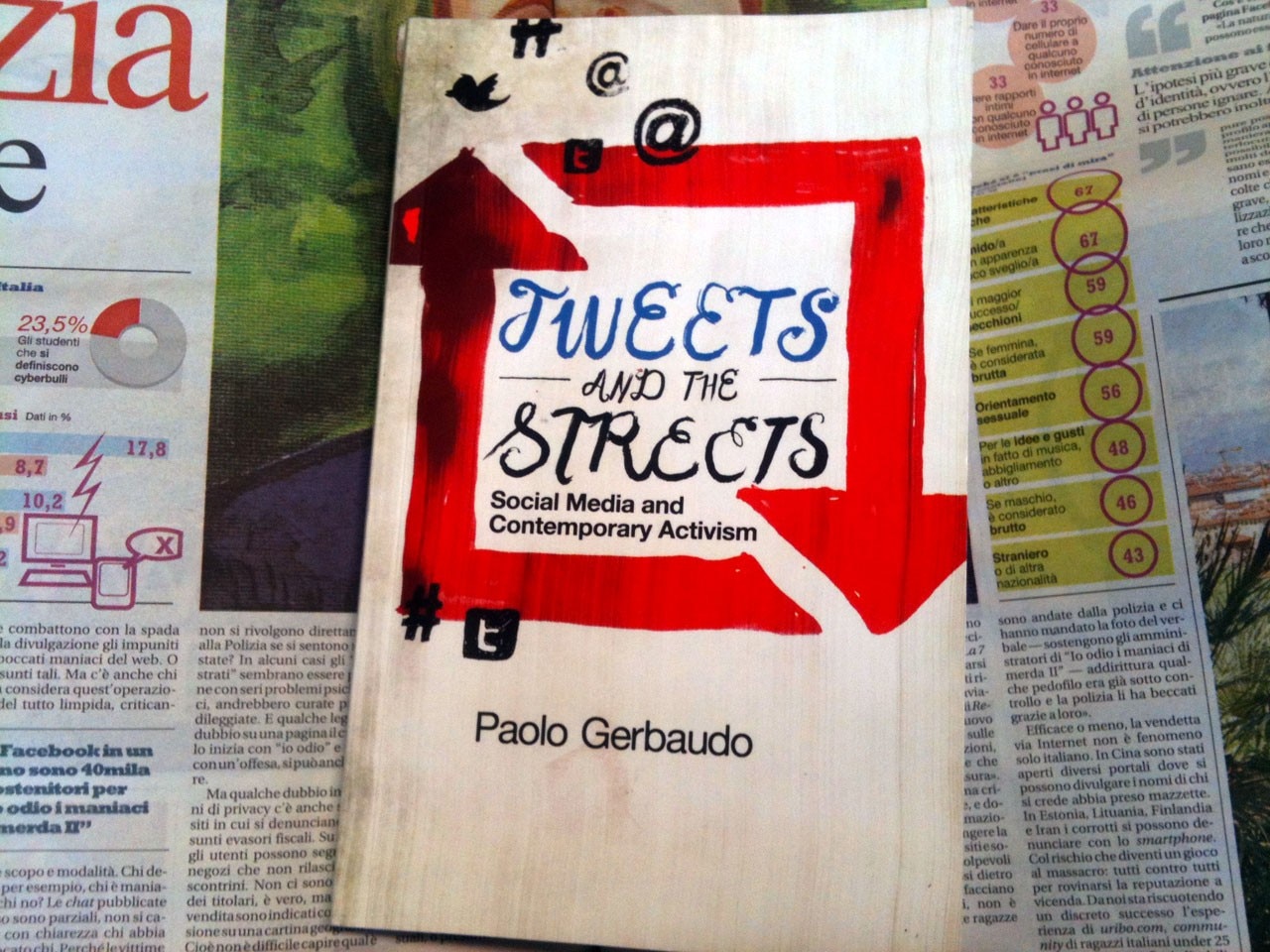

Paolo Gerbaudo, Tweets and the streets. Social media and contemporary activism, PlutoPress 2012 (pp. 208; €17.50)

