Anja, the protagonist of Oval, which is a science fiction novel written by Elvia Wilk and recently published in Italy by Zona 42, lives on The Berg.

In the fiction of the book, The Berg is an artificial mountain built on what is left of Tempelhof airport [1]. The Berg is an eco-friendly, zero-emission community run by the multinational corporation that controls the city and lives of the protagonists. The Berg is a rotting nightmare of inefficiency, malfunction and disruption. The Berg is a carbon neutral dystopia, overshadowed by the Green New Deal. It is ecology without any criticism of the production system – basically, it is gardening. Or rather, its urban equivalent.

Even in the world created by Wilk – which is our world, just a few minutes in advance – the ecological transition, or rather, the collection of practical recipes that should help us overcome the climate crisis we are experiencing, is irreparably compromised and lessened in the context of capitalist realism. What is presented to us as a solution in the renderings, statistical projections, and politicians’ speeches, turns out to be only one of the many dystopian futures among which we can choose. This should not surprise us. We live in such a problematic reality that dystopia is what best defines the mood of the visions of the future produced by our culture: whether it be cyberpunk, steampunk, or climate science fiction, our ability to imagine what awaits us is dominated by gloomy visions imbued with pessimism.

Solarpunk is an exception to this rule. Coming from the outermost nooks and crannies of the internet, it is a complex and multifaceted cultural artifact and, at the same time, a literary subgenre of the already mentioned climate science fiction; an aesthetic in which nature and technology maintain a balanced, mutually beneficial relationship; a movement of criticism of the current social and economic structures that, precisely through the harmony between nature and technology, are planned to be overcome in ways that we can easily describe as utopian.

Therefore, Solarpunk employs the ideas linked to the need for a return to utopia as a strategy to imagine, visualize and design a future capable of breaking with the meaning frames that define the mood of the era in which we live.

History and origin of solarpunk

To find the first occurrence of the term “solarpunk”, we need to go back to twelve years ago, to an article called From Steampunk to Solarpunk published in 2008 on Republic of the Bees, an economics and politics blog that pays particular attention to a couple of themes: the solar transition and the theory and practice of common goods. In the article, which talks about the launch and maiden voyage of the Beluga Skysail, the first contemporary cargo ship to use sail power to reduce fuel consumption, a new literary genre, Solarpunk, is hypothesized for the first time.

The best way to describe it, says the author, is by contrasting it to steampunk: “it conflates modern technology with older technology, but with a vital difference. In the case of steampunk, the focus on Victorian technology serves as a guideline for imagining an alternative world. In the case of solarpunk, the interest in older technologies is driven by modern world economics: if oil isn’t a cheap source of energy anymore, then we sometimes do best to revive older technologies that are based on other sources of energy, such as solar power and wind power.”

Moreover, the author of the article in Republic of the Bees says that another difference between the two genres is that “solarpunk ideas, and solarpunk technologies, need not remain imaginary, and I indulge a hope of someday living in a solarpunk world”.

Ever since its first occurrence, solarpunk has had the ambition to be much more than just a literary genre, an aesthetic or an imaginary. Solarpunk is, essentially, an exercise to visualize the future, an instruction manual to redesign the reality that has found in the internet its ideal breeding ground and vehicle. Its objective, as Elvia Wilk points out in Is Ornamenting Solar Panels a Crime?, her analysis of the genre published on e-flux, is to “transform science fiction into science action”. The way in which solarpunk tries to pursue this goal contributes to defining its political dimension. But what is the latter characterized by?

Solarpunk’s political dimensions

One of the elements that best defines solarpunk is its speculative nature. That is, as we have already pointed out, the effort aimed at designing a world in which prosperity, peace, sustainability and beauty are not just hopes, but also an achievable goal, within the reach of an organized movement capable of transforming its criticism of the existing into concrete actions. This is the definition given by Andrew Dana Hudson, in a long essay published on Medium called On the Political Dimensions of Solarpunk, whose subject is precisely the political implications of this genre.

