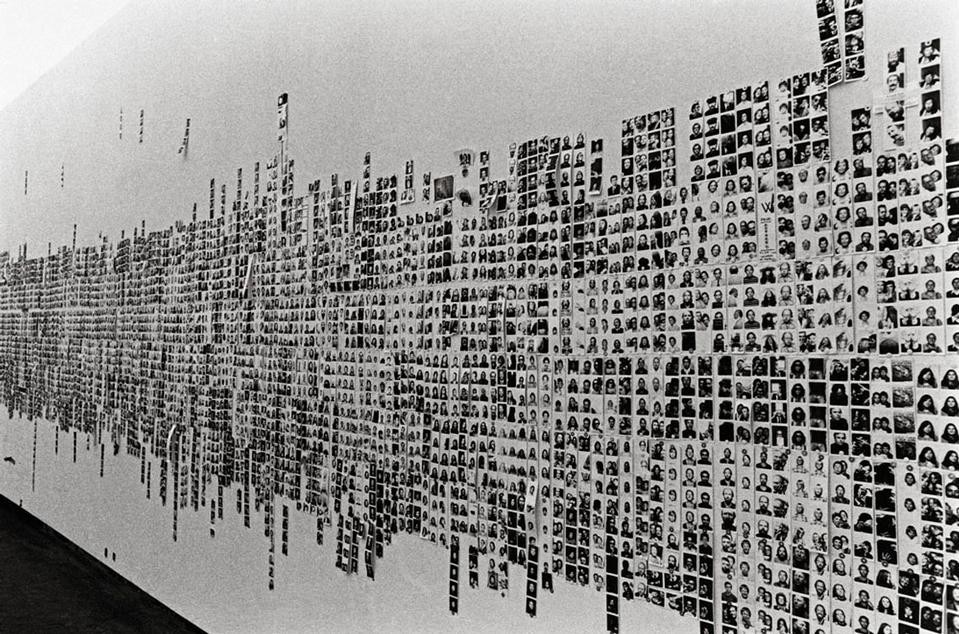

This year, more specifically, the Biennale seeks to investigate the relationships that tie people to images and vice versa, telling the stories of the anonymous lives we know only through the images that are left behind. This explains the title "Ten Thousand Lives" which is also an explicit reference to the 30-volume work by the same name, Maninbo, written by the Korean author Ko Un. The former Buddhist monk who participated in the Gwangju insurrection of May 18, 1980, for which he was imprisoned in solitary confinement for two years, systematically used the memory of all people - real or historical - that he had 'known' as an antidote to going mad. From 1982 to the present, he has, based on that experience, completed more than 3,800 portraits in words, a kind of personal encyclopedia of the human race.

In choosing the portrait, Gioni created his own encyclopedia in Gwangju. He amassed a collection of works and artists from over thirty countries from Afghanistan to Japan through the scouting work of 50 international curators. The final selection includes over one hundred artists with works produced between 1901 and 2010. Alongside this collection, there are, of course, many new commissions, which will enrich this unique vision of the world of Asian art. In order not to lose the important research that lasted over a year in unknown lands, Gioni decided to contain those excluded from the exhibit in the volume I Am Not There, a kind of 'starter' to be consumed cold - before the real Biennale - an operation in line with his work as curator of the Berlin Biennial in 2006 (with Cattelan and Subotnick) or of last year's show at New York's New Museum, "Younger Than Jesus."

