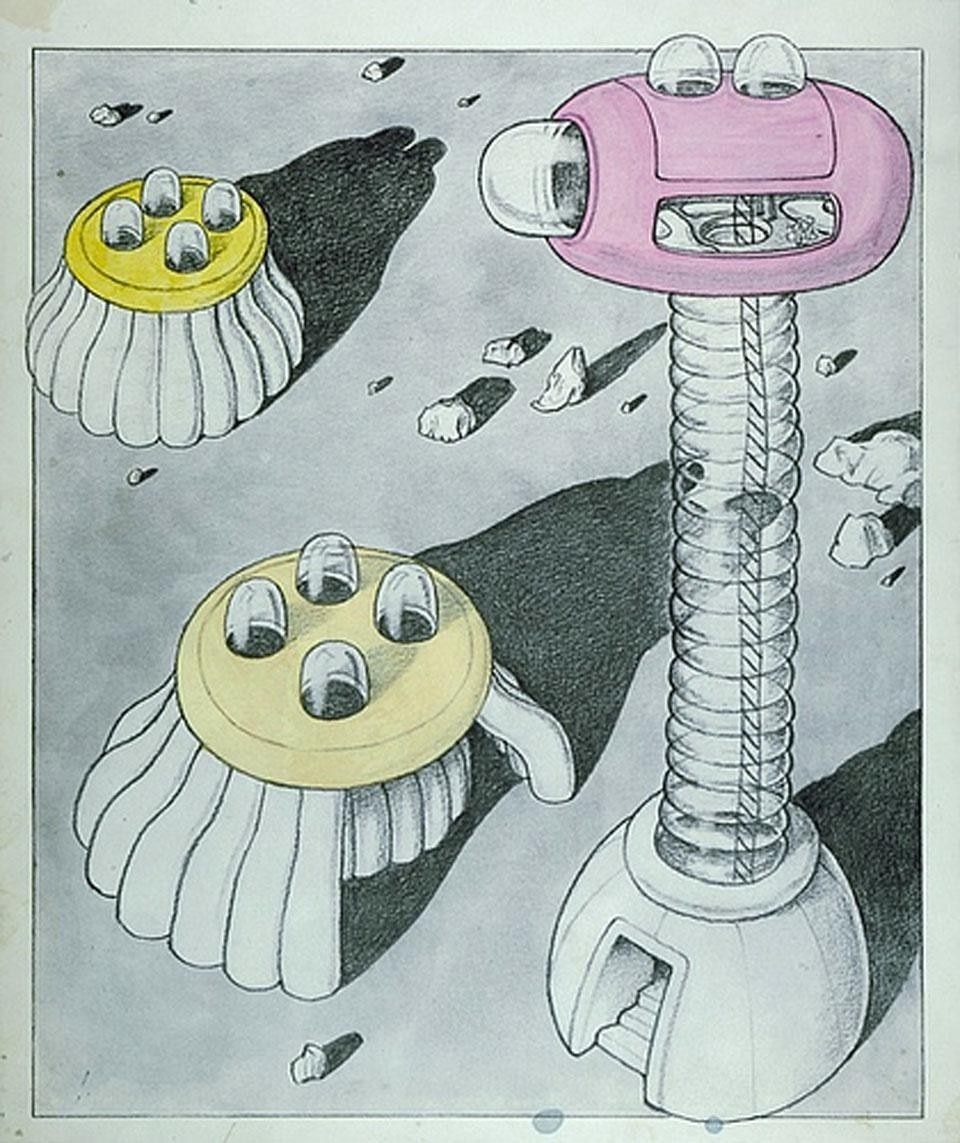

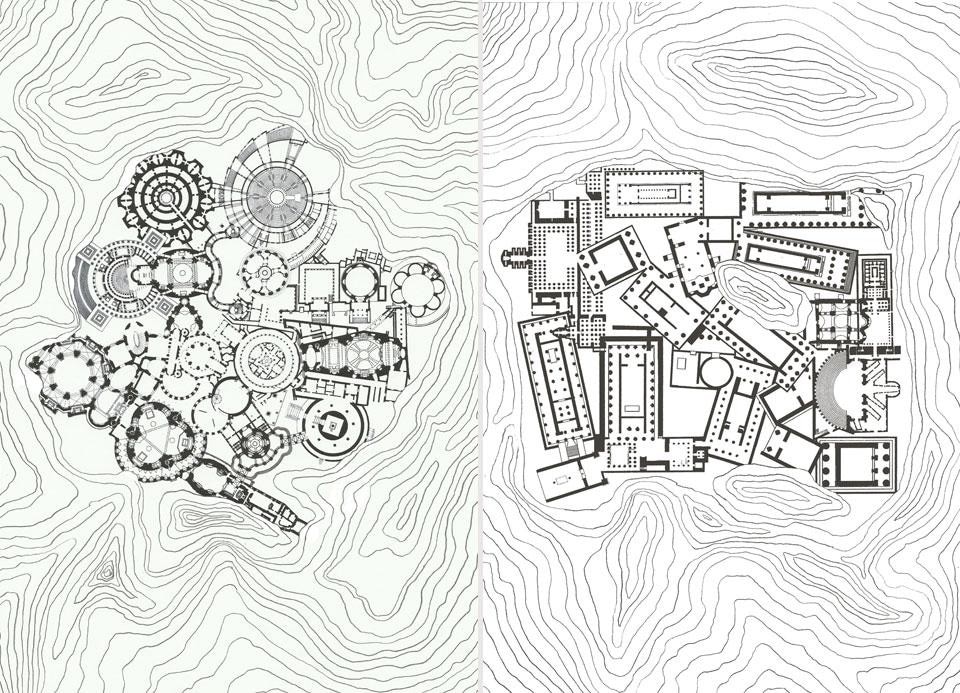

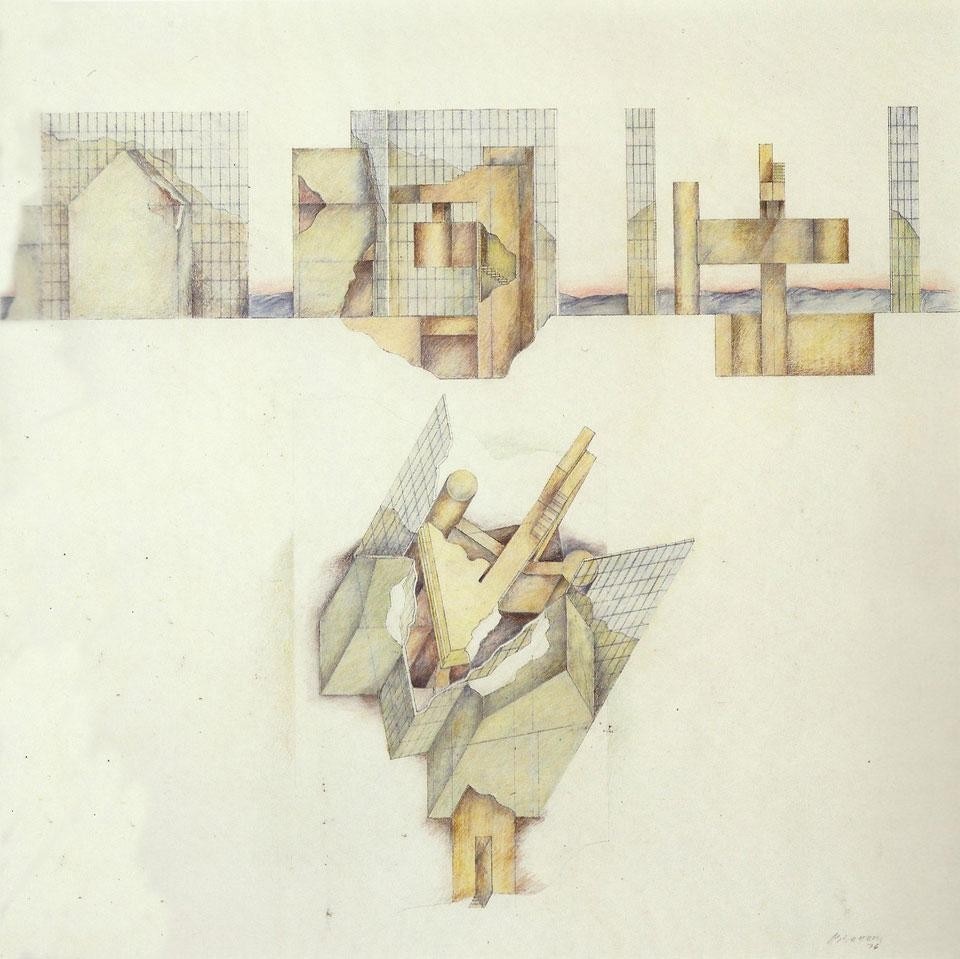

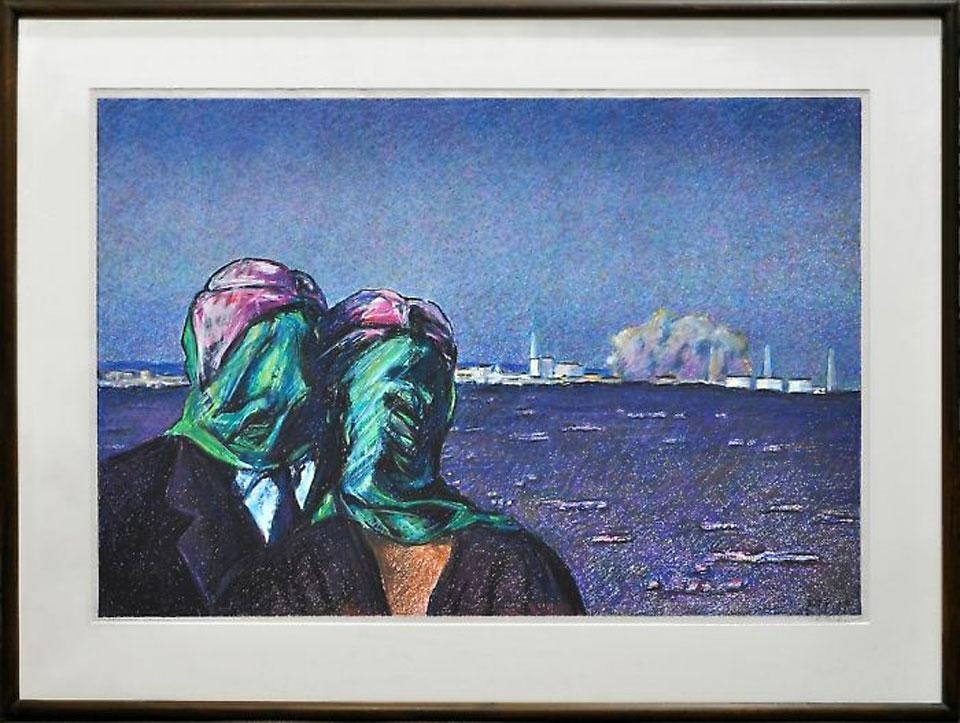

The map is the protagonist in the latest exhibition curated by Gianni Pettena for the Galleria Giovanni Bonelli and marks the launch of the gallery's Milan outpost. The map is at the centre of the tale that unfolds through six important voices, connected thanks to a geographic instrument. Raimund Abraham, Hans Hollein, Max Peinter, Walter Pichler, Ettore Sottsass and Pettena himself run into one another on an imaginary plane between Bolzano and Vienna, in that Mitteleuropa they all originate from. Each of these six protagonists was born within a fifty-kilometre radius of each other, as if an imaginary compass had marked, ab originem, the intellectual friendships that form this gallery of human