So much more than simply the place where we prepare and conserve food, the kitchen is a highly symbolic coming together of what we are, what we appear to be and what we would like to be.

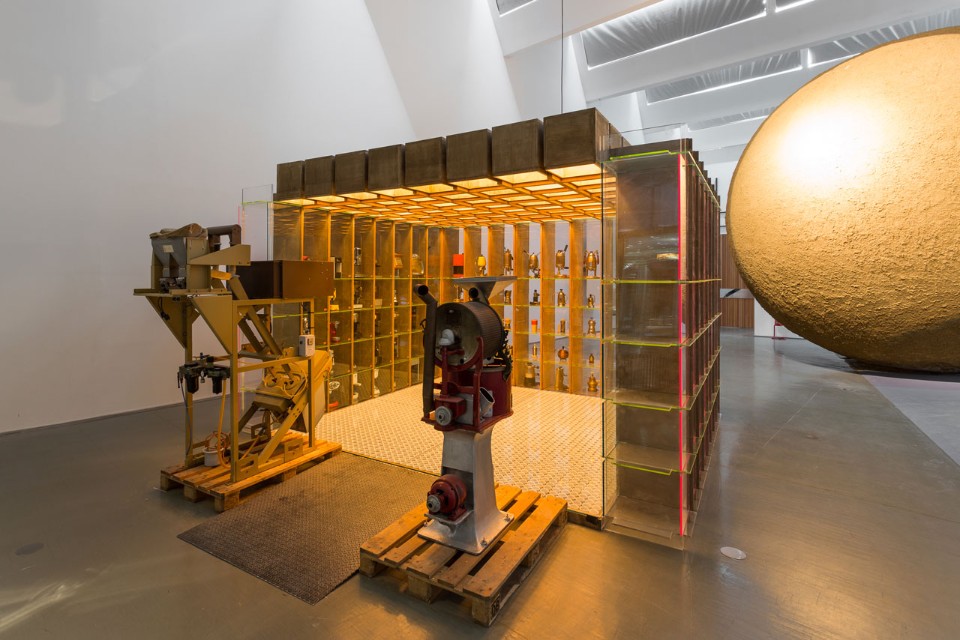

To illustrate this complexity at the 8th Triennale Design Museum, its curator and director Germano Celant and Silvana Annicchiarico opted for an angle that, perhaps more than all others, exemplifies the transformation from the artisanal kitchen to the industrialised one: the universe of electric appliances. Adopting the excellent metaphor of the Invaders, borrowed from The Bodysnatchers – a Jack Finney novel and a 1956 Don Siegel film – Celant has turned this type-story into an epic on the evolution of manufacturing. Electric appliances are far more than mute servants performing an action and become extensions of our bodies that boost our skills, demolishing the barrier between the natural and the artificial.

until 1 November 2015

Arts & Foods – Rituali dal 1851

until 21 February 2016

TDM 8: Cucine & Ultracorpi

Triennale di Milano