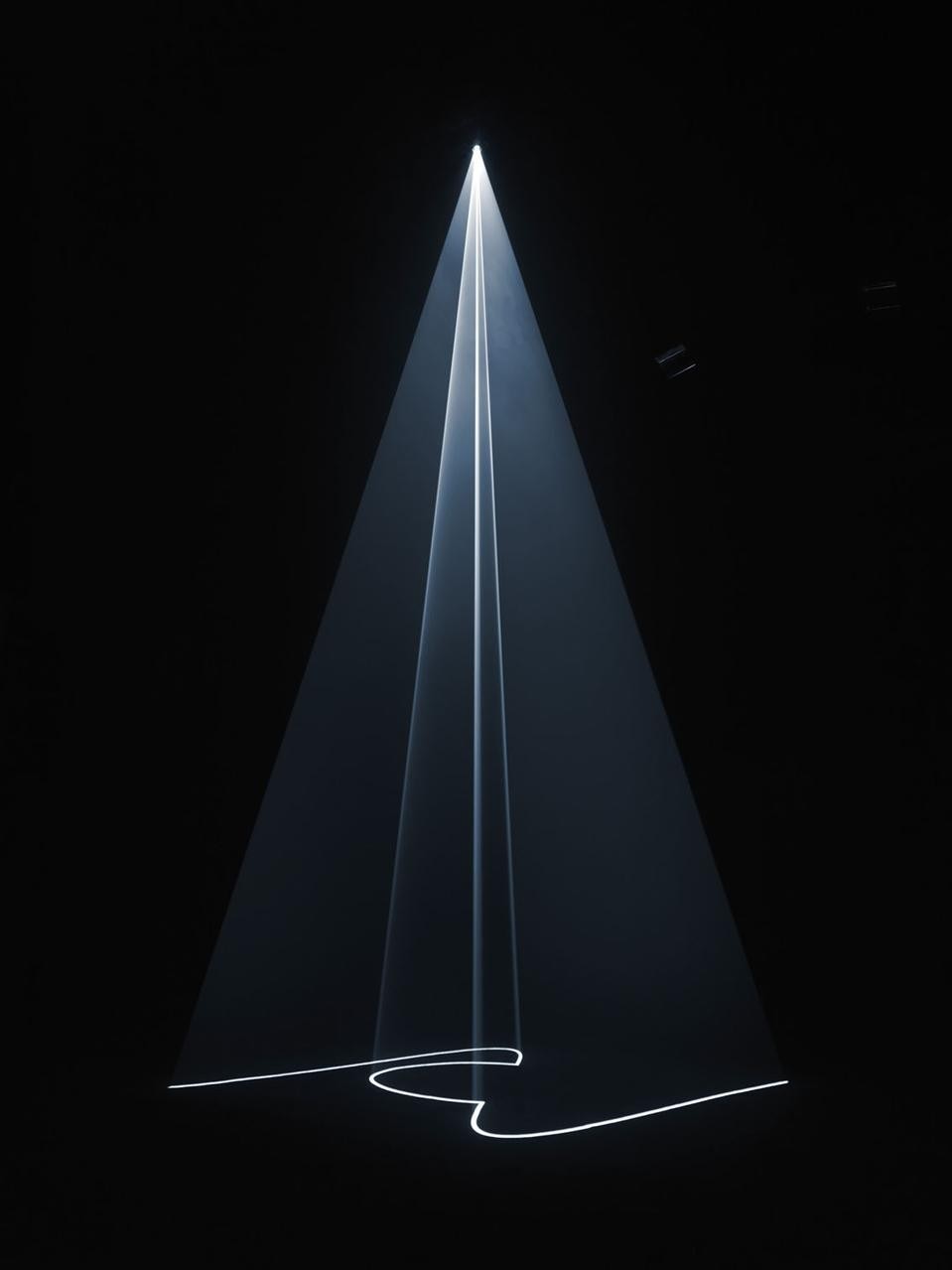

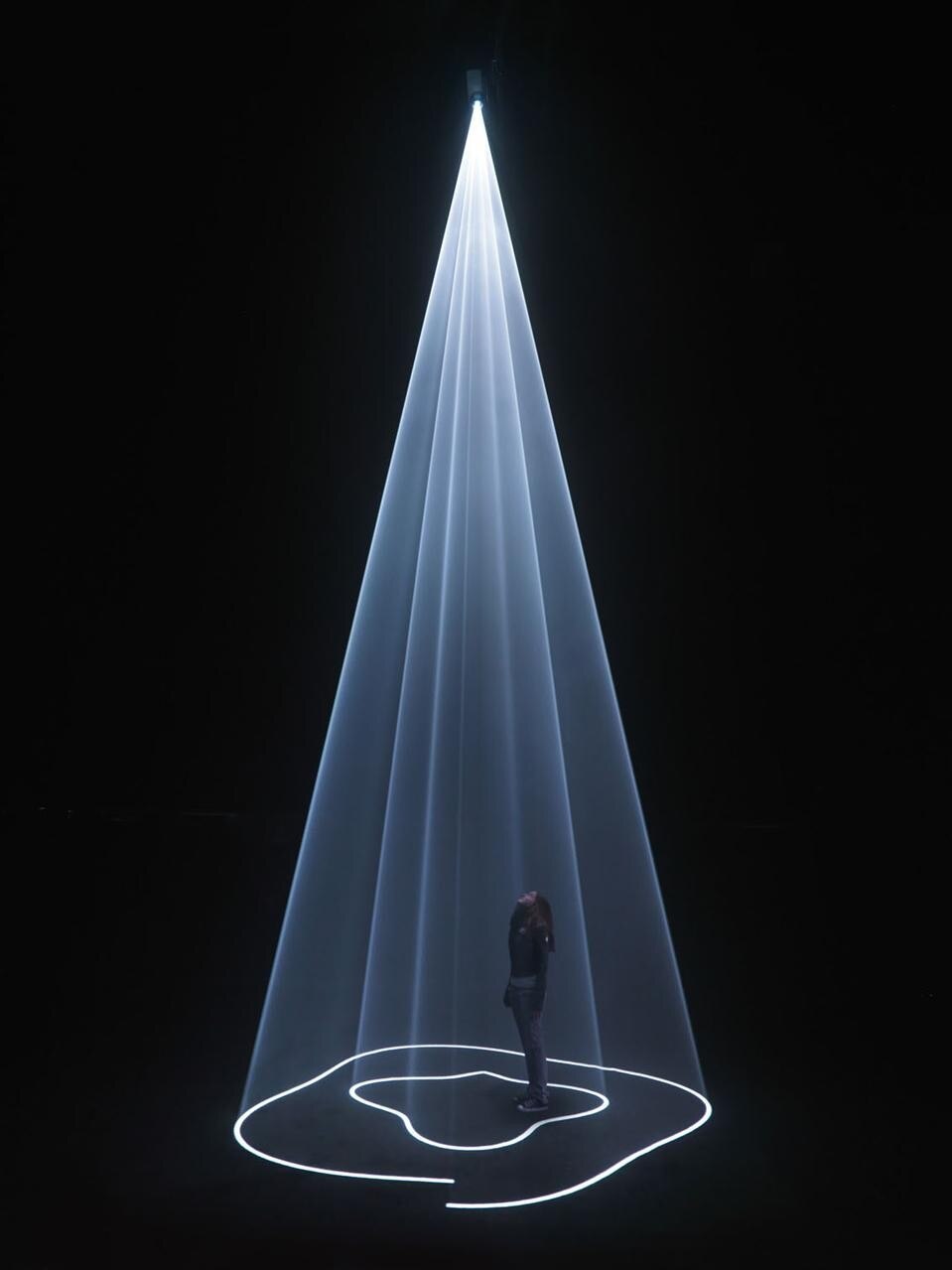

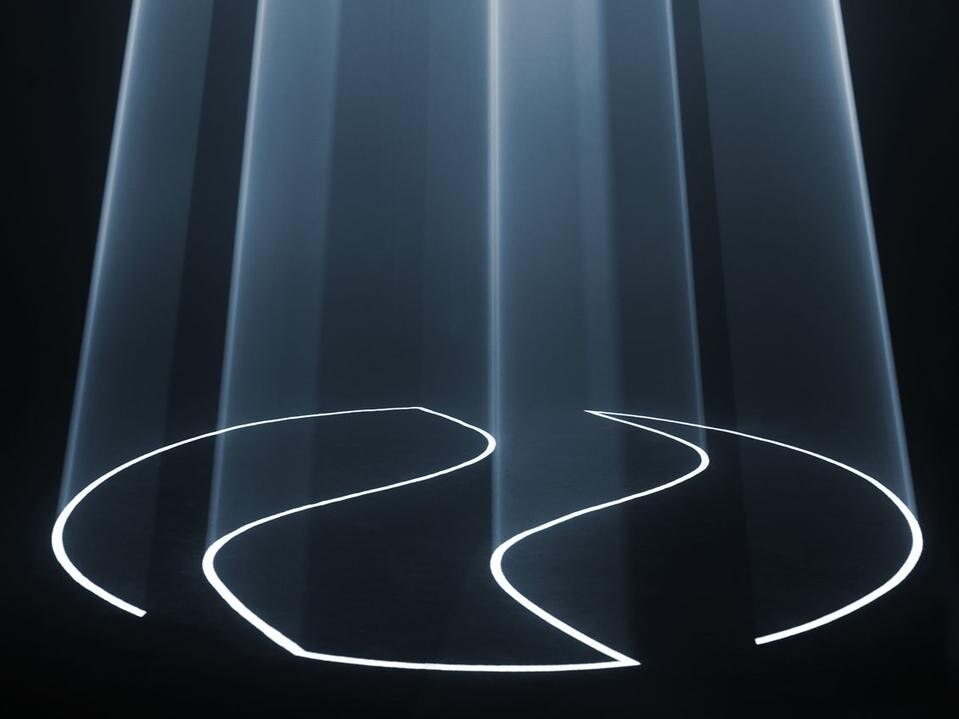

Although it is an ancient subject, the relationship between space and light is still much explored. One contemporary artist who has dedicated himself more than others to this theme is British-born Anthony McCall (1946), who has been a resident of New York City since 1973. Until June 21, Hangar Bicocca in Milan is hosting his largest show yet, under curator Serena Cattaneo. The huge size of the Hangar (which also features the permanent exhibit of German artist Anselm Kiefer’s magnificent towers) with its ninety-metre long and thirteen-metre high corridor – dimensions that are impossible to find in any other exhibition space - has allowed McCall to install seven projectors, each throwing a cone of light diffused from above. Hidden machines shoot out fog at floor level. Once the fog catches the light, it takes on the consistency of a three-dimensional diaphragm. Entering beneath the bundle of light, it feels like you need to push away a curtain or pass through a wall. The cone’s light expands and retracts, projecting white geometric lines on the ground, designed on a computer by McCall and in continuous movement. Hence the show’s title, “Breath”, for the way the space moves around the spectator’s body, enveloping it or retracting away from it.

