Francesca Esposito: Technically speaking, how do you stop time?

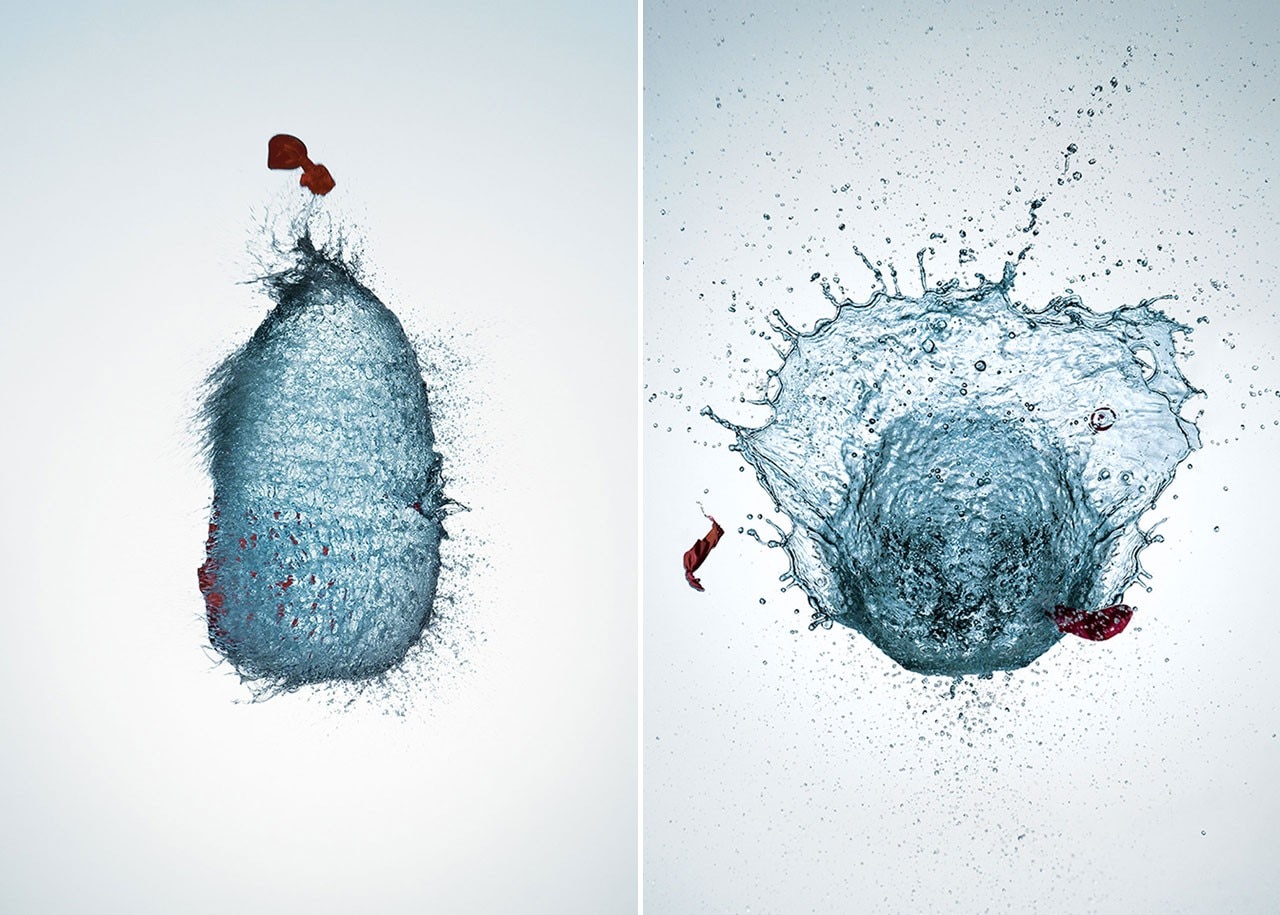

Luigi Ziliani: Shooting at a ten-thousandth of a second is all down to the right equipment. Broncolor flashes can make the flash last at speed and its maximum force for a ten-thousandth of a second. It is fairly advanced technology as a flash usually lasts a five-hundredth of a second but that would be too slow as a drop traces a trajectory in a five hundredth of a second. A ten-thousandth manages to freeze the phenomenon. The other difficulty is doing it at exactly the right moment.

FE: Easy to say but how can you be certain of determining the right moment?

LZ: Antonio Usuelli, an engineer friend of mine, and I built a fairly simple infrared sensor. When the infrared ray is interrupted, it triggers a circuit and sends the input to the flash generator, which decides when and at what force to release the flash. This gave us the mathematical certainty that the phenomenon would be captured in that precise moment. We attached a digital electronic keyboard to this sensor so that we could tell it to wait a ten-thousandth of a second. Then we improved on it with trial and error, and some secrets, naturally.

This homemade apparatus enabled me to snap the exploding Campari bottle pictures that, thanks to my agents, were chosen by Campari for their advertising campaign.

