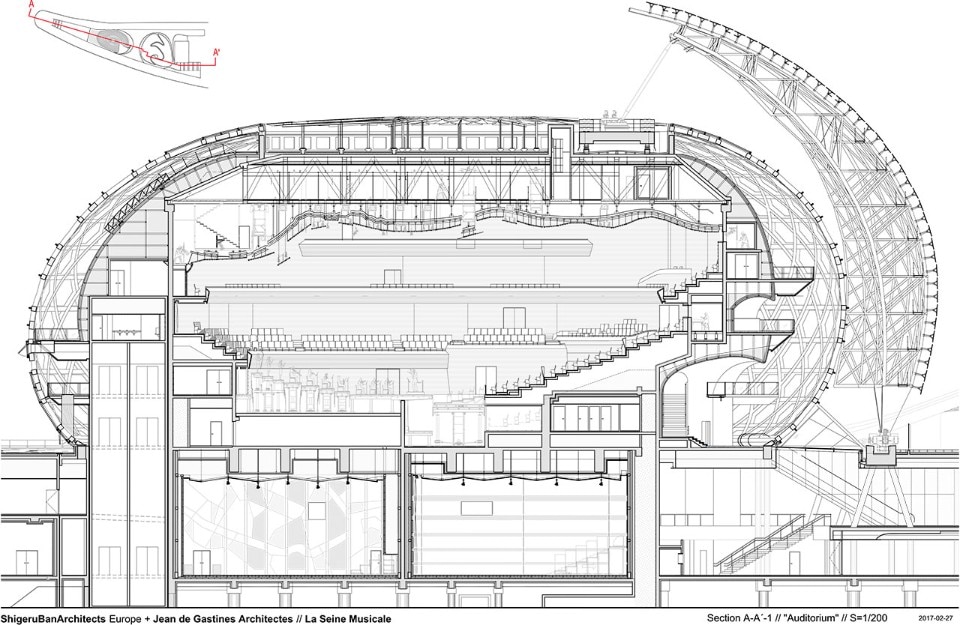

Inaugurated last May on the Île Seguin, La Seine Musicale by Shigeru Ban (with Jean de Gastines) has already gained iconic status. The singular glass, steel and timber shell of the auditorium – affectionately nicknamed the egg – is also a technological masterpiece, clad with photovoltaic cells on moving rails that follow the path of the sun at 15-minute intervals.

However, form, technology and spectacle come very low on the scale of priorities of the Japanese Pritzker prize-winner who has succeeded in the far from easy task of using a humble and inexpensive material such as cardboard to build churches, pavilions and emergency shelters. The Paris concert hall has a capacity of 6,000 and, here too, he used cardboard on the ceiling and walls although “The patterns were created to specific demands by the sound engineers”, he is keen to point out. “They are not simply decoration; they improve the acoustics and the atmosphere.”

Opening up the building to as many people as possible, also when there is no concert on, was another priority. We met him in Paris and asked about his new projects, his concept of flexibility and his love of Europe which, he says, “remains the most interesting place today in which to construct good architecture.”

Salvator-John A. Liotta, Fabienne Louyot: Can you explain how you combine architecture and structure using materials such as cardboard and paper? When did you realise it was possible to build with paper and cardboard?

Shigeru Ban: I have always been interested in structure and materials. I like architects such as Frei Otto who invented their own materials and structures. When I designed one of my first exhibitions, I had to find an inexpensive material for the scenography. Back in those days, we consumed so many paper-tubes, leftover tracing paper and fax paper too. They were stronger than I expected so I started testing them more seriously. I knew that the strength of a building has nothing to do with the strength of its materials. Concrete buildings can easily be destroyed by an earthquake while many centuries-old traditional timber-structured buildings survive in good condition. It takes a lot of money and energy to develop a strong material and the process often requires complex procedures. With paper tubes, I could do the testing myself without the help of structural engineers. In a way, I have developed new applications for something already in existence but with new purposes.

