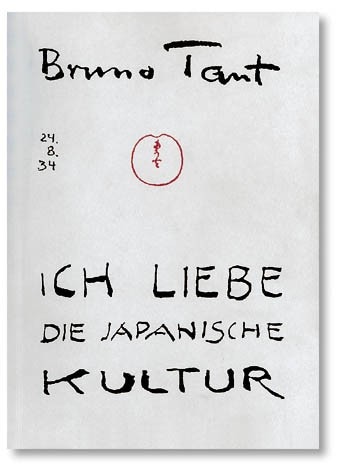

Ich liebe die japanische Kultur. Kleine Schriften über Japan, Bruno Taut , A cura di Manfred Speidel, Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 2005 (pp. 240, s.i.p.)

Bruno Taut is a continuing revelation. His trip to Japan, which he described in three books, is well known. Numerous publications – essays, criticisms and reprints – have in recent years tried to bring the legacy of the architect and urban planner persecuted in his homeland back to Germany, but much remains to be done given the considerable amount of as yet unpublished material. This collection of writings edited by Manfred Speidel, a scholar whose name is inseparable from the words Taut-Japan, is a reminder of this.

The book’s first and last essays outline the chronology of Taut’s Japanese exile (March 1933-October 1938). These sandwich 20 varied written pieces – eight of which appear for the first time: articles, letters, projects and a diary page make up a cleverly balanced anthology divided into nine themed sections, almost betraying a didactic intent. Let us, instead, try to read the book from beginning to end and imagine that Taut himself, the contemporary cultural mediator, is leading us through “his” Japan. The first pieces are brimming with passion on every page and recount his European and Modernist eye first coming into contact with the Japanese culture. We see an alternation of houses, traditions and concepts (“Nihon”, “Shinto”), rather like impressions gained on a flight through towns and cities, and narrated with an attentive eye and words that are always clear and penetrating. Faced with the “universal wonders” of Nara, Ise and, most of all, the Katsura Imperial villa (see also the review “La princesse est modeste”, Domus 886), at the time unknown in Europe, the discerning eye becomes quiet and contemplative.

A few pages later the flight is rudely interrupted as Taut’s mood changes. Hence the title of the book, which cites a surge of emotion immortalised in the book on the Shorinzan Temple, is not a declaration of unconditional love for the host country. The disenchantment emerges after a more careful and critical examination of everyday life and in particular residential architecture. The traditional home, initially presented as the most logical consequence of the Japanese lifestyle, is actually anything but ideal or suited to withstanding the climate, the country’s true scourge. The “new” architecture that Taut saw around him was nothing more than an imported pastiche, an imitation of Western models and therefore equally unsuited to its purpose. There was a lack of foundations for the birth of a new Japanese architecture that could develop in harmony with the surrounding environment instead of denaturalising it or being denaturalised. The figure of the contemporary architect was not given its due credit: Prince Kobori Enshu, the legendary architect of Katsura, was not allowed a symbolic progeny and to contemporary eyes he was as far removed as the Tenno from his subjects. Instead, it is indeed tradition, and Katsura, that produced the only source of renewal for Japanese architecture. Architecture is good (“gut”) if bound to the national character and able to rise to a universal standard of quality to become “Weltarchitektur”.

Only apparently, therefore, are we at the extreme opposite of the International Style written in large letters on the other side of the Pacific Ocean from 1932 onwards. Taut’s thought is actually an appendix to the idea of an “International” style, the annulment of the exchange between the international and the nation (note: here, Taut intentionally ignores the Japanese nation’s deviated exaltation that resulted in the 1933 invasion of Manchuria), the former leading to the latter. This theory sounds clear and positive in the book’s foreword, but the words Taut uses to explain it trace out a far more convoluted path. His Weltanschauung is not conciliatory. From his point of view, architecture is good because it responds to the needs of the place in which it is built and for which it was intended. This suggests an underlying need with a capital N, almost the inescapable and ancestral force known to the Ancient Greeks: you cannot say that the discovery of the national character is an enlightening and cathartic solution. It represents a new utopia, an absence of place in the literal sense. Taut, an esteemed architect in Japan, recognised the solution to the problem, but was hardly able to build any of the 14 projects he had in the pipeline.

The writing remains clear and informed, but as you read on it becomes resigned to something inescapable. His “Kulturkritik”, finely portrayed here in the final sections of the book, detaches itself from standard practices and customs such as the kimono and its social function; crafts are credited with more cultural autonomy and Taut focused greatly on them in those three years. It is as if the architect and urban planner - prisoner to a fame heightened in Japan and abroad “only” by his role as the chronicler of a new world - had remained trapped there but was also shut out. The now disenchanted gaze of the observer seems to probe the obsession of an architect who was a victim of his own pragmatism.

This is the underlying concept that appears between the lines of the book and was seen briefly in Speidel’s comment in the 2001 monograph (Milan, Electa) when he said that “an architect cannot feel at home where he does not build”. How far removed from Iain Boyd White’s “visionary” Taut! We must note that the texts included in the volume do not cover the whole wealth of reflections that form Taut’s Japan. That said, this anthology has a fine and simple graphic design and is enriched by an eloquent foreword by the editor (a reworking of an essay also presented in the 2001 monograph), essential notes and a measured number of illustrations – photographs, drawings and pictures from the repertoires of Taut, Speidel and of other origin uniformly presented in reassuring black and white. It is a happy medium between a compendium for scholars and an appetiser for a wider audience. Only this would explain the raison d’être of this infallible recipe, produced with tried and tested ingredients and seasoned with new material. The Prussian master teaches, “Hohe Qualität gehört der ganzen Welt” – “the best quality belongs to the whole world”, and this book proves it.

Donatella Cacciola. Art historian