Dana Hudson believes that “barring radical cataclysm, the reasonably inevitable trends of urbanization, an aging populace and climate change will set the stage for life in the coming five decades. If you are a human living in the middle of the 21st century, chances are you will be elderly — or surrounded by the elderly. Chances are you will live in a city. Chances are your community, country and supply chains will be plagued by some combination of extreme weather, rising sea levels and droughts”.

True to its “punk” nature, Solarpunk’s task is to oppose the political domination of the old, even though it is fully conscious of having to live with it. Therefore, since architecture and infrastructure are two key elements of solarpunk aesthetics, aiming at a coexistence between generations means designing them to be sustainable in the long term and flexible enough to meet the needs of very different people. This will also entail the need to accordingly reorganize the forms of communal living, adapting them to the evolving climate context as well as to the necessary new urban organization. The attention will therefore focus on the dimension of mutual economic exchange, on generative and procedural political practices, on modular, light and open source ways of communal living. This perspective is very similar to the idea of curing the planet from an infection, a necessity that is well formulated by Donna Haraway in the first paragraphs of her Chthulucene, stating how it is necessary “to be present in the world as interconnected mortal creatures in a myriad of open configurations made up of places, ages, questions and meanings”.

However, just like in Haraway’s texts, all the effort put in by solarpunk is fully conscious of the fact that redesigning the world will only be made possible with a bottom-up push. The landscape will therefore be dominated by scattered and connected communities, which will rise side by side with realities dominated by other ways of managing the existing. In its political dimension, solarpunk does not aim at imposing a global order, but rather at determining a net of connections and relationships that, as Haraway says, will allow us to “live and die together with each other” and which will be possible to access only by accepting the rules and customs, changing them accordingly.

In the path towards this political, imaginary and aesthetic project, they take on a crucial role.