View gallery

View gallery

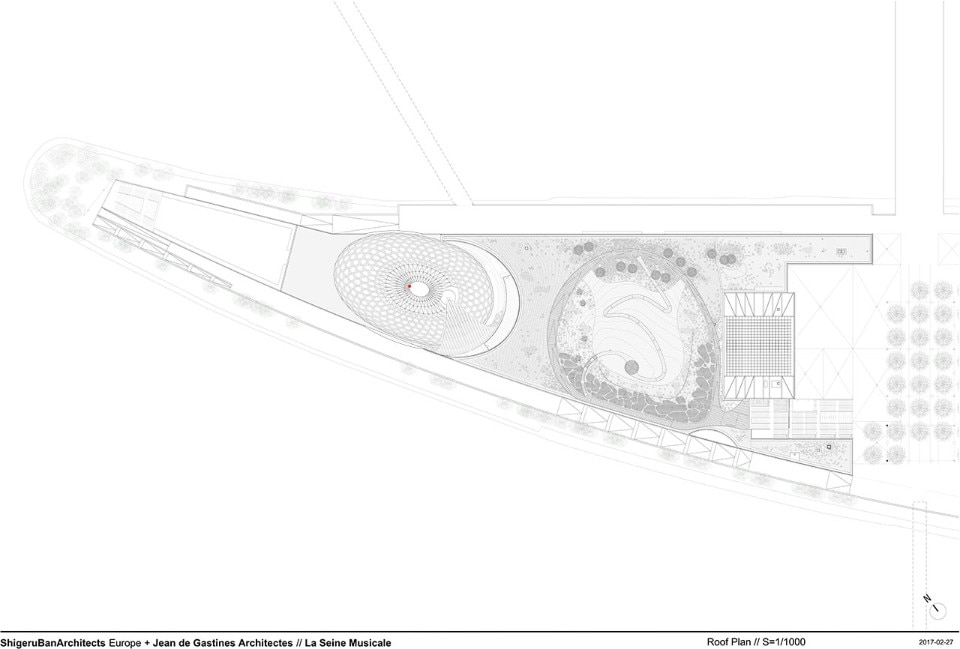

Z:\Projet\CiMu\99_Presse\01_drawings\_Fichiers d'impressions\I-DOCUMENTS GENERAUX\1.2-plans de niveaux\CIMU-PUB-SBA-ARC-PLN-TO-

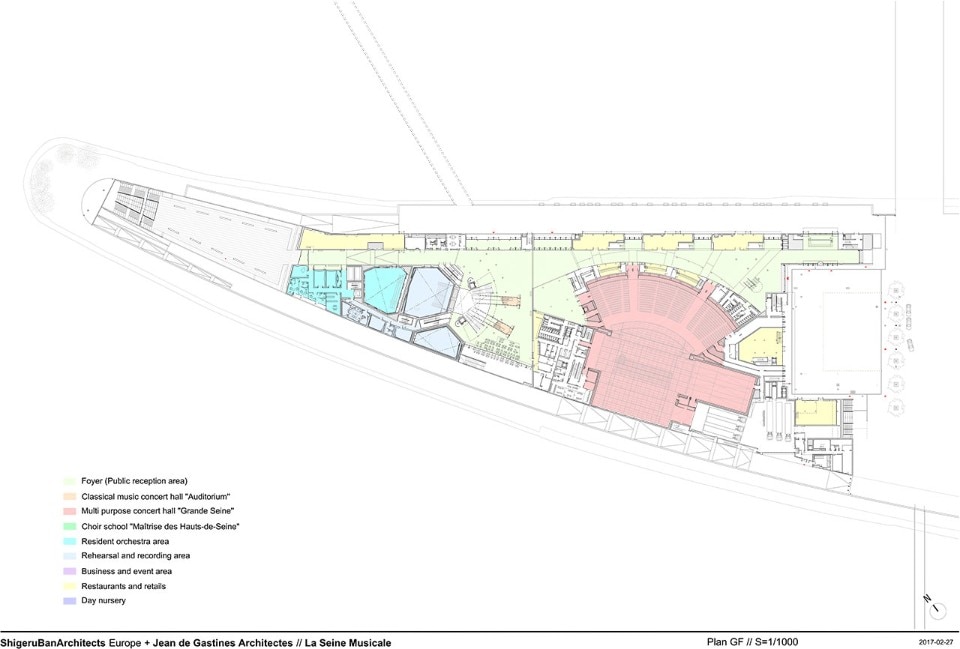

Z:\Projet\CiMu\99_Presse\01_drawings\_Fichiers d'impressions\I-DOCUMENTS GENERAUX\1.2-plans de niveaux\CIMU-PUB-SBA-ARC-PLN-N0-

