This article was originally published in Domus 621 / October 1981

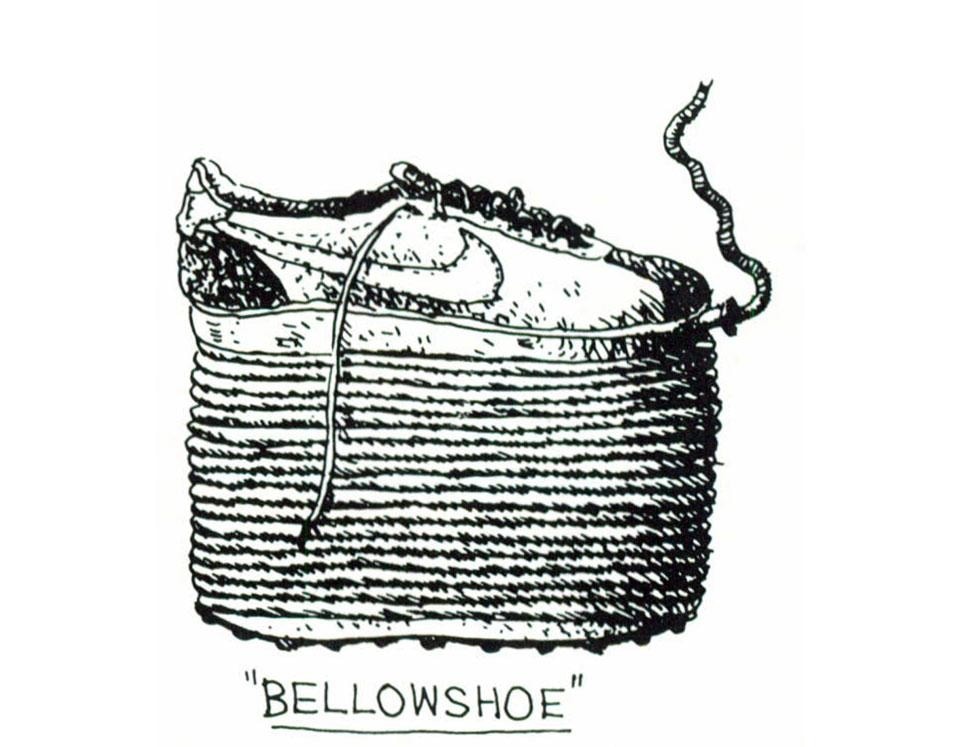

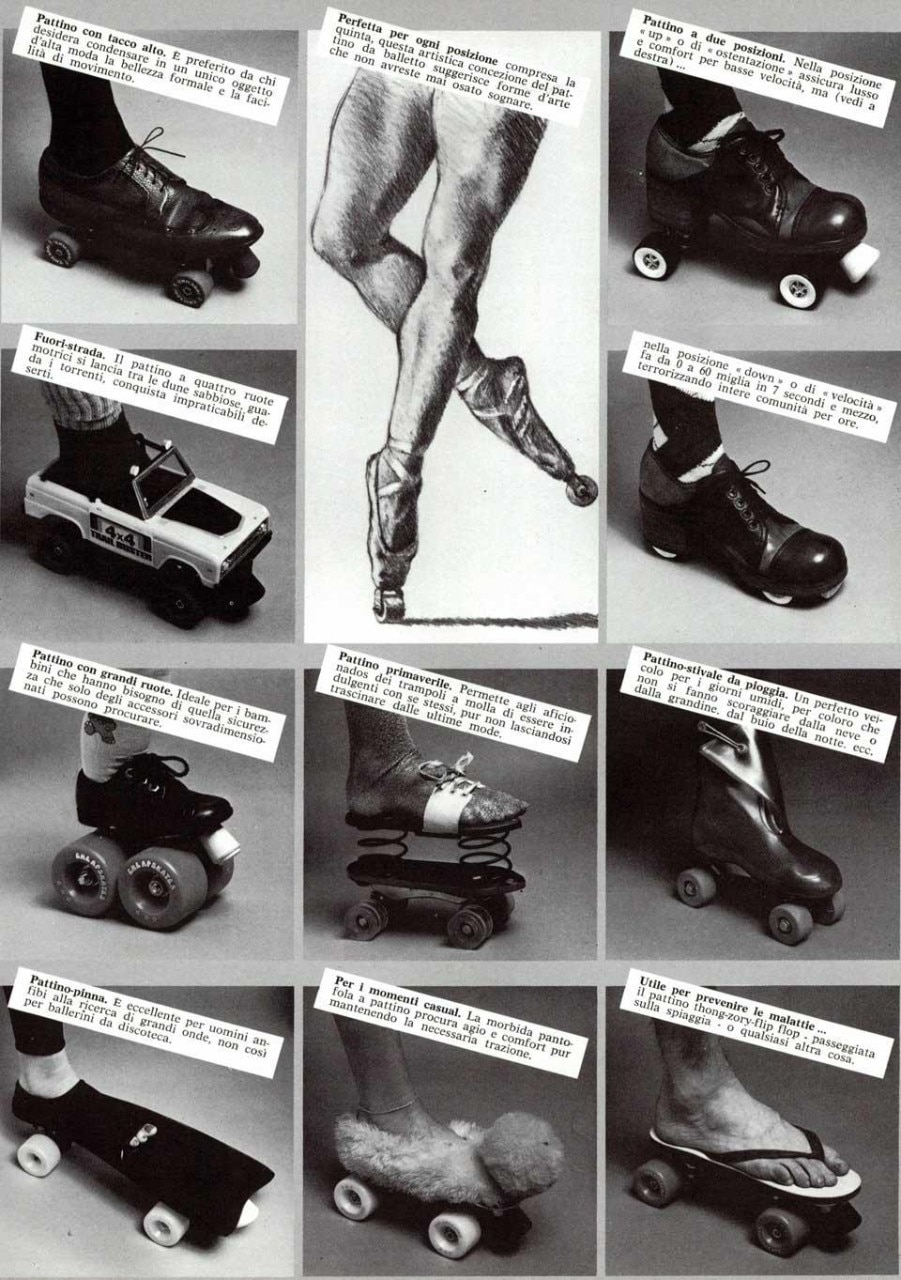

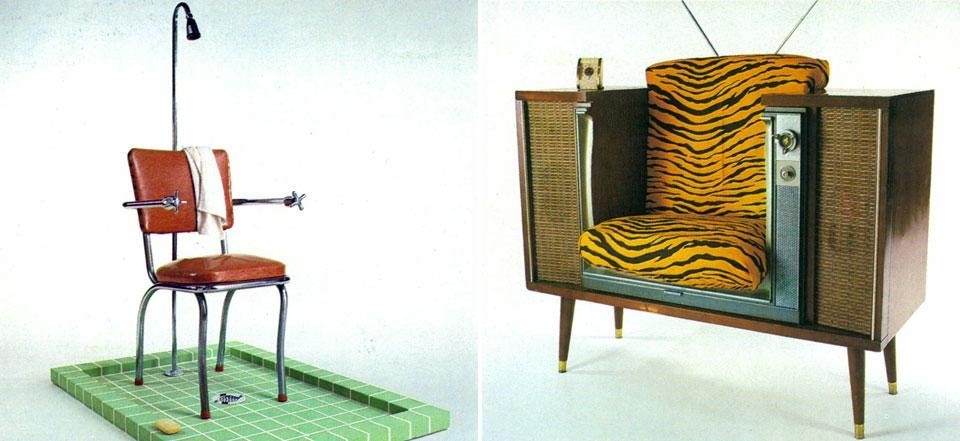

Ideas, design and creations by Phil Garner: an expression of the limits and neuroses of American society

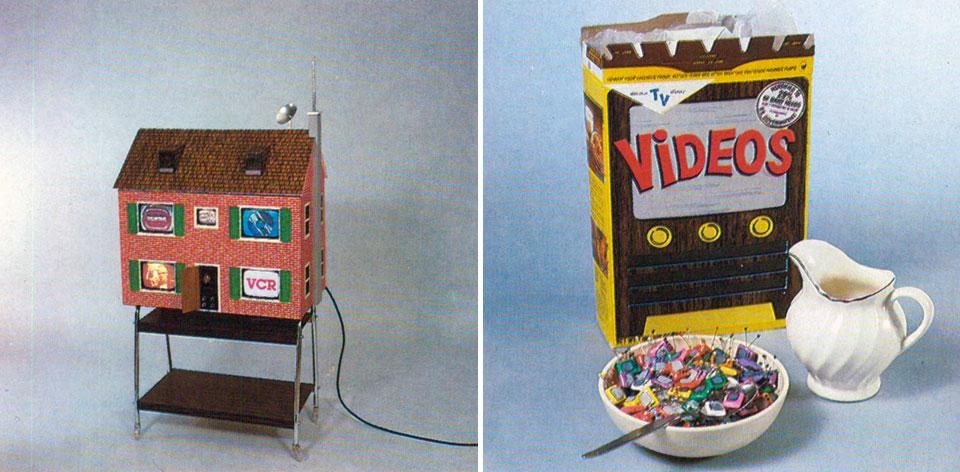

Glancing through Home Video magazine the other day, I came across some designs by Garner for a "new generation" of video machines. It was a pleasant surprise for me to see the creative capacity of this American designer still as active as ever. In the late 60s Garner was already working hard at the design and creation of objects, décors and instruments that might easily have been given the facile label of "radical" or "anti-design".