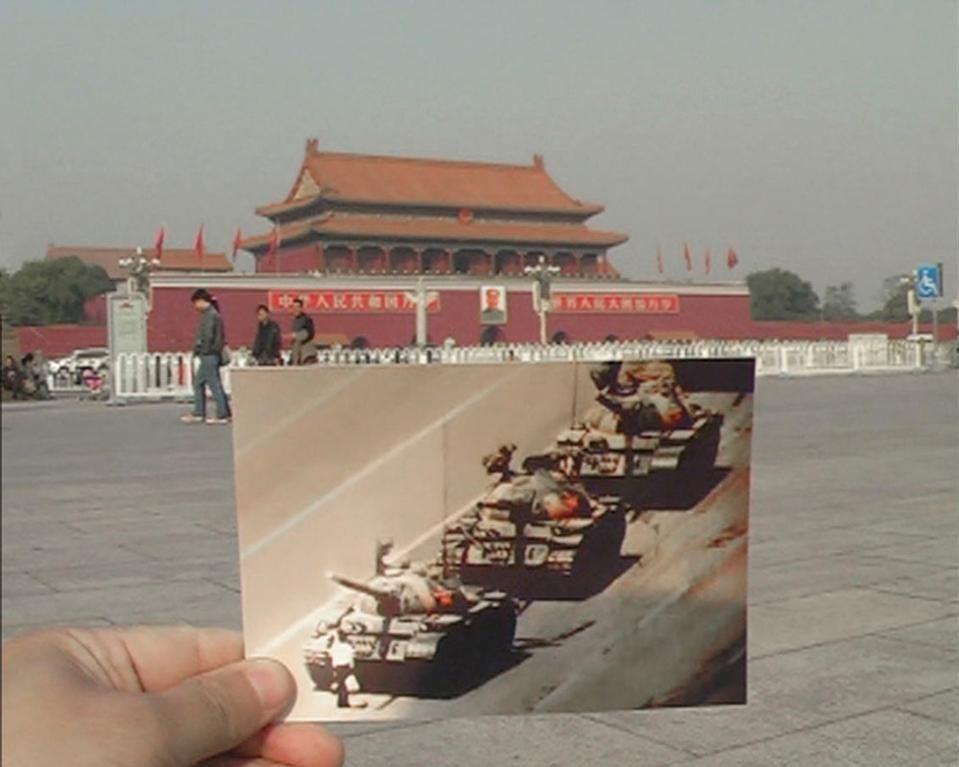

What Ko Un did with words, Gioni did with images, which are in fact the most common and 'democratic' tools with which we all represent our world - a world literally suffocated by the images themselves. It is the obsession with the image that animates and informs the whole Biennial this year, with its investigation of a topic that is as timely as ever, explains the curator.

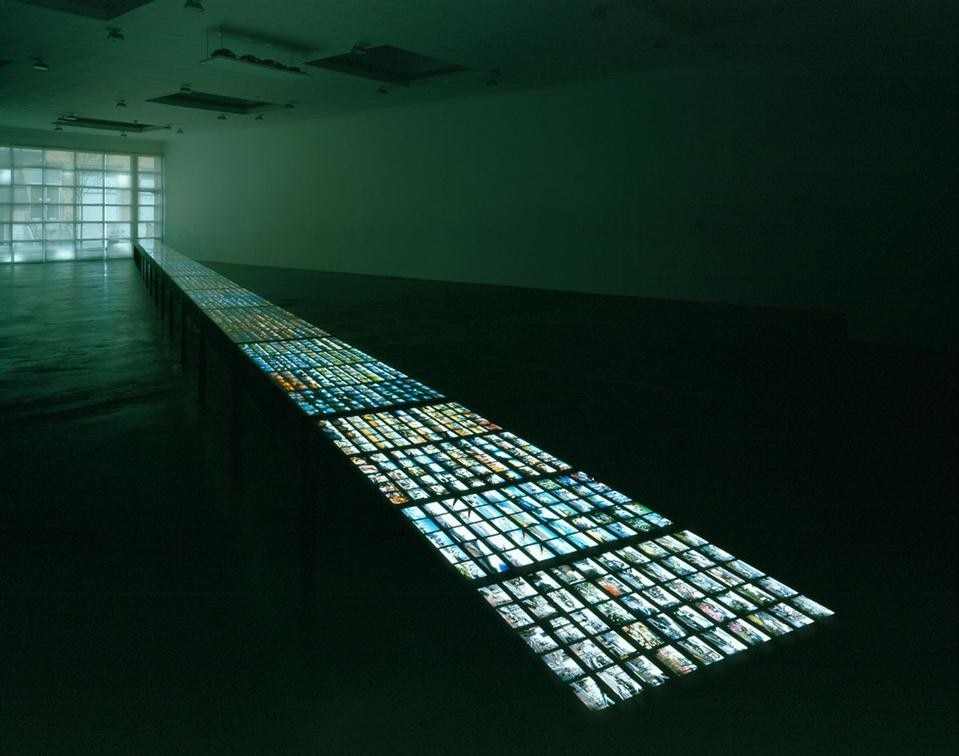

"We live in a hyper-figurative culture. Today the image industry is society's main activity: 500,000 images per second are uploaded every minute on Flickr, which grows on the average of 7 million images per day. On Facebook, there are more than three billion images; just Americans take an average of 550 photographs per second and the price for reproducing an image can run as high as 14 million dollars, a figure that is incredibly out of scale if we compare it to the price of $74 - 75 million for a painting by Mark Rothko. Today's prices for images according to industry standards and popularity far exceed those of art."