“When I began in the ‘70s,” McCall recounts, “my interest was in the fundamentals of film. What you see in a movie has always happened at another moment and in another place compared to the real time of the projection, but I asked myself if it was possible to make cinema only in the present and in the same space that is shared by the spectators. That is why I worked precisely on the mechanisms of projection, independently from image. Then, with time, I realized that the cone of light from the projector gave life to a sculpture , a volume of space within which I could also represent the body.” It is curious to observe how the origin of these “solid light films” is a characteristic conceptual exercise in structurist and avant-garde cinema of the ‘70s, and how its effect can become an emotive one. Light that magically becomes similar to solid material cannot but trigger a reaction of astonishment: visitors experience physical and psychic sensations that are entirely new. Entering and exiting “walls” of light gives the feeling of stepping over a limit, a threshold between reality and dream, with a body that dematerializes and becomes capable of passing through dimensions that are normally inaccessible. In a word, you can feel like an extraterrestrial crossing through the barriers of light, walls and the confines of space.

With light, such things are typical, even with the most non-religious of artists, such as the American Dan Flavin, who was sent by his father to a Roman Catholic seminary when he was a child, only to develop an aversion to the Church that never let up. In his minimalist work, composed of anonymous, industrially produced fluorescent lamps, the spectator is faced with the perception of a spiritual aftertaste. “My fluorescent tubes never ‘burn out’ desiring a god,” Flavin answered when he was irked by people wanting to read a mystical meaning into his light installations. Yet as fate would have it, his last project was to design lights for a church in Milan’s degraded periphery (Chiesa Rossa, built in 1932 by Giovanni Muzio), transforming it into a spiritual space with the coloured light of his tube lamps. This is proof that every space is psychic and every light designs space. To separate them is impossible. Francesca Bonazzoli