Reconstructing the Teatro Continuo today is not just making up for the harm done – its demolition because of its state of decay in 1989 undermined Burri’s relations with the city of Milan – or paying homage on the 100th anniversary of the artist’s birth.

Reconstructing is always a delicate affair and even more so in the case of a monument as difficult as a theatre, for its past and its future, for the where was it and how was it which usually makes a noise in itself and attracts the inevitable and equally pointless whinging.

Reconstructing is always a delicate affair and even more so in the case of a monument as difficult as a theatre.

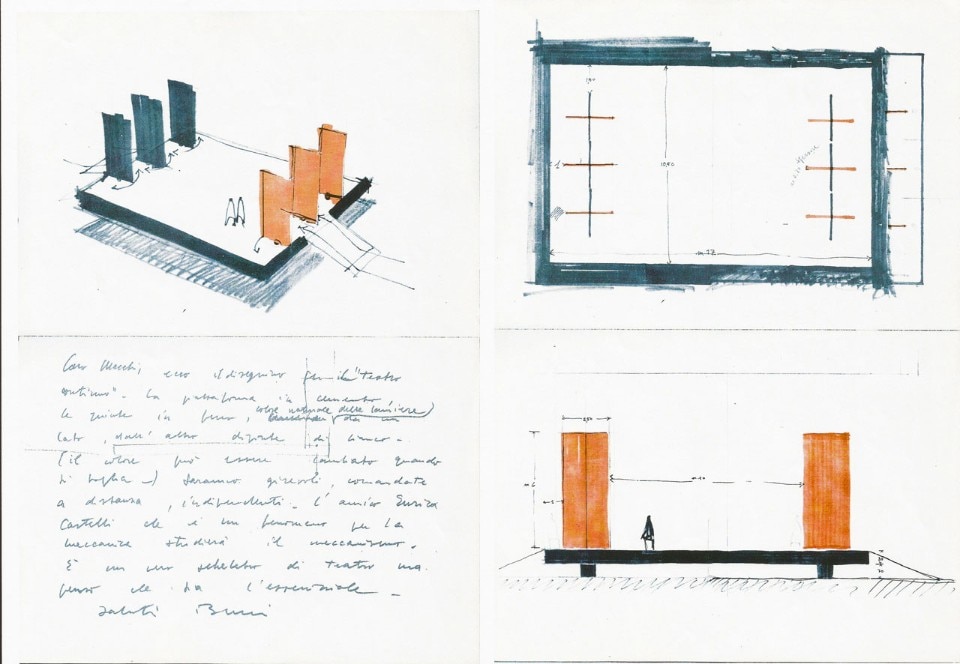

Reconstructing is, in this case, a credible philological action, partly thanks to Burri’s drawings and their consistent simplicity.

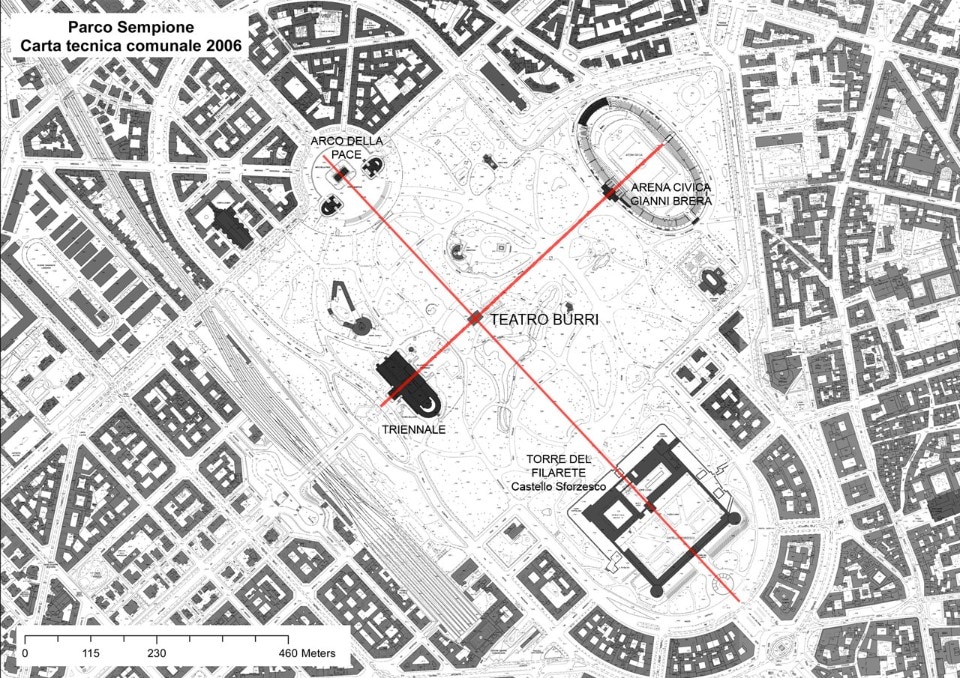

Burri getta il cuore un po’ oltre, facendo del Teatro Continuo il caposaldo e la misura dei tracciati che congiungono l’Arco della Pace con la Torre del Filarete

Reconstructing a work rooted in that place, as much as a piece of the city’s architecture – I wonder whether Aldo Rossi would have accepted this definition. Reconstructing tension for the theatre space, a significant and evocative issue in relation to 20th-century Milanese tradition.

Reconstructing a stage, starting from a void through which the eye can gaze, awaiting the appearance of human figures.

Reconstructing a civil attitude is one of the hidden meanings in the undertaking of Gabi Scardi, an independent curator in charge of NCTM e l’arte.

Reconstructing a civil attitude is one of the hidden meanings in the undertaking of Gabi Scardi, an independent curator in charge of NCTM e l’arte, a contemporary-art project privately sponsored by the NCTM legal practice. The service sector steps in for a country that has applied little more than zero-cost reforms to culture for years.

Reconstructing the work is the task of Bergamo entrepreneur and collector Tullio Leggeri – the only person in the world who could, after formidable wrangles, have created a mock-up for children to climb on and grasp the meaning of Forte Pozzacchio (1914), a huge site-specific or anti-construction work excavated entirely in the rock close to Rovereto. We hope to meet Leggeri on site at the Teatro Continuo between now and March 2015 to pursue these thoughts live.

Basically, what must be reconstructed are one horizontal and six vertical shadow lines; no roof, as Burri did not close it overhead; he did not complete the ancestral shelter. Instead, he virtually took a step back from the familiar work of the architect. Burri left the stars in the sky, without ever naming them.