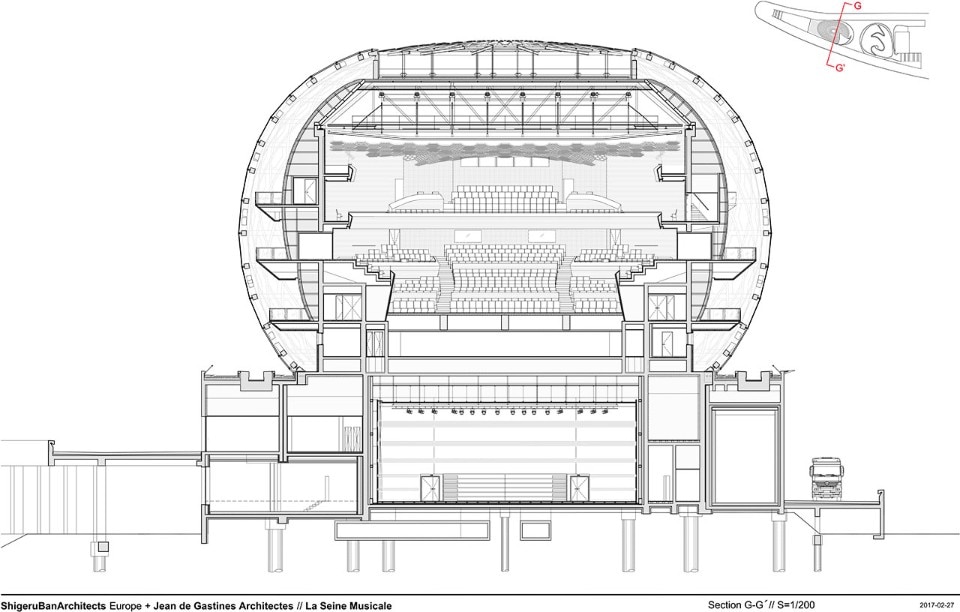

Z:\Projet\CiMu\99_Presse\01_drawings\_Fichiers d'impressions\I-DOCUMENTS GENERAUX\1.3-Coupes\CIMU-PUB-SBA-ARC-COU-GG'-ZB G-G (1