Images to remake the world, the aesthetics of solarpunk

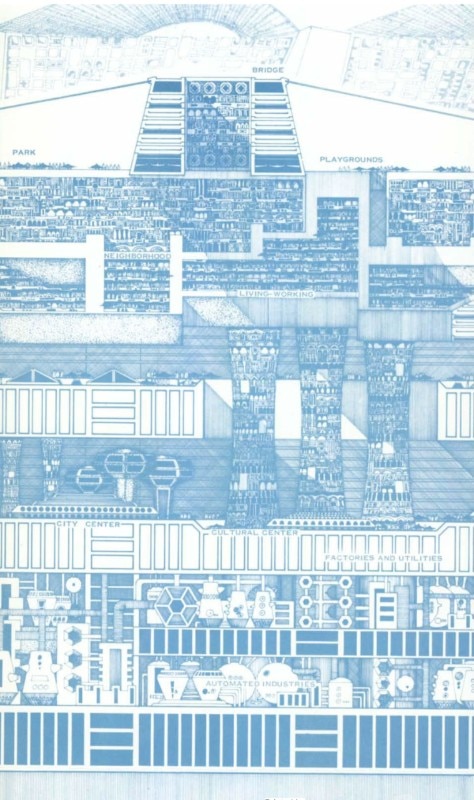

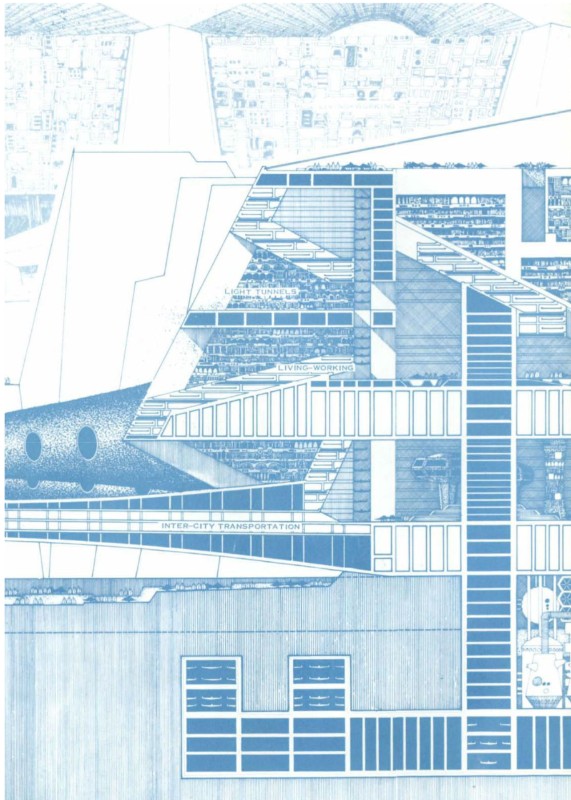

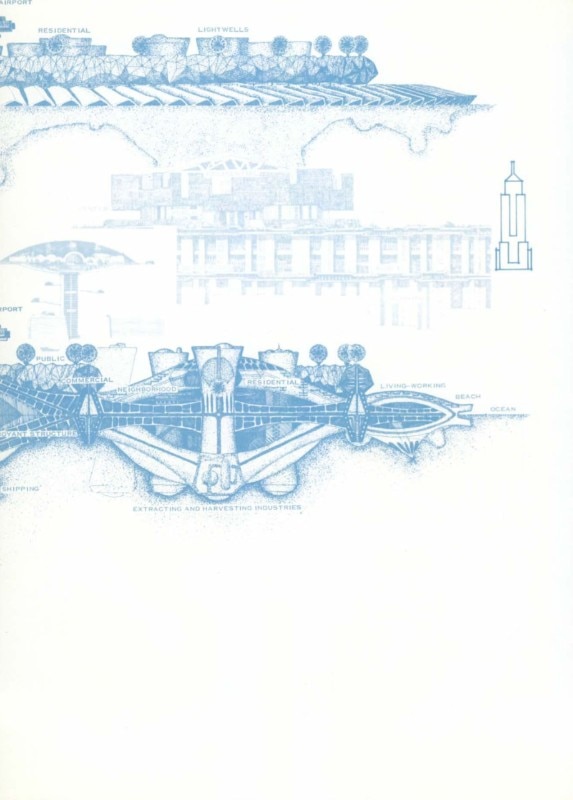

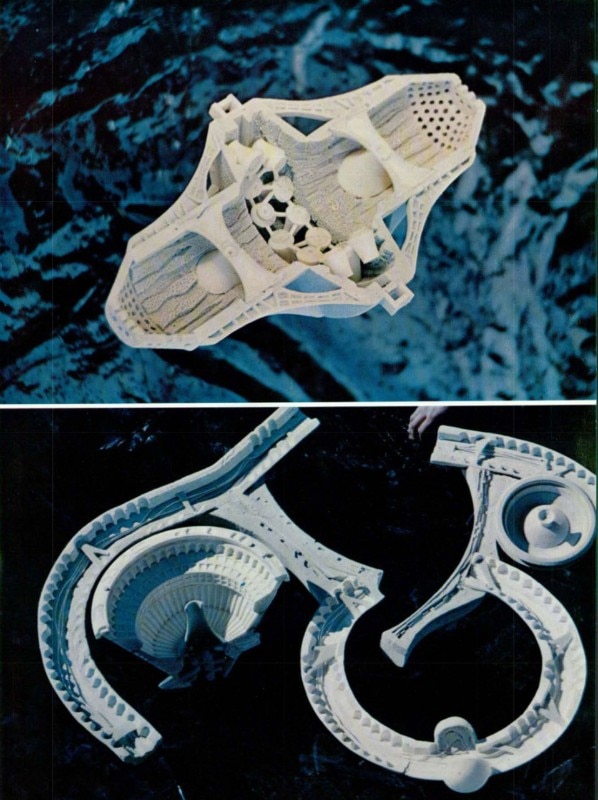

Solarpunk aims at becoming a movement that can regenerate the reality, and offer solutions to the challenges that characterize our age – the rapidly aging population, the ever-increasing urbanization and climate change. In doing so, it shows an attitude towards the recovery of disused technologies and their integration with more contemporary ones, as well as fostering a more general harmony between technology and nature. These characteristics can also be found in the complex aesthetics of the movement. We could say, if we wanted to define its extremes, that it is located in a visual spectrum between explicit references to art nouveau and direct references to the more contemporary biophilic design.