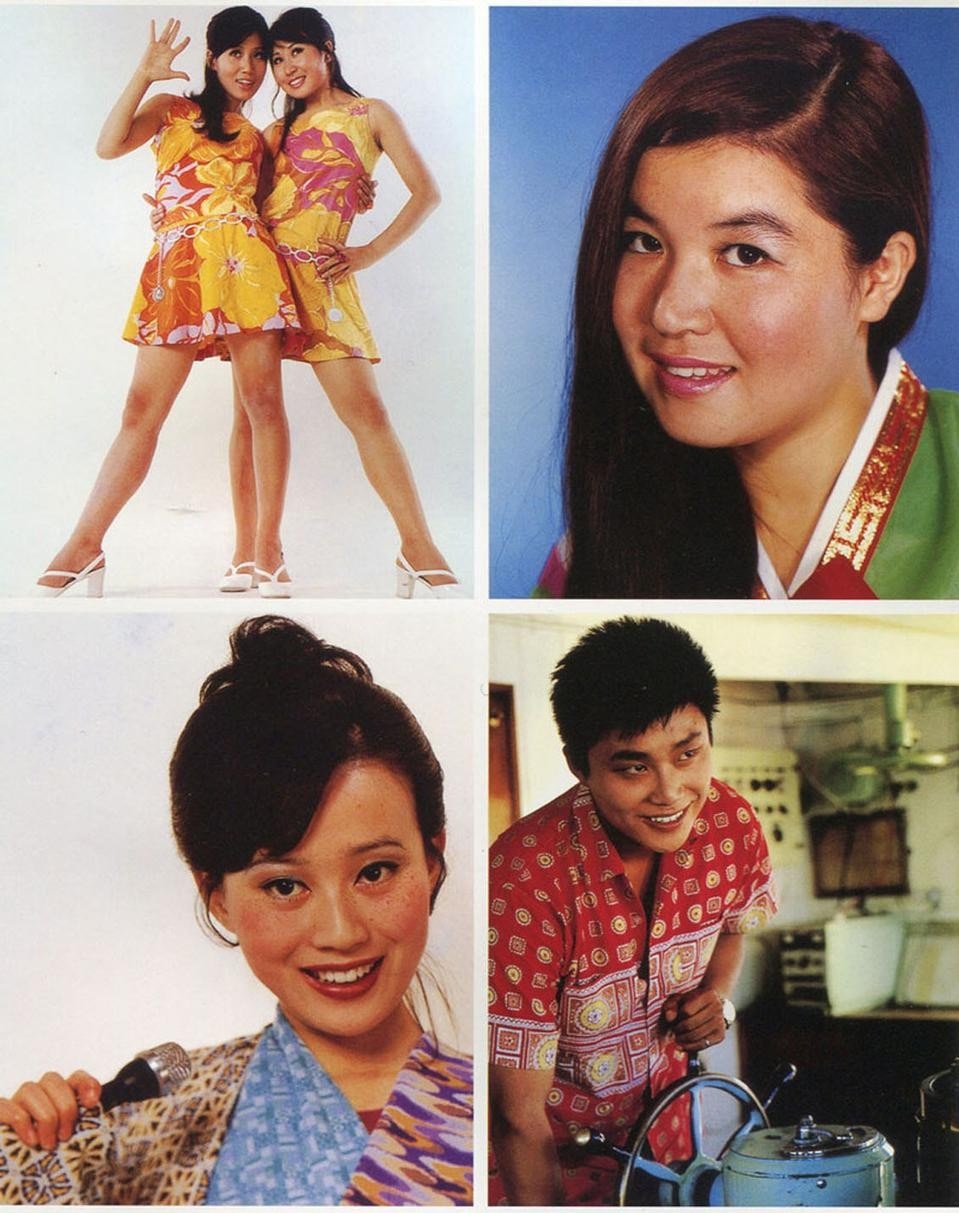

Gioni's vision expanded the common selection criteria to move beyond the boundaries of what is usually considered art to embrace artifacts that have achieved this status over time. This is the case of the album of photographs by Ye Jinglu (from 1901, the oldest work on display) who, every year, had a portrait done of himself so that not only does the life of a person unfold before our eyes but so does the history of China. Also in this category is the footage shot by Chinese farmers who used the videocamera for the first time as though it were a still camera, producing a family gallery. Or the disturbing images of the Tuol Sleng prison in Cambodia (where 17,000 people were exterminated): 99 portraits of prisoners snapped before their execution by a member of the Khmer Rouge army who, in this way, saved them from oblivion.

The power of images will be celebrated in many ways in Gwangju. Guo Fengyi has spent his life doing large drawings as though they were as talismans to cure diseases (including SARS); Thomas Hirshhorn collects images from the internet of the bodies of exploded suicide bombers while the Dutch collective Useful Photography presents 57 posters of Jihad martyrs thus confirming how we create martyrs and celebrate our heroes through images. Sometimes, love for images translates into its opposite. "Iconophilia" becomes iconoclasm: in the 1920s photos by EJ Bellocq, who erased the faces of prostitutes whom he portrayed; in those of Hyejeong Cho, analyzing iconography of the "mother" through Christian Japanese representations; or in the work of Huang Yong Ping, in which a Buddha is devoured by vultures.

There will also be hyper-realism as in the work of Paul Fusco, the photographer who accompanied Robert Kennedy's body on the train from NY to Washington telling the story of the participation of ordinary people in the nation's grief.

Gioni's most ambitious project still remains that of moving the entire collection of 103 statues of Rent Collection Courtyard out of China for the first time. These were created between 1965 and 1978 in Szechuan province and became the symbol of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Harald Szemann had already tried to do this but with no success. It would be a truly striking way to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of the Gwangju insurrection.Loredana Mascheroni