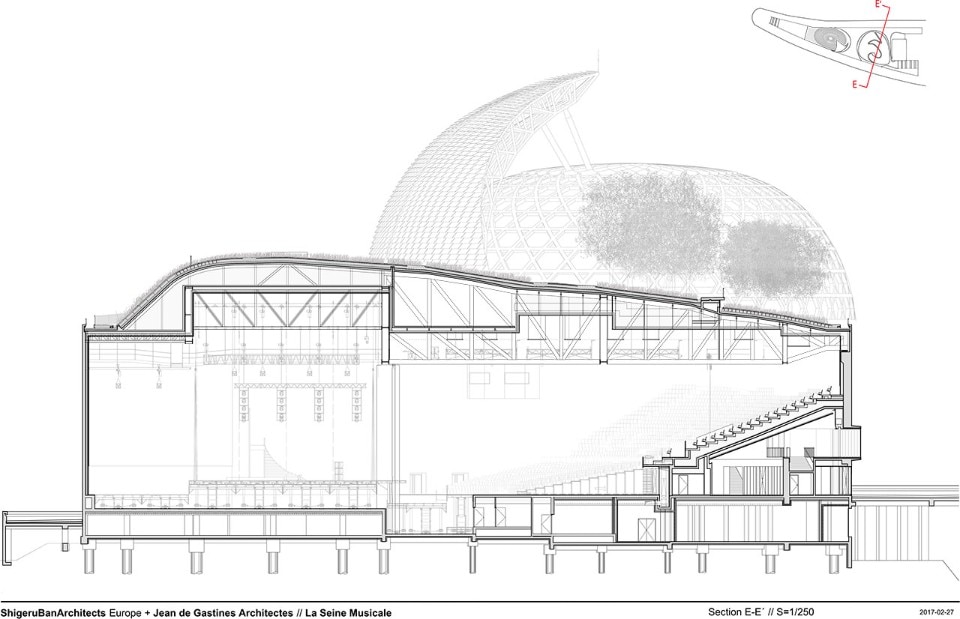

Z:\Projet\CiMu\99_Presse\01_drawings\_Fichiers d'impressions\I-DOCUMENTS GENERAUX\1.3-Coupes\CIMU-PUB-SBA-ARC-COU-EE'-ZA E-E (1

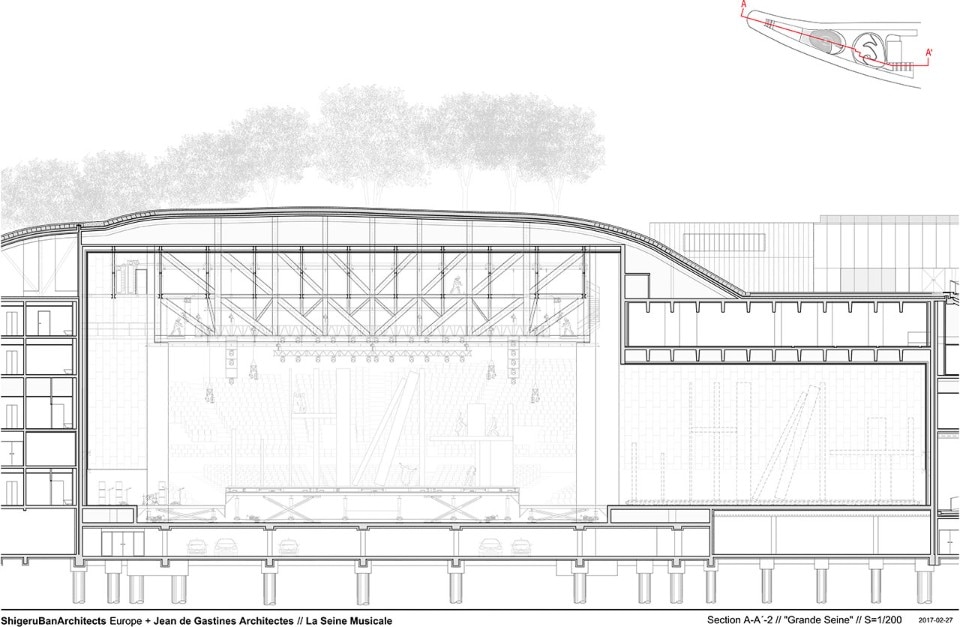

Z:\Projet\CiMu\99_Presse\01_drawings\_Fichiers d'impressions\I-DOCUMENTS GENERAUX\1.3-Coupes\CIMU-PUB-SBA-ARC-COU-AA'-TZ A-A Gr

Salvator-John A. Liotta, Fabienne Louyot: The main Hall of La Seine Musicale is a latticed timber structure that brings great character to your architecture. Inside, you employed a lot of cardboard for the seats, walls and ceiling. Can you tell us more about your use of patterns in the structure and decoration?

Shigeru Ban: The dome has an interlaced curved timber structure. The hexagonal pattern I adopted for the dome of La Seine Musical is the only one that allows just two elements to meet and join, so the connection is simple. The patterns on the walls are based on acoustic demands from the engineers. This ceiling is very unusual. I cannot deny that the decoration creates different patterns and shadows, and so different moods depending on the show and scenery. It’s not just mere decoration.