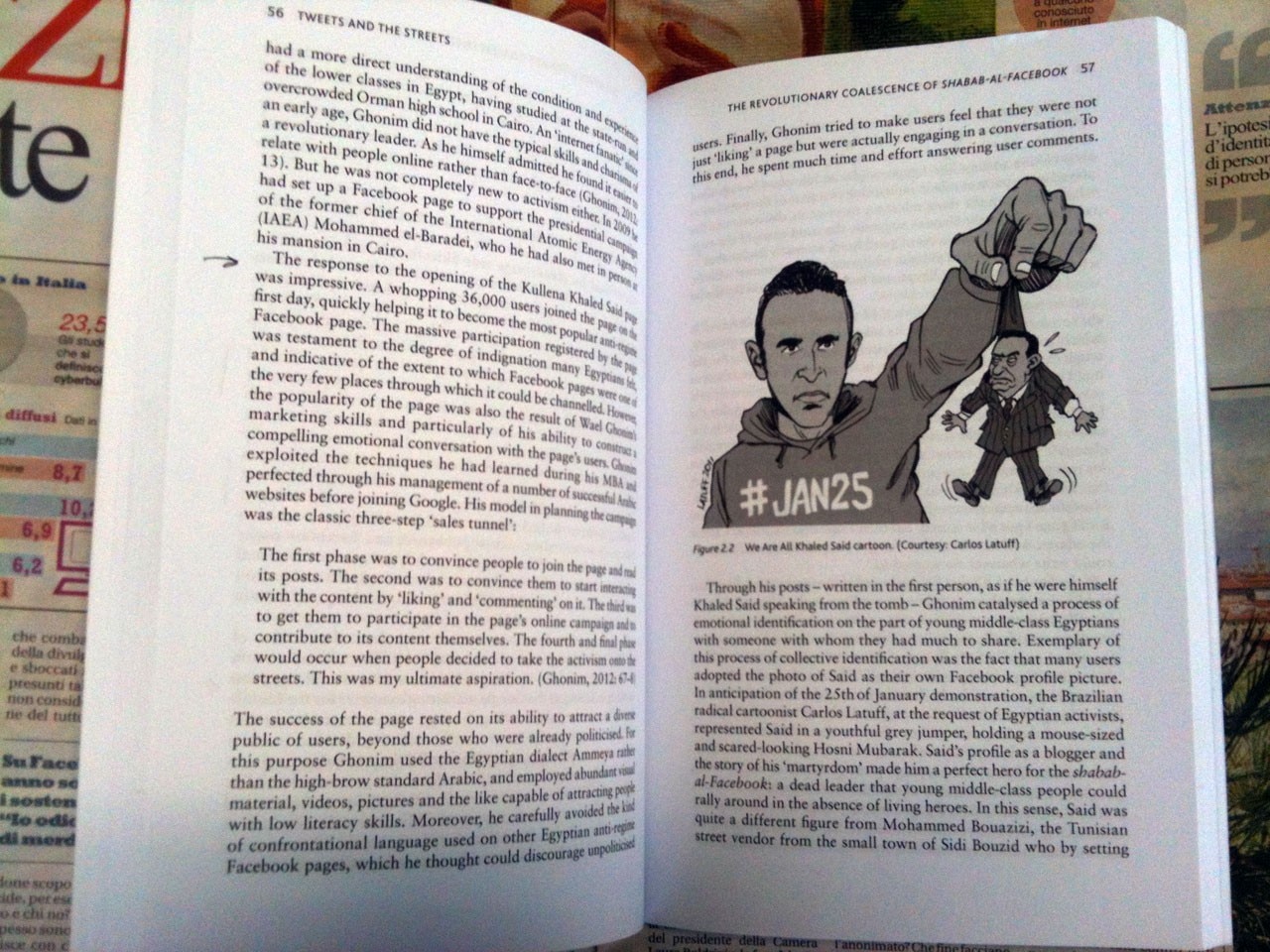

On 6 June 2010, Khaled Said, a 28-year-old Egyptian man, was taken by police from an internet café in Alexandria, where he had been updating his blog, and brutally killed. The image of his mutilated face began to circulate on the web, provoking discussion, comments and articles. The violence of Mubarak’s regime was fiercely criticised: “It could have been me” hundreds of young, middle-class Egyptians started to think. Wael Ghonim, a 30-year-old Google employee, created a Facebook page called “We are all Khaled Said”. In the space of a few days it had over 36,000 followers, making it the country’s most popular anti-regime page. It was the start of the revolution, a roll of the dice by the “Facebook generation” (shabab-al-facebook) that aimed to transform the outrage of the comments into real protest.