Between these two extremes, we find glass and metal architectures, greenhouses and winter gardens that serve as an ideal counterpoint to the glass and concrete fortresses that dominate the visual horizon of cyberpunk metropolises, whose blunt opacity is opposed by airy transparencies reminiscent of Islamic architecture. It is in these spacious volumes that, filtered by the green of the plants and the blue of the water, sunlight penetrates, caressing solar panels and ornamental wind turbines.

Everything shines with subtle emerald and aquamarine nuances. The air is clean, fresh and breathable. Everything seems surrounded by a faint halo of humidity, as if people were floating in a cloud of water mist. The atmosphere is reminiscent of the evocative universes of Hayao Myazaki’s movies – in fact, he is one of the most cited aesthetic references when talking about solarpunk and its aesthetics. An aesthetic that covers every aspect of the world and life. Decorations, ornaments, clothes and jewelry, everything fits this hybrid style, where ancient and hypermodern blend into each other.

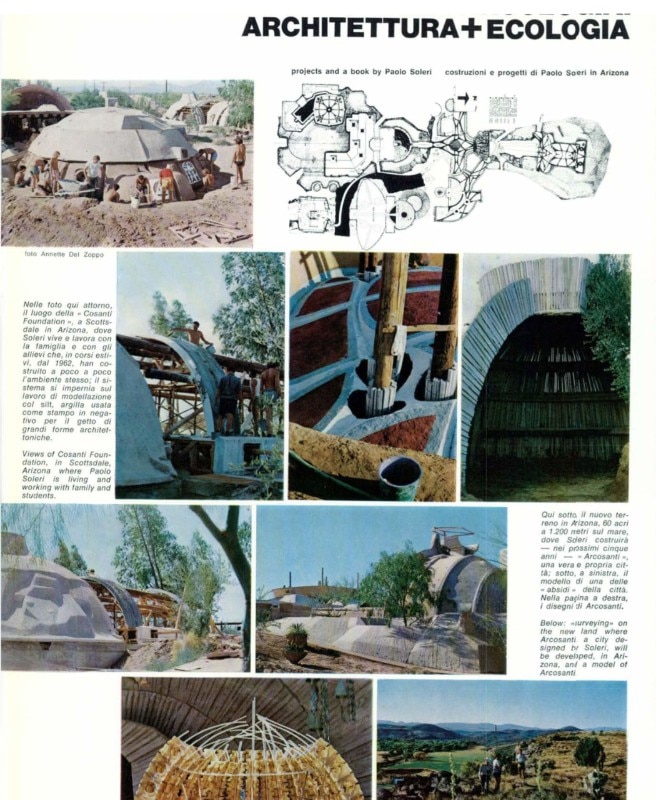

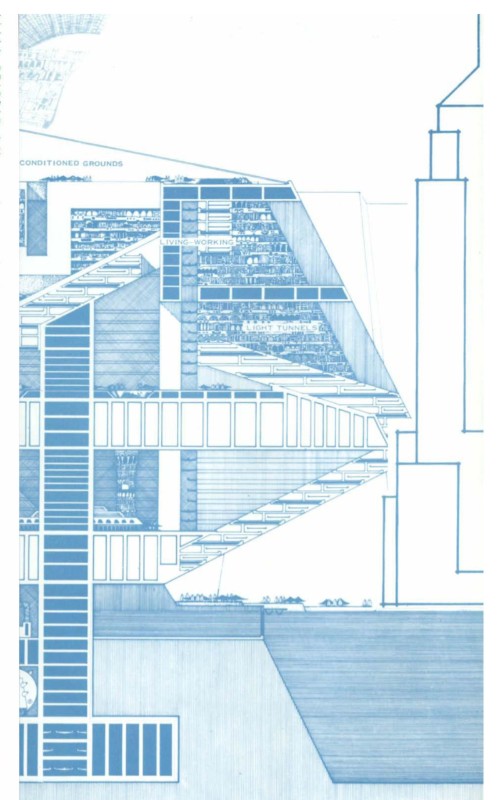

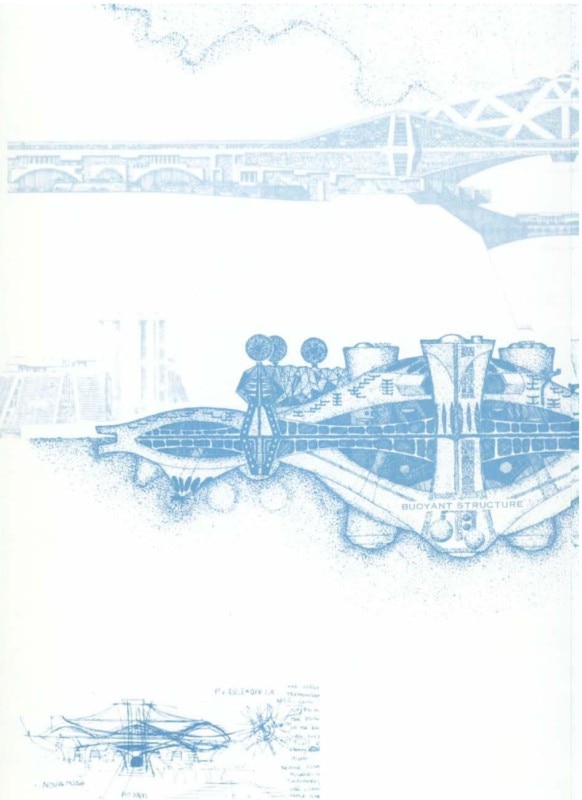

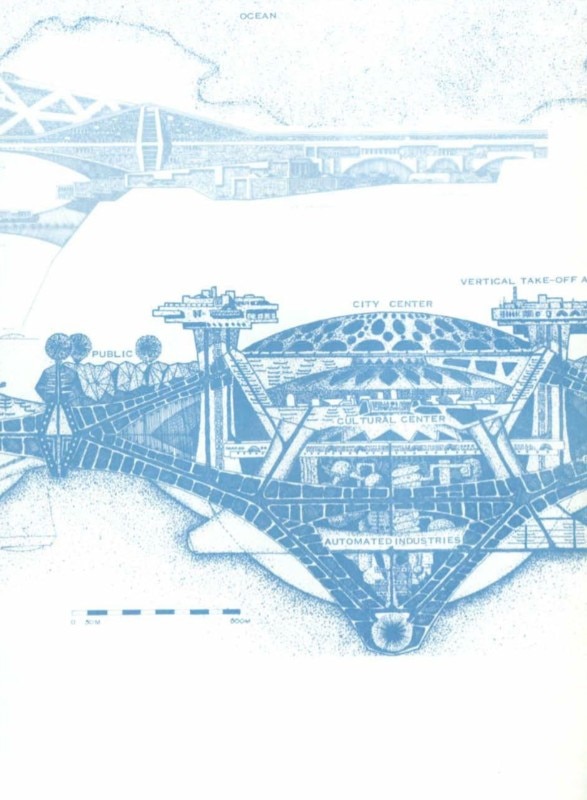

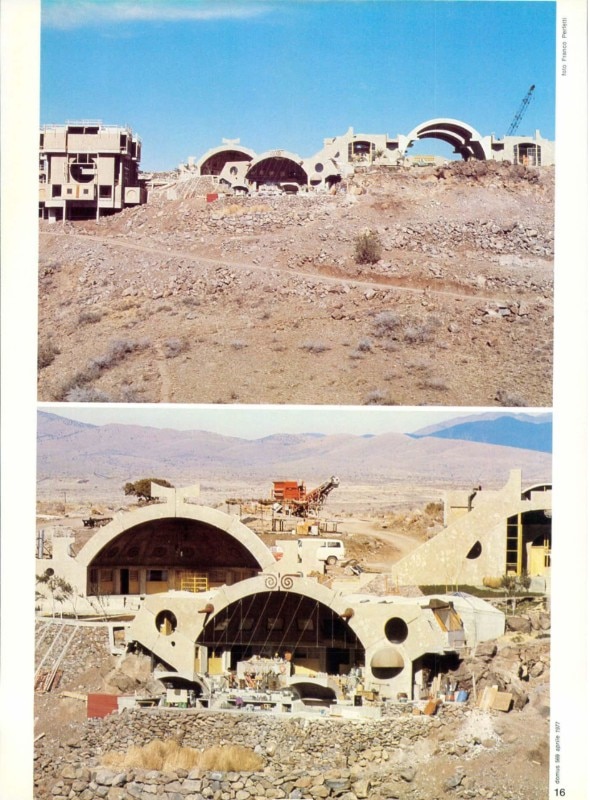

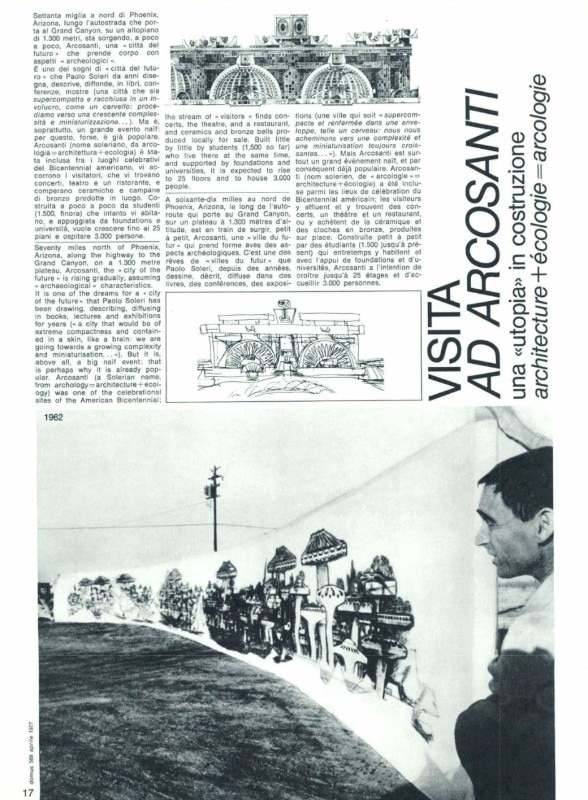

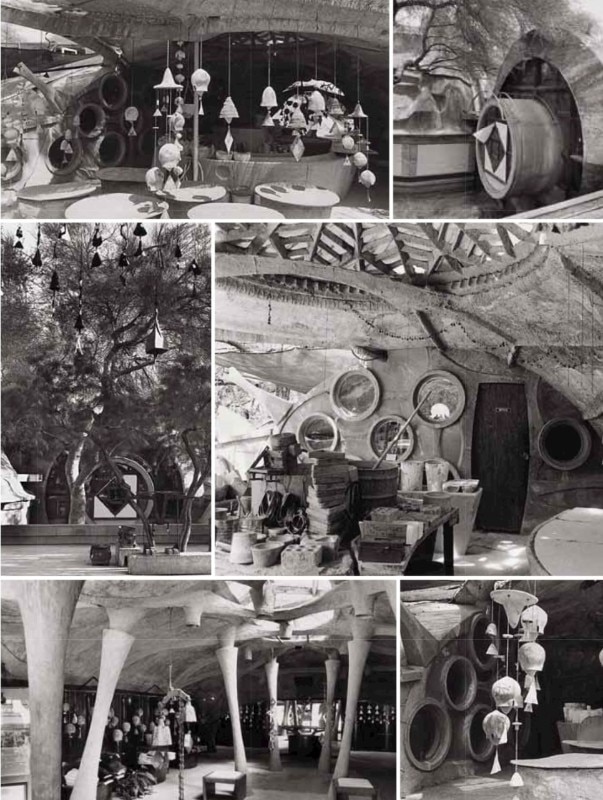

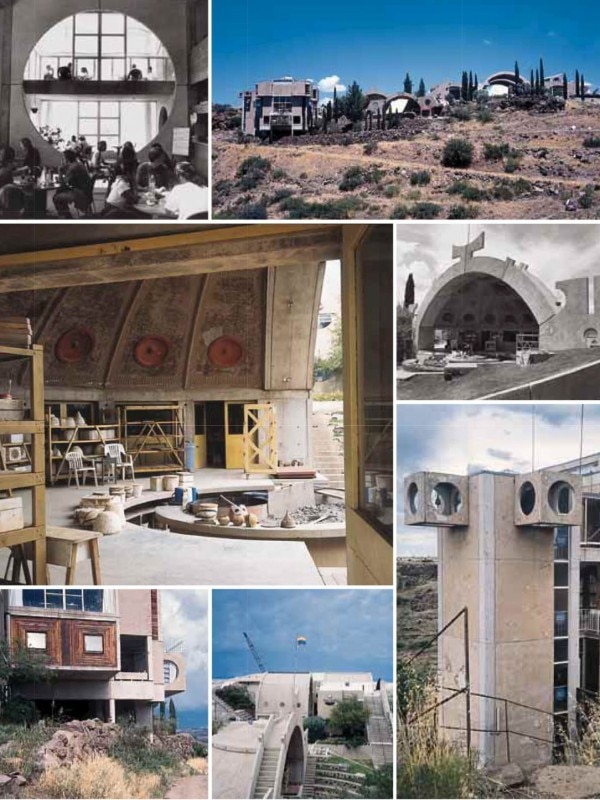

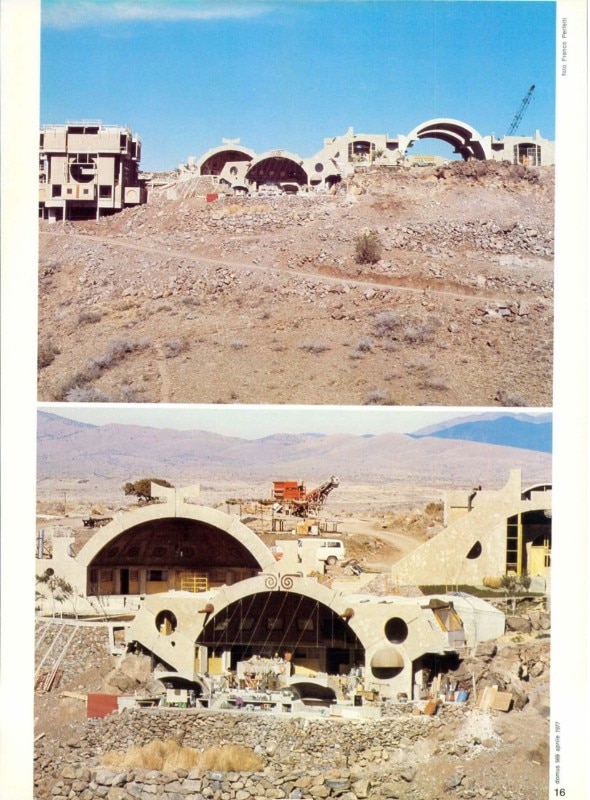

This fusion of different times – which means that the city of Arcosanti, a prototype arcology built under the supervision of Paolo Soleri in 1970 in Arizona, can also be interpreted as an effect of the disarticulation of the sense of time brought about by the spread of digital technologies. As Aaron Z Lewis notes in The garden