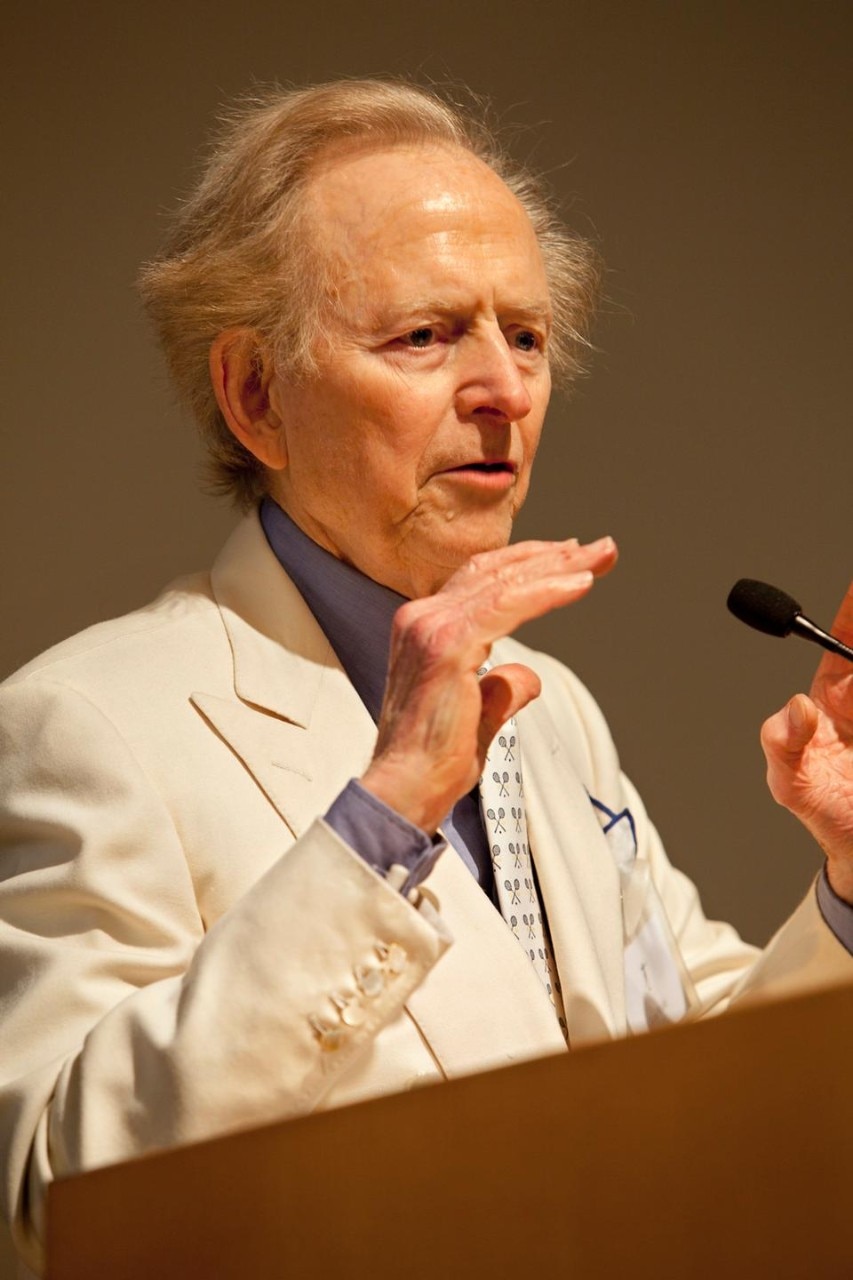

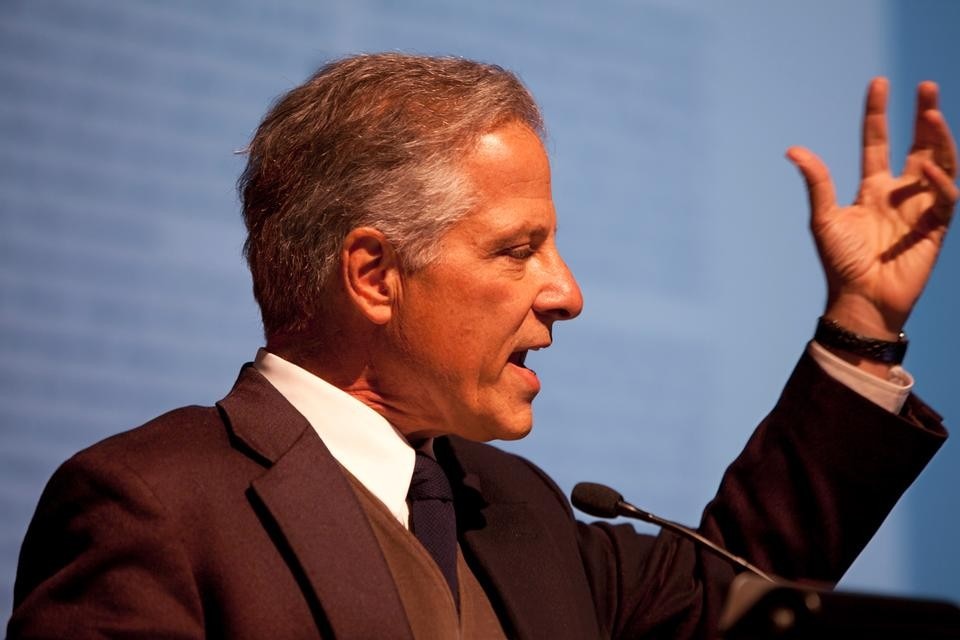

The speakers included a canonical roster of the movement's lead proponents and detractors, from quintessential practitioners of the era (Michael Graves, Robert A.M. Stern, and Andres Duany), to a younger generation of theorists such as Sam Jacob, Emmanuel Petit, and Martino Stierli. Additionally, Jencks, Tom Wolfe, Mark Wigley, Robert Campbell, Witold Rybczynsky, David Schwarz, and others lent first-hand accounts of what happened: the good, the bad, the ugly, the ordinary. The appropriately eclectic list was assembled into a dynamic line-up, with spoilers, teasers, lead-ins, and cliffhangers that enhanced the discussion and kept the discussion moving.

Ironically, the generation gaps that Postmodernism first revealed decades ago were evident at this conference as well, and the lack of representation from the emerging generation of participants and scholars resulted in an event that remained mostly retrospective.

Matt Shaw