A number of incursions into the theatre have been made by contemporary artists: over recent years for example, the Teatro San Carlo in Naples has commissioned Valerio Adami to design the set for Il Vascello Fantasma (2003), Anselm Kiefer for Elektra (2004) and Giulio Paoli for La Valchiria (2005). In 2006, South African artist William Kentridge will be designing for Il Flauto Magico.

It is rather more rare however, for architects to try their hand into this field. Their creative interventions are only due to elective affinities with the theatre and the music, such as for example the relationship that united Renzo Piano to composer Luigi Nono, for whom in 1984 he designed the sets for the opera Prometeo.

Jean Nouvel and Zaha Hadid, meanwhile, have ventured into the world of modern dance with the design of a number of sets for Belgian choreographer Frédéric Flamand. Treading the boards arouses fear in even the most relaxed of performers; on stage one is completely naked, with no filters. Set designers are asked meanwhile to construct a space, to attempt to imagine how people move around within it. The final effect, that the public will see from the stalls and the dancers experience first hand, is born out of this interaction.

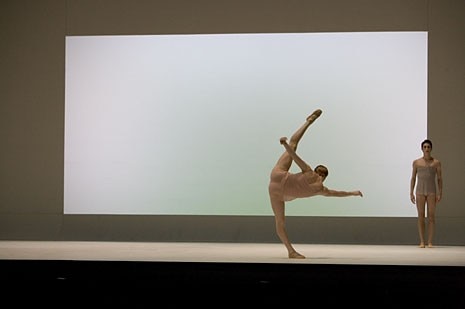

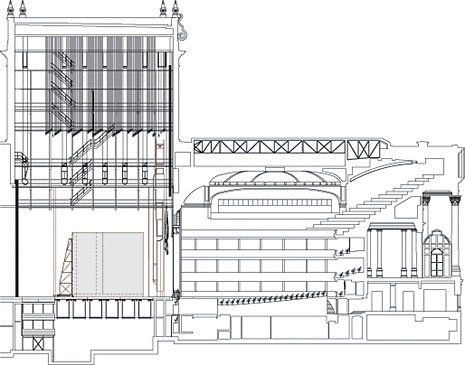

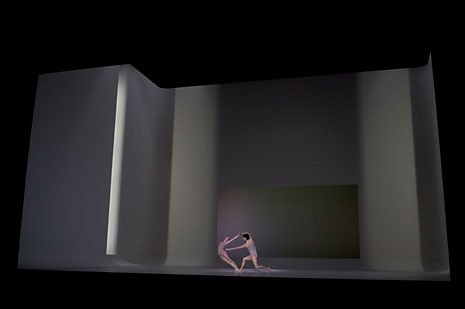

In this sense, the project that John Pawson has recently completed for the Royal Opera House in London – the sets for the modern ballet Chroma that opened in November 2006 – is proof of an uncommon sensitivity in the treatment of space: “All architecture concerns itself with the way people will use and move through space, but these dynamic issues are obviously heightened on a dance stage. Part of the specific challenge lay in the way that, unusually for an architect, work of this nature splits how space will be physically experienced from how it will be seen”.

Pawson was working for the first time in theatre, an environment with no natural light and he addressed it with a twofold strategy: the presence of a void and the design of light. The void that Pawson speaks of is derived from what he defines as a “mental image”: it is the mysterious presence that flutters within the two large openings cut out of the inside of the apse of the Cistercian monastery he designed in Bohemia. Here the void is present, but also made mysterious through a succession of lights of varying intensity, the same technique used in the design of the sets for Chroma.

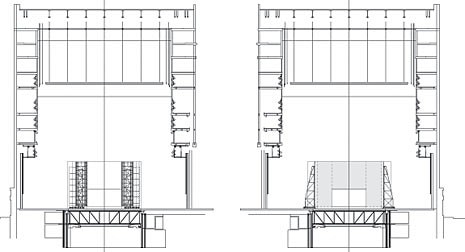

Pawson has raised up a fixed structure with an opening at the centre of the backdrop, along with the movement of the dancers it is only light that changes the state of things; through its modulation the screen behind appears to come forwards or move away. It is also a way of enclosing the void within a kind of frame, whose dimensions relate to those of the dancers.

http://www.johnpawson.com