of forking memes, an essay recently published on his blog, “The internet has flattened the vast archive of the past and made history unprecedentedly (and unrelentingly) immediate”. This flattening has resulted in fracturing our collective experience of time. Internet therefore appears to us as a vast surface on which, while surfing, certain whirlpools can drag people under the surface, into the less illuminated depths of the net, along endless funnels of meaning that redefine the subjective experience of reality, bending it until it is reconstructed, to make it real.

With its Tumblr posts, its Pinterest boards, its Telegram or Discord groups and its Instagram hashtags, solarpunk is one of the many whirlpools you may come across along the way. This is where its greatest strength lies. Slipping into one of these semiotic vortexes can lead to redefine the subjective experience of reality that – as opposed to the collective elaboration of the imaginary, with the production of memea, sense and knowledge – is curved until it is reconstructed. As a consequence, the objective of redesigning the reality appears no longer as a hope or a wish, but rather as an attainable horizon, within the reach of a movement that, after having elaborated its own policy, must only realize that it has the necessary strength to impose its vision and learn how to exercise it.

- [1]:

- Located in south-west Berlin, between the districts of Neukölln and Schönberg, Tempelhof Airport covers 386 hectares. In 2001, it was transformed into a public park, the largest in the German capital. From June 26, 1948 to May 12 of the following year, it was used as an airstrip for the Berlin Airlift, the operation by which the United States and their allies supplied West Berlin, at the time surrounded by Soviet troops