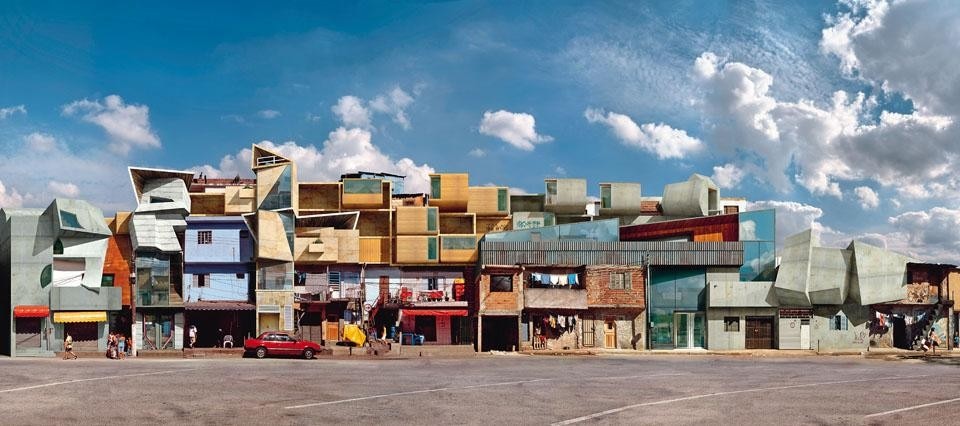

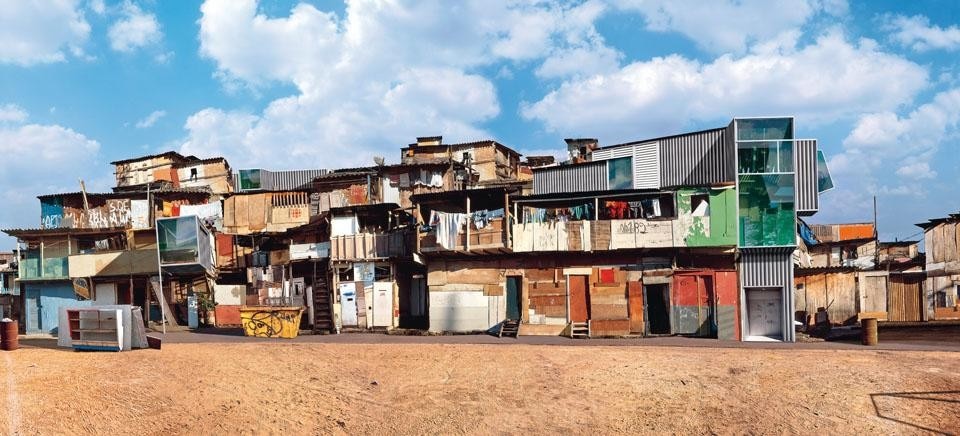

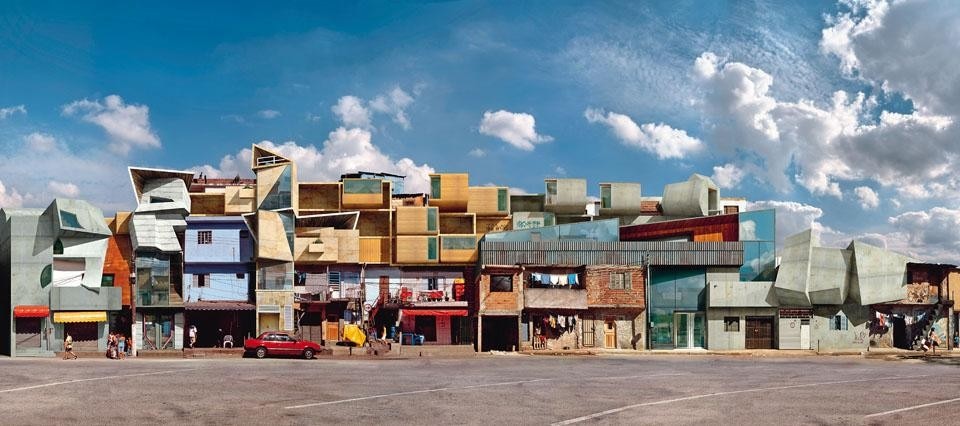

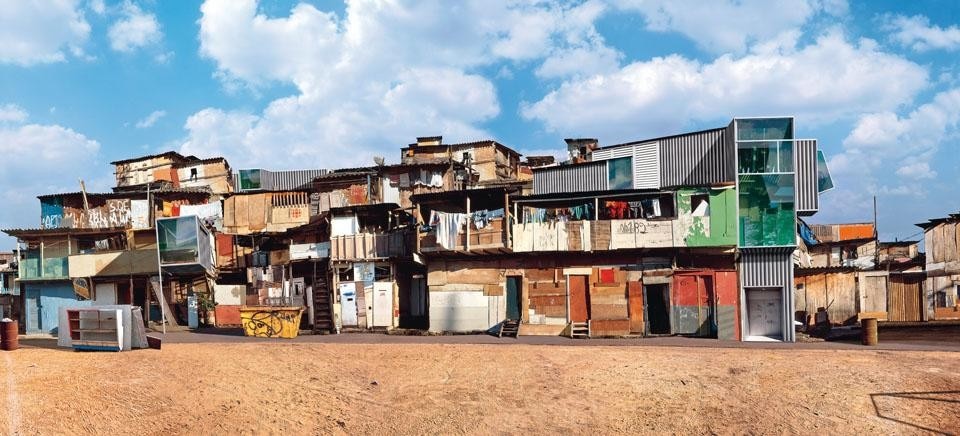

In between a metal wall and a container, a shack or a rotting wood partition, González inserts architectural modules of a recognisably contemporary style, in glass and metal, geometrical and essential.

In between a metal wall and a container, a shack or a rotting wood partition, González inserts architectural modules of a recognisably contemporary style, in glass and metal, geometrical and essential.