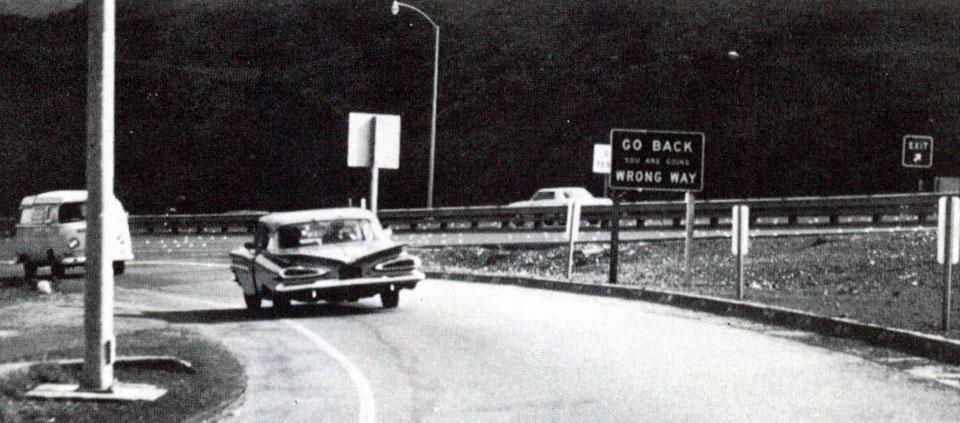

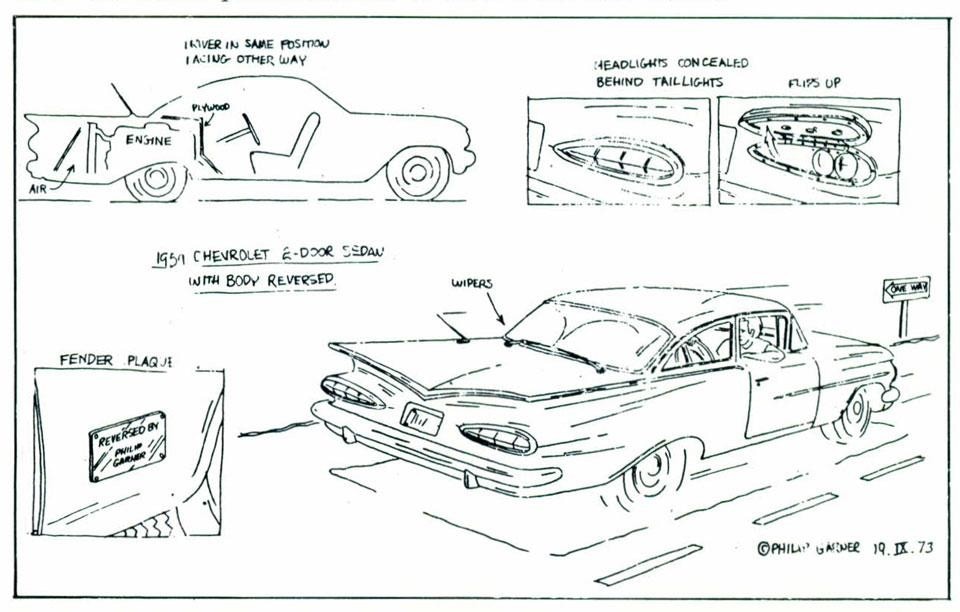

In fact, though Garner's work does have points in common with European radical trends, he stands apart for his declared love of advanced technology. This technological sophistication he applies to amazing works, sometimes ironic, at other times provocative. The Garner of the 60s, then, expressed the crisis of a generation never breaking away completely from the postwar and still existent American utopia of an automatized world.

Garner's designs tell us about a society that cannot be objects alone, but also by articles which forcefully express certain aspects of American society

Garner's designs thus tell us about a society that cannot be objects alone, but also by articles which, unique though they are, forcefully express certain aspects of American society. Ugo la Pietra

It was during my formative years when this phenomenon reached its peak and the images of industrial design and science fiction became almost synonymous. Automation was to produce a world so breathtakingly efficient as to virtually eclipse the ruthless and barbaric side of man's nature. Of course, it was easy for a child, especially one intensely interested in mechanical things and endowed with a certain sense of theatrical style to view this eventuality without skepticism. I soon became the consumate " techno-romanticist".

I feel fortunate to have grown up in post-war America for I don't believe the same situation existed anywhere else in the world or perhaps ever will. Philip Garner