View gallery

View gallery

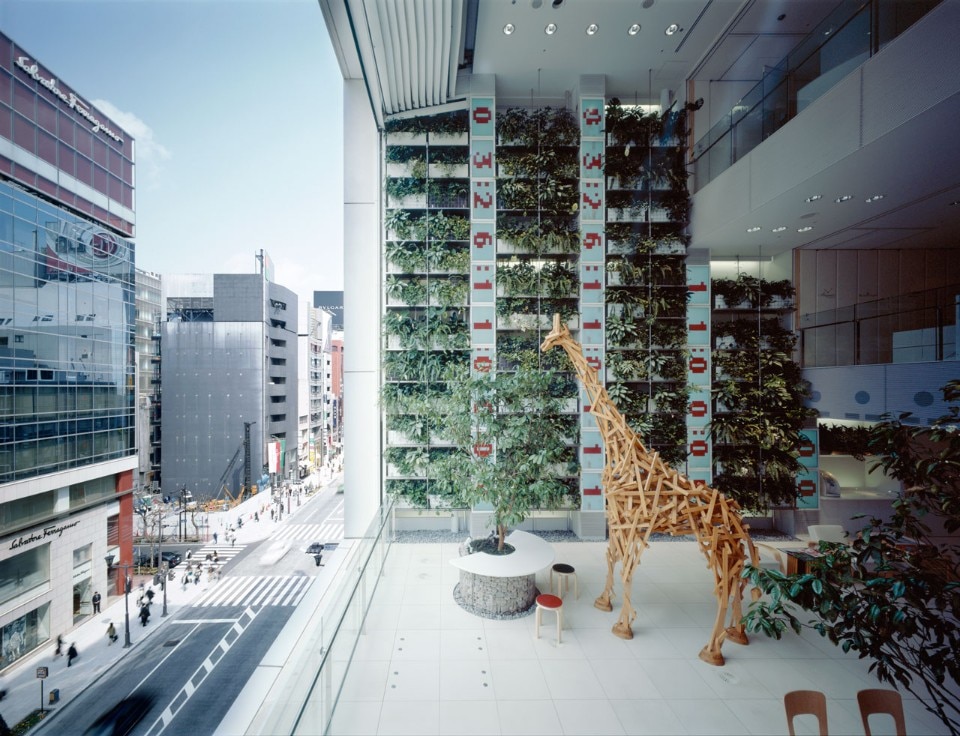

Salvator-John A. Liotta, Fabienne Louyot: In your Glass Shutter House (Tokyo, 2003), Metal Shutter House (New York, 2010) and Hayek Centre (Tokyo, 2007), you used a system of openings that transform the interior of the building into an intermediate space, an atypical public space. It is a private but public space. You adopt a similar solution in La Seine Musicale. What is the concept behind this openness?

Shigeru Ban: I feel that no matter what the type of person, an intermediate space is a more enjoyable one. People love having coffee in Italian cities and in Paris and, when it is not possible outside because it is cold, an intermediate space means people can still enjoy it. So far, I have used shutters, folding doors and other different ways of opening a space to connect the inside and outside but it is really all about adjusting the scale of the openings to public use. I also feel it’s important to open a building up to the outside because normally theatres only attract a certain kind of person. I think public buildings must be more open to the public, including poor people. In this sense, intermediate spaces grant free access to public buildings so that people can enter and just stroll around. By doing so, everyone can absorb something of the culture breathed inside. In the case of La Seine Musicale, I had to respect Jean Nouvel’s masterplan. That’s why I decided to extend his shopping street through the entrance to the end of my building. Once opened, the huge shutter lets people walk along a public promenade that brings the outside into the building. Theatres are usually closed when there are no concerts on but I wanted to make the building open to the public and let them come in all the time. Once inside, you can see the rehearsals and concert hall through the big windows along the promenade. It’s a very interesting and unusual experience.

View gallery

View gallery

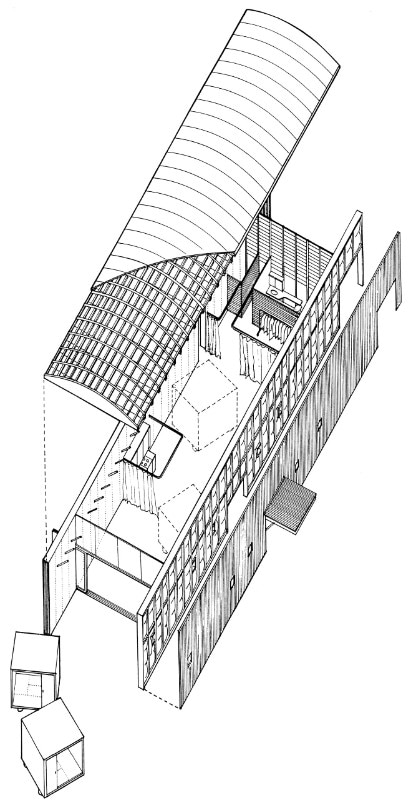

Salvator-John A. Liotta, Fabienne Louyot: Flexibility is recurrent in your projects, such as when you put rooms/cubicles on wheels for the Naked House (Saitama, 2000), allowing the space to be reconfigured for different project needs. We are also thinking of your project for a summer house without walls.

