Can an interior evoke at least one moment of literature if the request is for a homage to Franz Kafka, where his archives are kept on the ground- and basement floors of a 19th-century building? And can this be accomplished without being slavishly metaphorical or theatrically falling into the trap of literal reconstruction?

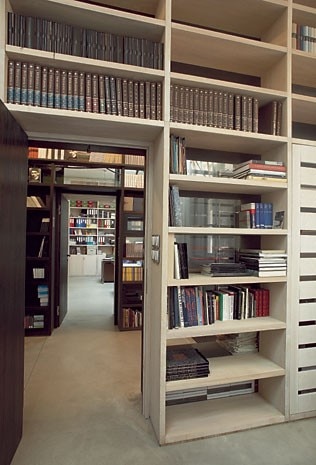

Steven Holl’s two projects entrust the metonymic process to a few pieces of fixed furniture elements, thanks to which a single part can spatially recreate an entirety, pars pro toto. In both, the focus is on constructing the space around one fundamental or primary object: books in Prague and a supercomputer in New York.

Somewhere on his sketches, Holl wrote: “Franz Kafka: ambiguity in black and white.” He transfers this sovereign feeling of ambiguity to partitions – where we hear sounds through a piece of furniture without seeing their source, where we catch a glimpse of a space now, but cannot recognise it a few minutes later, where we can see through some parts, but not all. The rectangular room is cadenced by bookcases/partitions that are given the role of tricky transformation. A stage device, a simple sliding and rotational movement around a pin, is all it takes. By this mechanism, the books forcefully enter the space and design it transversally every time a two-sided bookcase (closed or opened; white or black) pivots around its hinge, in an orthogonal position relative to the frame of the vaults.

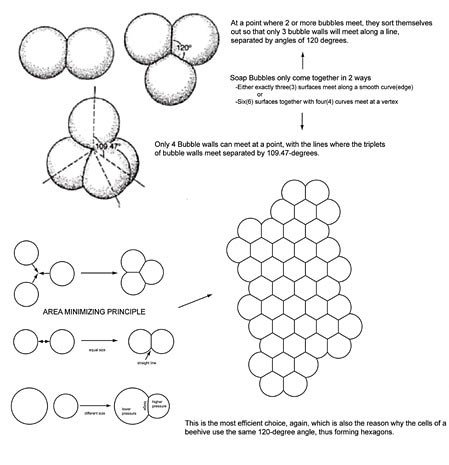

Something Jewish fi lters through in the tones of grey, black and white, just like the disappearing bookcase (typical of a secret room in a castle) indirectly refers to Kafka. But a more decisive move was needed to brand the project and exorcise the sense of “night” that shrouded the pre-existing surroundings: Holl opened a skylight by cutting through the vaulted ceiling in a desecrating (or simply modern) way, linking the chthonic world of papers with a patch of sky. In New York, Holl borrowed the chains of proteins and other biological macromolecules studied by D. E. Shaw Research to explore a different kind of geometry and its related intriguing secrets. Two types of spatial “intrusion” occupy the 32nd-floor lobby, adjacent to the elevator: a glass “bubble” built around the supercomputer, conferring sacredness, and a not entirely monumental staircase in the middle of the space, suggesting the presence of a second level. Both elements are sufficiently mysterious to allow only a partial, intuitive perception of their identities.

The staircase is visible, but not overly so (like when you arrive at the entrance of the Maison de Verre and you can tell, in a non-explicit way, through perforated steel screens, that the stairway behind might lead to the house). The area is enclosed by 24 glass panels whose jutting slant commands respect for whatever is probably contained there. Then we have the stairwell, whose ceiling opening does not at all correspond with the shape of its stairs, creating a dynamic effect in an otherwise quite stagnant area. Nor does the line of the faceted glass on the floor coincide with its line on the ceiling, injecting a shifting parallax into this technological urn that stands inside an otherwise quite standard lobby. The geometric procedure of discrepancy between plans (stairwell versus staircase; the meeting point between glass and fl oor versus the same glass meeting the ceiling) generates a kind of expansion tank. The result is movement, transformation. Screens and panels add to the transfiguration of the space. A lace texture à la Shirin Neshat was laser-cut into the stairs’ sheet-steel steps and parapet. Smooth panelling encloses the space, incorporating a plinth of LEDs that refl ect in the dark, glossy floor, giving an atmospheric sensation of “being elsewhere”.

Ceiling height in a New York skyscraper is what it is, but here, we are somewhere else.