The magical encounter took place at the 2010 Venice Biennale when Koolhaas saw Rotor at work and decided to open the doors to OMA's subconscious. Rotor, experts in the demolition of false superstructures, worked for months like a hound: everything was annotated, classified and stored (the index of the archive is 17,000 pages long). Rotor lived in and observed the OMA environments. And this was the origin of a database that counts over 3.5 million images (not including models, documents, and scattered pieces of other things that go beyond the specific project) from the four OMA offices throughout the world, as declared in the video installation in which the unsuspecting viewer is warned that it is impossible to view the material in one day. It takes 48 hours of continuous viewing to scroll through the images at a rate of several frames per second.

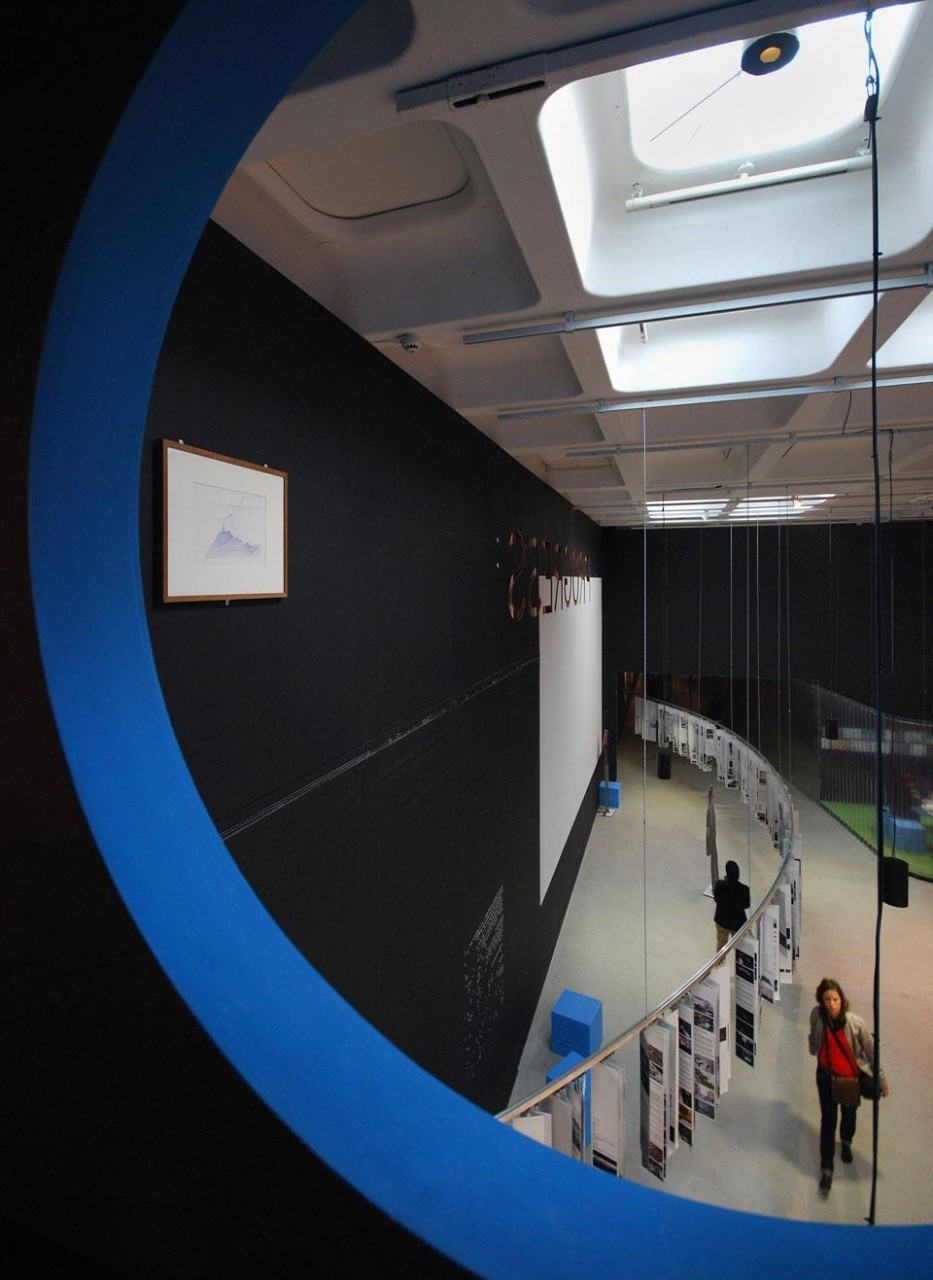

Everything is offered in an ambiguous form of disorder in which the visitor feels strangely at ease because it is disorder that accompanies the truth of the research process.

One shouldn't say anything beyond this. It's useless to try to convey the work of a collective like OMA—philosophical, political, economic, ecological thought expressed in buildings, films, masterplans, interior design, studies, research, ethics and design practice. It's useless to even attempt to store (and digest) everything on display. It's humanly impossible; there is too much information. What can be absorbed from the OMA/Progress show is the centrality of criticism and auto-criticism; the recognition of reality as a given upon which to base the imaginary. What is startling is how Rotor revolutionizes the idea of the architecture exhibition. An architect's works are expected to be presented as objects, put there to be understood; and viewers are ready to understand them as they always have—through drawings, plans, models and details.

Rotor states, "The real problem of architectural exhibits is that they can't show what they promise—meaning Architecture." Everything is offered in an ambiguous form of disorder in which the visitor feels strangely at ease because it is disorder that accompanies the truth of the research process. Nothing is hidden or concealed by coatings of representation. Everything is exhibited like pieces of work-in-progress in a large factory. Notably absent from the OMA/Progress exhibition: rhetoric.

Emilia De Vivo

OMA/Progress

Until 19 February 2012

Barbican Centre

Silk Street

London