Shigeru Ban: In both cases, the idea came from the fact that the clients had a very limited budget and little space. Creating a flexible space with different superimposing functions is a way to improve small spaces and make the most of a restricted budget. All this results in a very interesting final design. I always look for problems over and above budget, site constraints and regulation, and try to solve them with design.

View gallery

View gallery

Salvator-John A. Liotta, Fabienne Louyot: In one of your best-known projects – the Curtain Wall House – we sense your experimentation with Japanese and Western ways to create space. On the one hand, there is a dissipation of the boundaries and, on the other, the use of a dual-height curtain. How did you come up with this idea?

Shigeru Ban: It may be that I am unconsciously influenced by the Japanese culture but, in general, I don’t like critics to link my design to it. For the Curtain Wall House, I was strongly influenced by Californian houses I visited when I started studying architecture in USA. There, they use simple or industrial materials and, because of the dry climate, they try to open the house up as much as possible, something I kept in mind. The dual-height curtain in my project is a shading device like those you might find in Piazza San Marco, Venice, Italy. I remember that, after going to Beirut, I was surprised to see how many balconies have big curtains for shade. In a sense, it’s very similar to my concept.

Salvator-John A. Liotta, Fabienne Louyot: How did you decide to work in France and why? What are the differences between France and the other countries where you work (including USA and Japan)?

Shigeru Ban: I decided to open an office in Paris in 2004 when I won the competition for the Centre Pompidou-Metz. I thought this project was hugely important for my career and I didn’t want to make any mistakes. I wanted to control the whole process myself. I had never designed a museum before when I won the Centre Pompidou competition and I had never designed a theatre when I won La Seine Musicale competition. This would never happen in Japan or USA. In France, clients are looking for interesting ideas and design. I commute between Tokyo and Paris every week but I’m enjoying it. It’s part of my training. Working in Japan, USA and Europe is very different. Japanese contractors are very supportive and we have excellent manufacturing but, being an island, it is difficult to attract different types of brilliant consultants and manufacturers from Europe. USA is the most difficult area because all the manufacturing has gone. If you don’t have a big budget, everything has to come from China. Europe is the best place because there are many manufacturers and engineers. Sourcing high quality materials from Italy or Finland is easy. You can take advantage of the open market so that is why I think Europe is the most stimulating area for making interesting architecture. When I opened my office in Paris, I brought staff from Tokyo but, after a while, I hired locally. I also have a very good French partner: Jean de Gastines. I feel very lucky.

View gallery

View gallery

Salvator-John A. Liotta, Fabienne Louyot: You have produced several humanitarian projects. Can you tell us a little about what drives you to engage with this area?

Shigeru Ban: After spending 10 years practising architecture, I wanted to use my experience and knowledge not only for the privileged but also the general public, people who have lost their home in a natural disaster. There are always many new opportunities for architects after tragedies. I knew that people endure harsh living conditions before the rebuilding process so, as an architect, I wondered how I could improve living conditions or evacuation facilities with temporary housing before people return to normal life with the proper facilities. That’s why I decided to use cardboard partitions, to give people some privacy back. Privacy is a basic human need and intimacy is essential for our mental health. After a disaster, people experience the loss of their loved ones, personal wealth and belongings; being obliged to share their space with strangers is really too much. That’s why I did it.

Salvator-John A. Liotta, Fabienne Louyot: What is your architectural message to the world?

Shigeru Ban I don’t have a message to the world but I always tell young students that they must travel and experience different cultures. That's the most important starting point if you want to become a good architect.

Interview by Salvator-John A. Liotta and Fabienne Louyot

© all rights reserved