Letter on Domus 882

by Jan Kaplicky

I have read Domus since 1956, almost 50 years. I always thought that your magazine was about architecture, design, beauty and people. In the last few months it has become just a political journal. I was shocked, horrified, angry and sad when Domus 882 June 2005 arrived. 22 pages and 3 covers full of North Korean propaganda. Propaganda of a regime with a horrific human rights record. A country led by a dictator responsible for the deaths of more than 2 million of his people. Hunger used as the main weapon. Nuclear weapons. Supporting terrorism abroad. Concentration camps. Prisons. What more do you want me to say? Your pictures and text support that evil empire without a single critical comment. Phrases like “visionary plan of the leader” are laughable.

How are we supposed to take you seriously? Not a single word about starving people, prisons and camps. People brainwashed to be ‘yes robots’. Scared people. Your favourite hotel costs $750 million of state money to build. How many lives could that save? This is all the product of the magazine and its editor. His team sitting comfortably in one of those famous Milano coffee places trying to pretend they are fashionable left wing intellectuals. How pitiful. Who you are trying to impress? Yourselves. Certainly not architects. Certainly not. There is no philosophy on these pages. Maybe admiration of that regime. Please note that even Jean Paul Sartre refused to accept Stalin’s horrors. I am reminded of the picture of Jane Fonda sitting on a North Vietnam anti-aircraft gun. How naïve that was. You must stop these meaningless intellectual exercises. You cannot support cruel regimes. Mussolini built railway stations, Hitler autobahns and Stalin underground systems, often using slave labour. Kim Jong-Il Hotel. Millions of people affected. Millions of people dead. What you talk about is not even architecture. Possibly only piles of bricks or concrete.

The Ryugyong Hotel is certainly not architecture. It is empty. Without people. It cannot be designed and used by brainwashed robots. Modern architecture cannot exist without free human beings. Not a single word about that in your article. Please do wake up. You are isolated. You are alone. It is too dangerous. Please look around for beautiful things, they are happening. Your responsibility is enormous to young architects, students and humankind.

This cannot and should not be of any inspiration to anybody. Please think new, beautiful, useful and particularly progressive. Think of the human cost of these projects whilst having another coffee in Bar Magenta. What is the next issue of Domus going to be about - Mussolini, Hitler or Mao? Mugabe destroying buildings? Next time celebrate creativity, not destruction. Please!

Jan Kaplicky

Jan Kaplicky (Prague, 1937) founded the London-based practice Future Systems in partnership with David Nixon in 1979. Recent projects include the Media Centre at Lord’s Cricket Ground in London and the Selfridges store in Birmingham.

Media, Architecture and Geopolitics

Insights

by Stefano Boeri

Since our very first issue, we’ve made it clear: we believe that today’s architecture is an instrument, both useful and necessary, for looking at the world. We think that the act of observing, describing, interpreting space and the built environment is one of architecture’s resources and helps us understand the community we inhabit.

We believe that the landscape - the territories continually defined by our movements, re-invented by our desires, punctuated by what we build - is an excellent metaphor for our society. Why? Because the local is a treasure-chest rich in details and clues that can tell us about the forces that permeate our daily lives. Forces that at times are manifest only in the space that surrounds us, perhaps just for a few instants, like footsteps in the snow.

Architecture’s political dimension is not to be found in the labels we attach to our projects, nor in our magniloquent political declarations; rather it lies in the production of useful and critical knowledge about the world that surrounds us. Knowledge that is useful because it is critical. With this in mind, in the past months, we have visited the ex-USSR’s nuclear “ghost cities,” followed illegal immigrants across the Mediterranean, documented the history of an infernal prison in Buenos Aires, and charted the savage exploitation of migrant workers in Shanghai’s massive building sites.

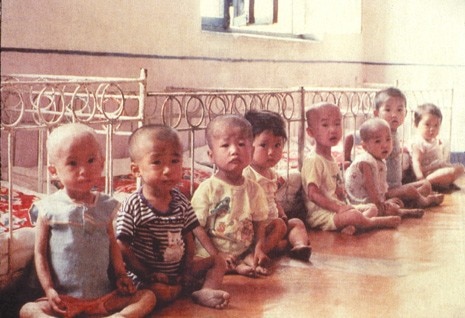

It was with the same interest in investigating local space that we travelled to Pyongyang. We described, without feeling the need for ideological proclamations, a horrific city delineated by oversized, shopless roads in which citizens take on the appearance of extras on a movie set. Citizens who inhabit decrepit high-rises and move on foot because public transportion is virtually nonexistent. Armin Linke’s photographs depict a city invented and realized all at once by a dictator and his staff of architects. A city punctuated by immense, semi-abandoned monuments that revolve around Ryugyong Hotel, a gigantic ruin, symbol and consequence of the failure of a regime that is perhaps trying to escape from its suicidal isolation.

But there is something else. Pyongyang’s sinister landscapes are not to be quickly dismissed as the tangible proof of the existence of a “kingdom of evil.” As we pointed out, one can perceive something familiar in them. Something eerily familiar to the eye accustomed to the imagery of western science fiction. It’s as though in the aftermath of the bombing in 1952 of Pyongyang (an entire city razed to the ground seven years after Hiroshima and Dresden — have we all forgotten?) someone like George Orwell or Ridley Scott decided to create, without a hint of irony, Western culture’s worst dystopia. It is impossible to remain indifferent to the bizzarre collection of architectural caricatures built by the North Korean nomenklatura. They created a city populated by automata unable to exercise their free will, the incarnation of an absolute regime isolated from the world, nevertheless capable of unscrupulous recourse to the symbolic language of Western democracies. Whether we like it or not, we are a part of that nightmare.

For this reason, we launched a call for architectural and geopolitical ideas to rethink Pyongyang’s immense concrete pyramid (www.domusweb.it/domus/ryugyong).We used this ruin as a symbolic bridge, a tool to denounce this dictatorship while at the same time opening a crack in the regime’s isolation, without resorting to the use of “smart bombs”. The quality and sophistication of the proposals we are receiving from around the world (even from inside North Korea) confirms our intuition: at times architecture is capable of insights that the politics of spies and international diplomacy cannot perceive. We truly regret having disrupted Jan Kaplicky’s black and white vision of the world, but it was worth it.

Stefano Boeri