and professional portraits. The map traces unexpected trajectories of kinship and brotherhood (Peinter and Sottsass were first cousins); describes in detail shared attitudes and passions; explores under the microscope reports and stories that, due to the sporadic knowledge of the sources, we risk losing track of.

![Top and above: <em>Vienna e dintorni</em> ["Vienna and surroundings"], installation at the Galleria Giovanni Bonelli, Milan. Photos by Floriana Giacinti Top and above: <em>Vienna e dintorni</em> ["Vienna and surroundings"], installation at the Galleria Giovanni Bonelli, Milan. Photos by Floriana Giacinti](/content/dam/domusweb/en/architecture/2013/01/11/vienna-and-surroundings/big_403594_2442_Vienna-e-Dintorni-10-copy1.jpg.foto.rmedium.jpg)

The convention of representation in plan seems to be the primary language with which Gianni Pettena presents himself to the public: two maps that take something of a backseat prove to be the necessary tool for understanding a poignant display that draws on the 1970s to describe, obviously, a piece of the future

![<em>Vienna e dintorni</em> ["Vienna and surroundings"], installation at the Galleria Giovanni Bonelli, Milan. Photo by Floriana Giacinti <em>Vienna e dintorni</em> ["Vienna and surroundings"], installation at the Galleria Giovanni Bonelli, Milan. Photo by Floriana Giacinti](/content/dam/domusweb/en/architecture/2013/01/11/vienna-and-surroundings/big_403594_4677_010-Raimund-Abraham----Seven-gates-to-eden--1976-installazione-galleria-Bonelli---foto-Floriana-Giacinti1.jpg.foto.rmedium.jpg)

Vienna e dintorni: Abraham, Hollein, Peintner, Pettena, Pichler, Sottsass ["Vienna and surroundings"]

Galleria Giovanni Bonelli

Via Porro Lambertenghi 6, Milan