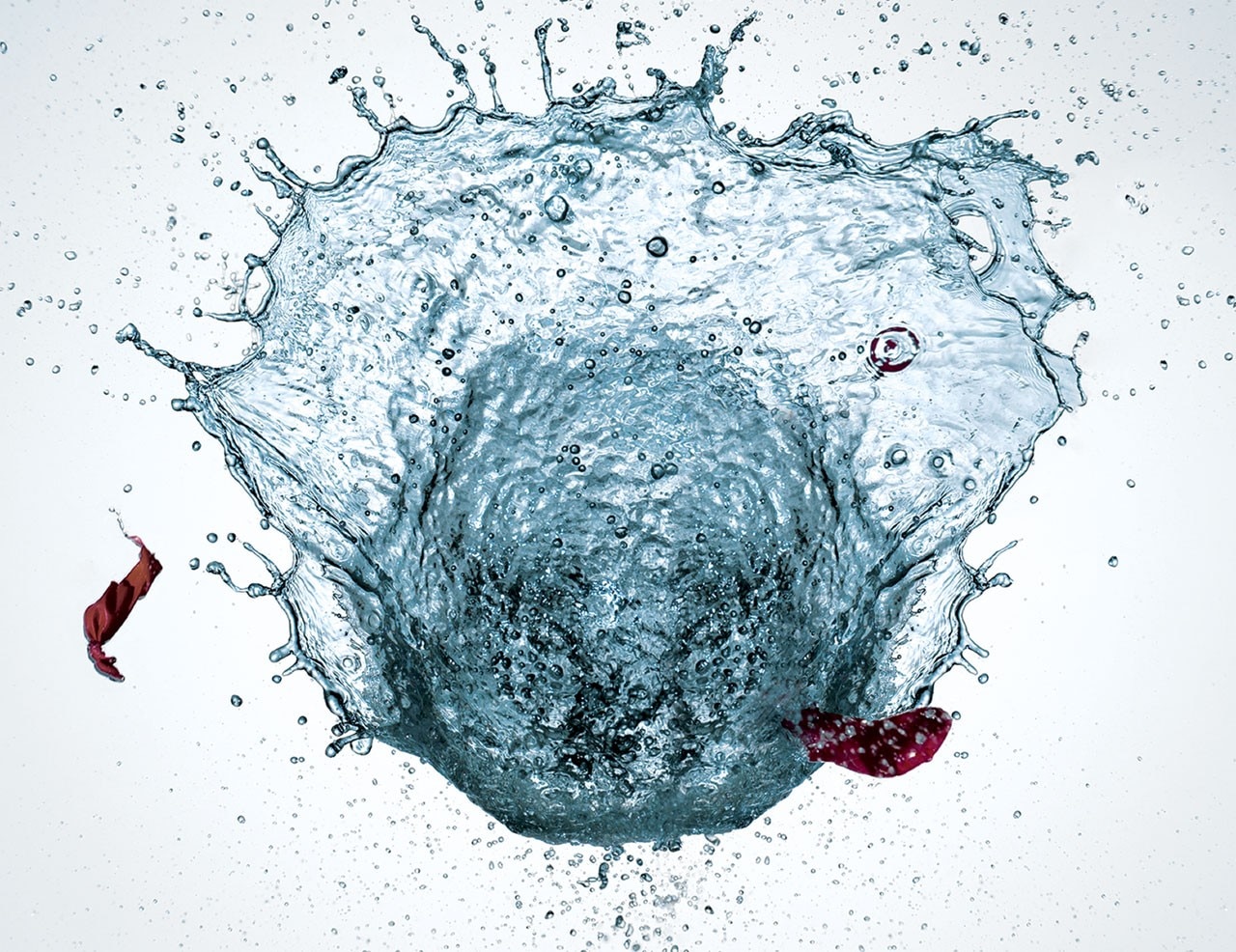

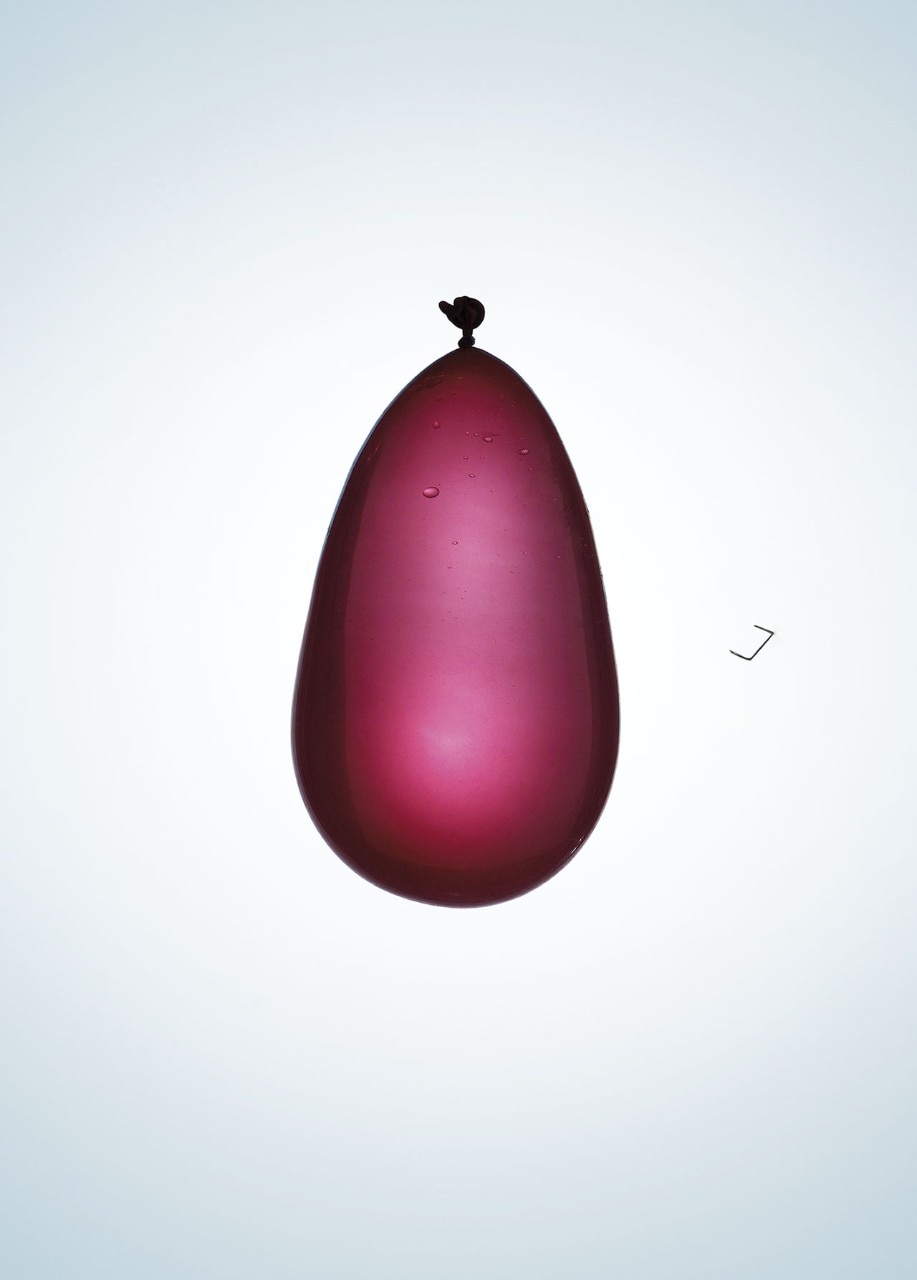

FE: You used an inductive method, started with an experiment. How did you immortalise the water shapes?

LZ: Initially, I chose the water balloons because I did not yet have the technology to set off the flashes at the exact moment. Besides, they were obvious, inexpensive and spectacular. Then, I started conducting experiments with bulbs, milk and liquids with different consistencies. Those were mainly unrefined experiments, photographically not very appealing but scientifically interesting – what happens when a drop of ink falls into milk? I tried, made a mess and split stuff. Then, I decided to do something more demanding, conveying the scientific effect but also making space for the aesthetic factor.

FE: Who and what inspired you?

LZ: I have always been fascinated by the infinitely small and the infinitely large, from galaxies and supernovae down to microscopic insects. There was a book in my home with photographs by Edgerton, more an engineer than a photographer, who invented the stroboscope and constructed flashes that could capture the anatomy in movement. I tried to emulate his method in my projects and that is where it all began.

FE: Who are your photography masters?

LZ: Everything has already been done; nothing is totally original, new or never seen before. We all have own style but are inspired by other photographers and masters. Edgerton was my prime master but also Guido Mocafico and Norimichi Inoguchi for still life; and great reporters such as Capa, Bresson and Salgado. There are also the big fashion names such as Steven Meisel and Peter Lindbergh but let’s say that, when I started out as an assistant to some fashion and advertising photographers, I was lucky enough to work with people who allowed me to grow, both professionally and as a human being. They gave me the space I needed to try and test things, experiment and ask questions.

FE: What must a photograph do?

LZ: Today’s photography, on a par with directing and painting, must be a narrator. Photographers must feel the need to express themselves and communicate because they have something they want to say. When you have nothing to convey – an emotion, a concept or a story – you do not produce good photographs. When you underestimate the technique, the Greek τέχνη of your craft, it shows in the results. You have to be very familiar with a number of elements, from lighting to the frame. You have to study and learn. The photographer Martin Schoeller, for instance, takes beautiful portraits but not simply because the subjects are interesting; it is also because he reveals what is hidden in the person’s gaze and their wrinkles. It is all a question of light and long, vertical reflections and, in such cases, Schoeller is good with the technique and neon lights at bringing out the portrait. If a photographer does not have this prerogative, then the result is simply a void. Sometimes, you must have the intellectual honesty to acknowledge there is nothing to understand and, most importantly, have the courage to say so.

FE: To end, is there a moment when the horse does not touch the ground?

LZ: Yes. For an instant, it seems to be flying.