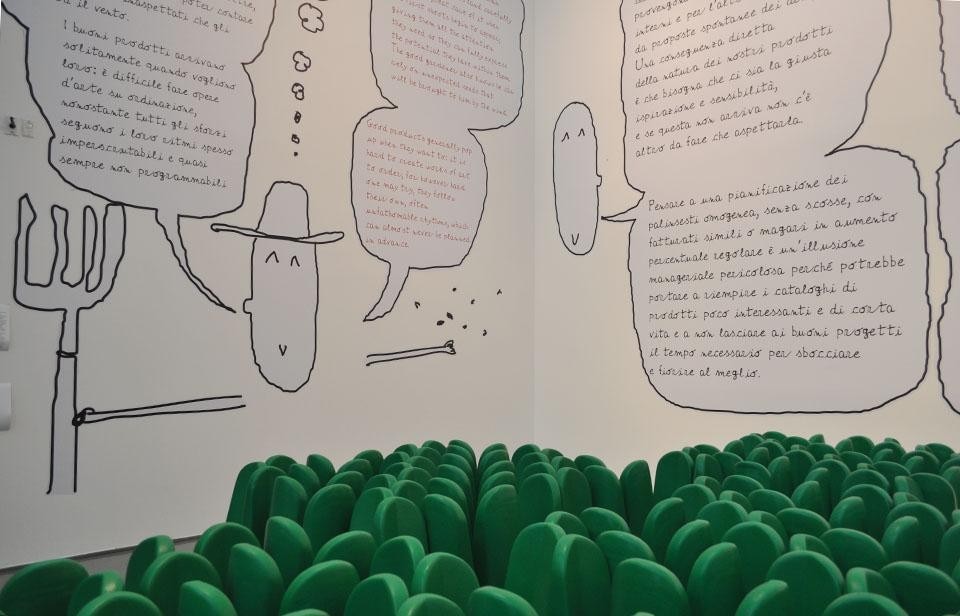

Marking the fiftieth anniversary of the Furniture Fair, the fourth edition of the museum makes for a colourful and crowded presentation before the eyes of the visitors, with dense texts that fill the walls and around 250 items with furniture set along the floor and lamps hanging from the ceiling along with tall yellow panels depicting key businessmen from the post-war period up to the present. The division into twelve categories suggests an unconventional take on the story of Italian design: from design intended as art and poetry (which satisfies more than just material needs) to borderline practice (between what is possible and what is not—and therefore a flop); from the rule-breaking component (a historic constant in Italian design) to the metaphor of the good gardener ("sensitive, attentive and patient").

Can you explain what the dream factories are exactly?

I see them as the last link, in terms of time, in a long chain that goes back to the British Arts and Crafts movement dating back to the mid 1800s, with William Morris and John Ruskin. Other links in the chain have been the Deutsche Werkbund, the Wiener Werkstätte, the Bauhaus in the 1920s…At the moment, the latest link is represented by these producers of Italian design that I sought to explore. What they have in common is the fact of being of movements, happenings, aimed at the market but with an extraordinary component of industrial culture tout court cultural and in some cases, even spiritual. Today we are much closer to a kind of industrial research laboratory. We are aware that our primary role is not so much to produce lights and coffee-makers. It is rather that of artistic mediators: on the one hand of the best expressions of international design and on the other the so-called market, the needs of the public, or as I prefer to say, the dreams of the public.

When I say dream factories I mean the companies that address more than anything the dreams and imagination of the public. It is not that [we businessmen] identify specific dreams and then say to designers "all of you work on this". It is just the opposite: we offer the imagination, like the garden outside, at the entrance to the museum. It is an area of free exploration. Where maybe Giulio Iacchetti chooses one flower and another designer chooses another; and this corresponds to areas of sensibility or interest or at times nightmares. It doesn't all happen in this deterministic way. That's the job of marketing.

Could we say that this is the role of the designer? To offer input and make one dream?

The designer today absolutely works by addressing the public imagination. In this sense he is no different from a filmmaker or a gallery owner. The complication lies in the fact that you need to make objects that at times also have to function. I haven't sorted out this story yet. But an object can function up to a certain point. It is not necessary that it is all perfect. I explain it well with a formula, a mathematical model that I developed a number of years ago and that has the aim of showing what the public will think of the things we make. The model consists of four parameters: function, price, communication and imagination.

I haven't thought about it, I chose it because it is one of the things I have always been drawn to but perhaps it is true that in moments like this, in the paradoxical attitude of the world of stories I don't want to say we find refuge but at least we can find answers.

So what was your aim in deciding to take a story-like approach?

It was what felt closest to my heart. It was the way I wanted to sell a theoretical idea that I have been developing over the course of many years but that had behind it a component of ingenuousness, of naivety. Before Guixé I worked on this project with another designer but then I realised that I needed a different designer, someone more childlike. Also to have a continuous back and forth, as is always the case in the best Italian design.

I hope that it can be an exhibition to experience on different levels. Starting with the lowest one dedicated to children, which Martí has made. But also at a more superficial level, at one more for design professionals and on up to a more theoretical level with the longer texts.

What is the common thread that runs through the choice of objects?

There are about 250 objects on show. Of these, a core of a hundred is irreplaceable. Another 150 meanwhile could also be different because the panorama is so rich. Each of them serves to illustrate one of the twelve chapters.

What criteria were used in the choice of businessmen?

It was done by placing the bar very high and choosing no more than about fifty. They are a genuine directory of the factories of Italian design from the last seventy years. I have to say that apart from two or three which are the result of a compromise, on all the other names I would stake my life. Don't ask me which they are, anyway you can see: they are the ones with the biggest bags of euros.