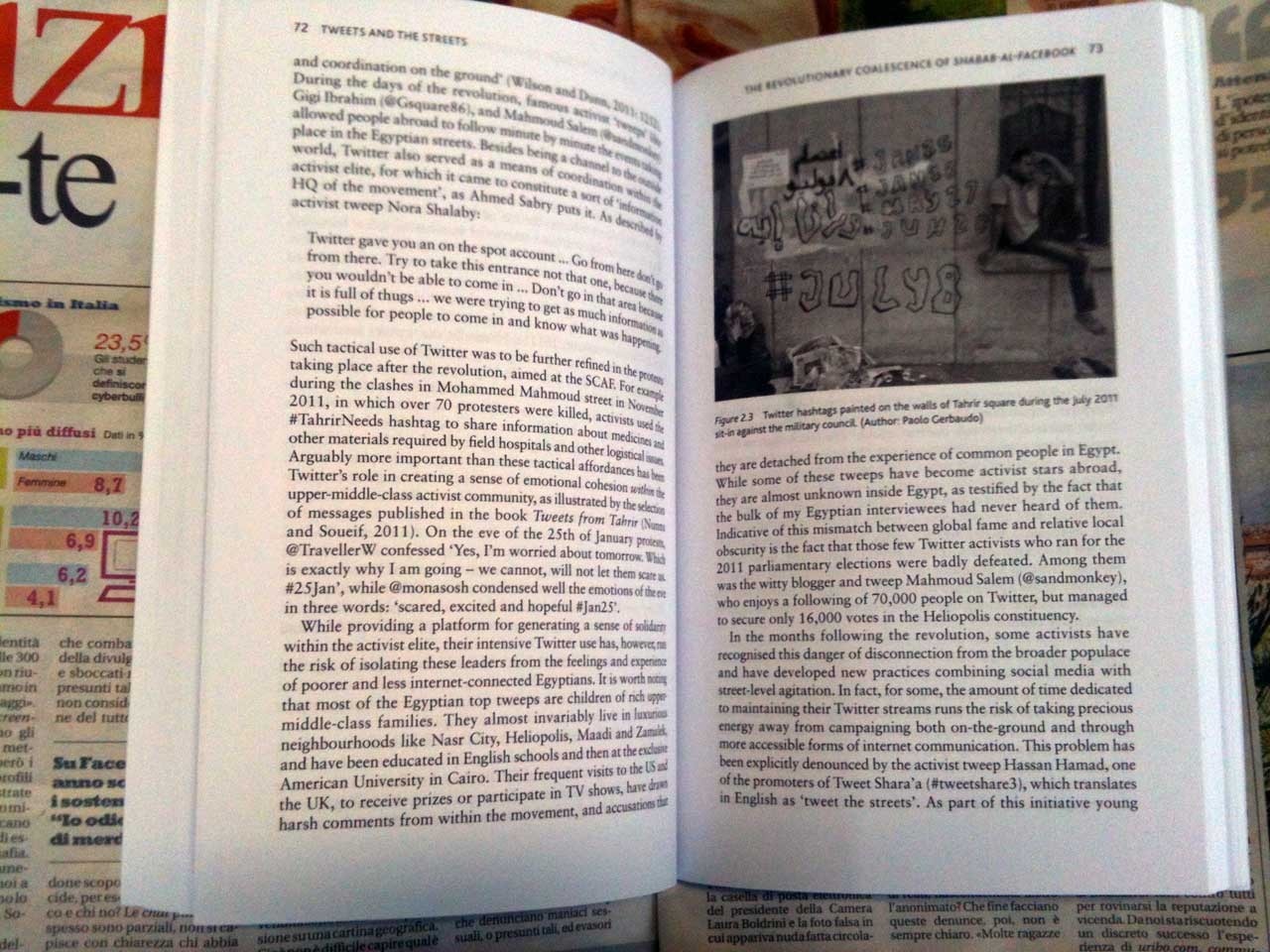

The sociologist shows how Facebook and Twitter helped young Egyptians (just as it did young Spaniards and Americans) to build a strong emotional connection to the idea of struggle