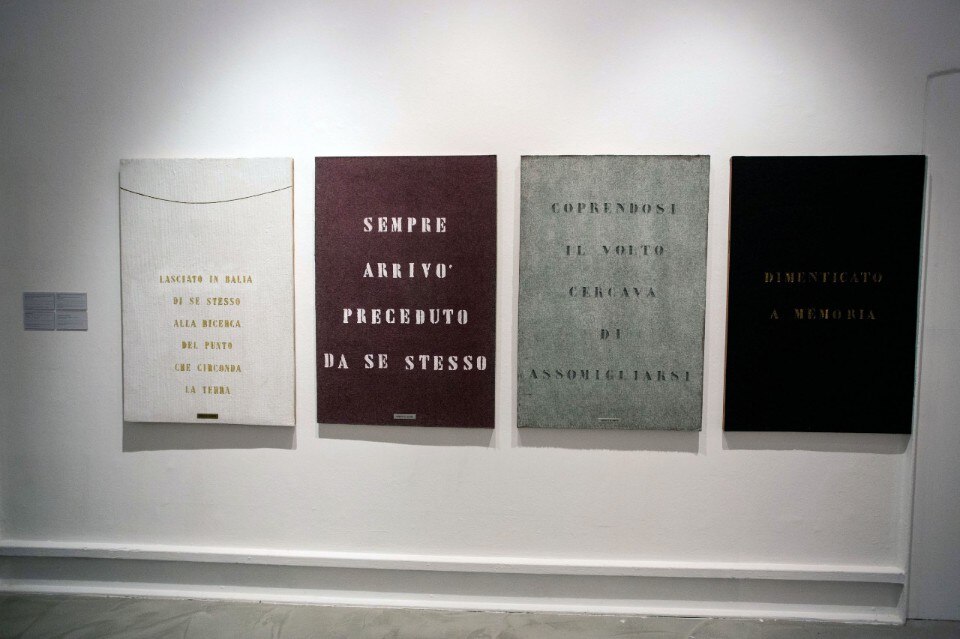

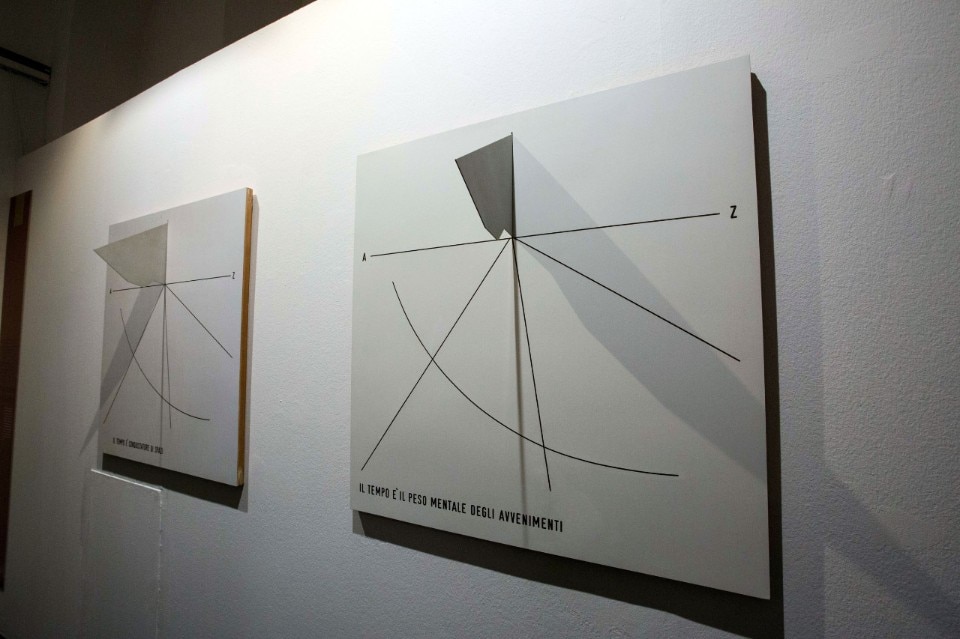

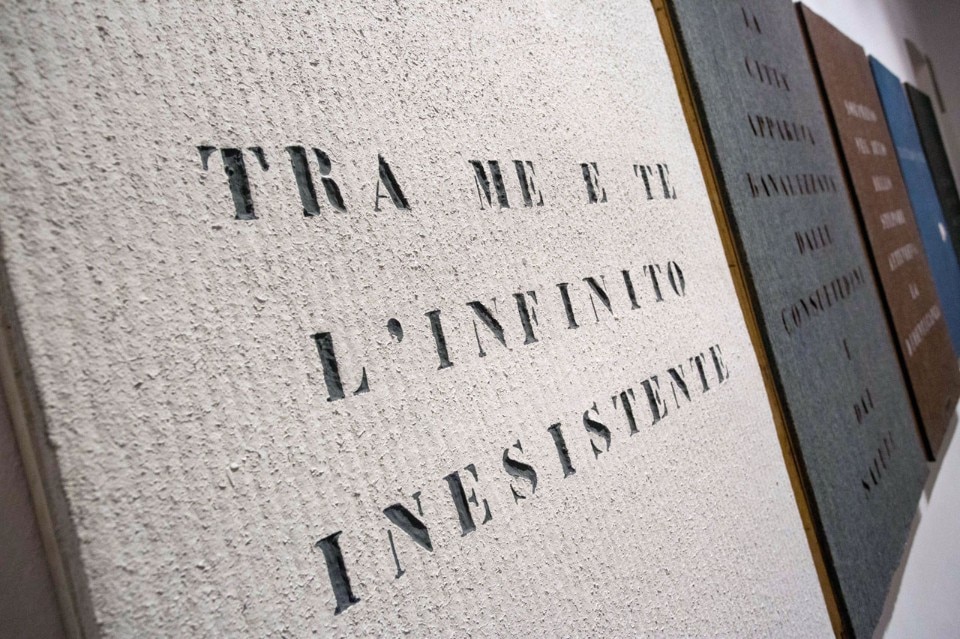

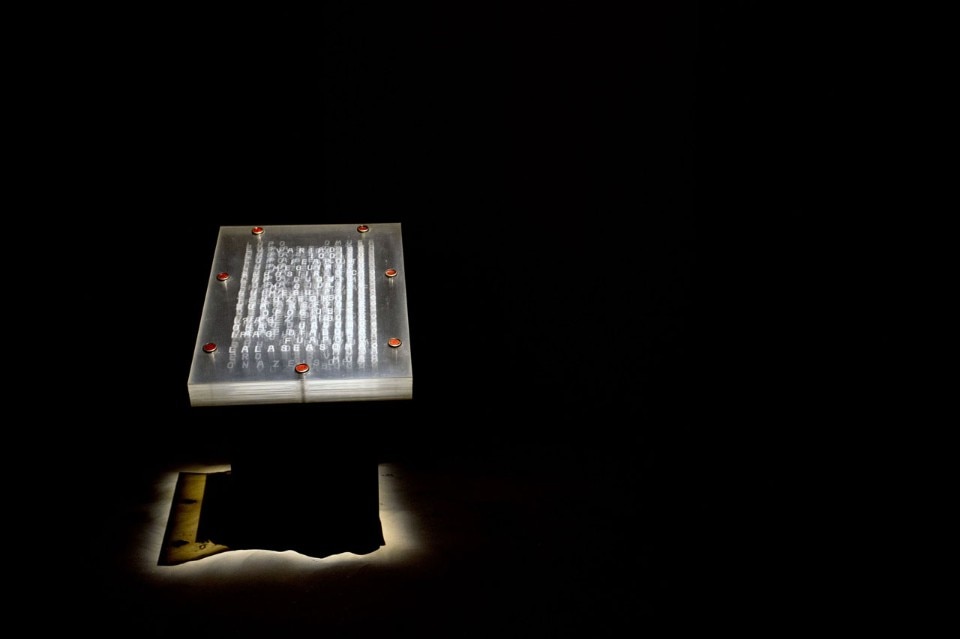

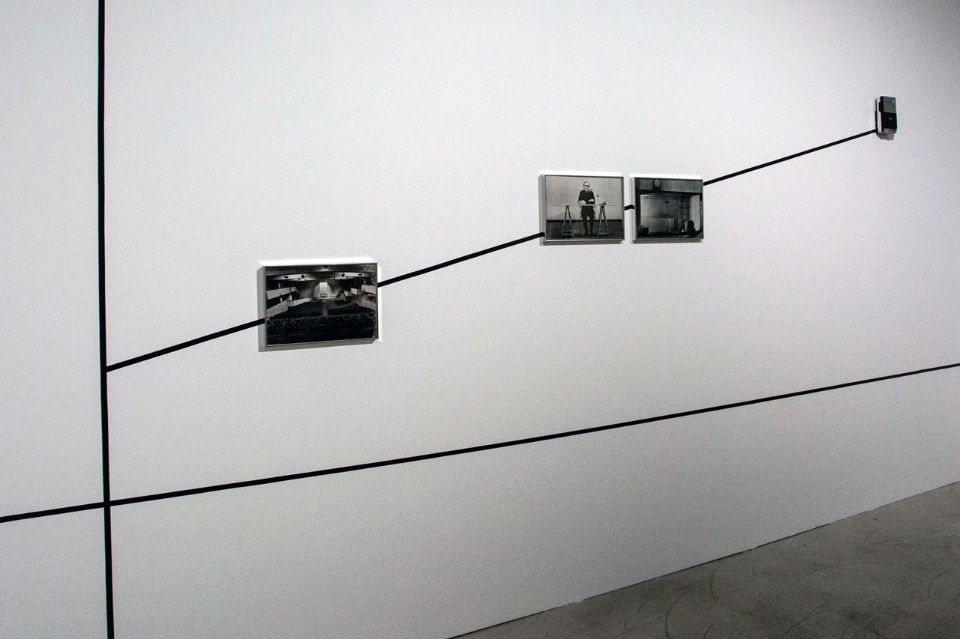

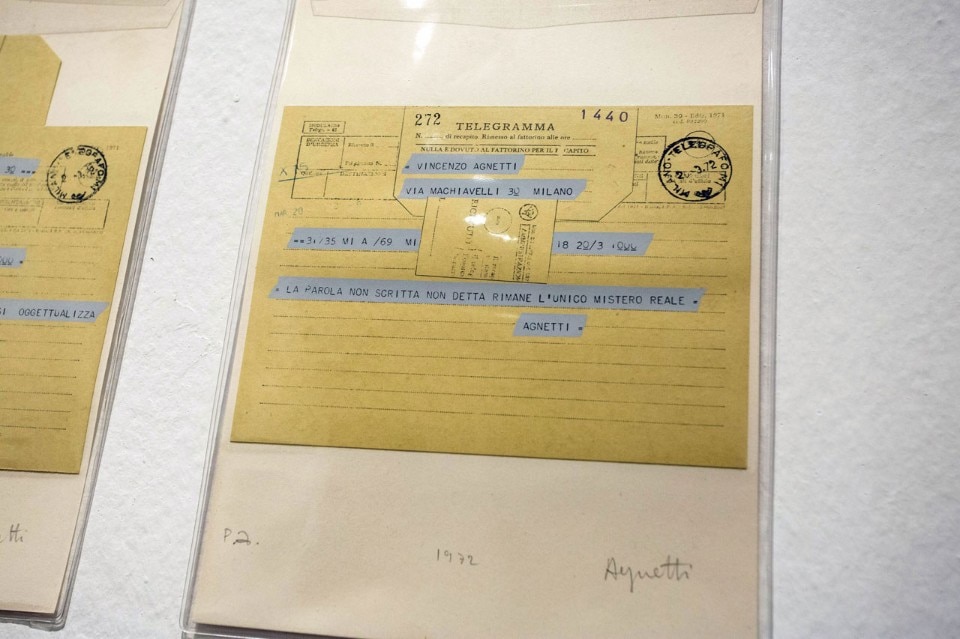

The exhibition itself has something chronometric about it (in the sense of precise, punctilious) and also something combative and rushed (the promotional poster features a photo from the 1979 series La lettera perduta, where the artist trips and falls with a great pile of letters in his arms). The title of the show, “A cent’anni da adesso” (“One hundred years from now”), was chosen for being a phrase he would often repeat, according to his daughter Germana. She is the president of Archivio Vincenzo Agnetti, which organised the anthology together with Marco Meneguzzo. The title aims to connote how time – cyclical, slow, tired – was the cornerstone on top of which the artist’s entire production was stacked. The examples are many, innumerable even, but one is the mute series of sundials, Tempus Mentis (1970-1971), encountered as soon as you enter. Their long shadows sound out not the hours, but thoughts. In their slow rotation, they caress phrases whose subject is time itself. Next to them hangs L’età media di A (1973), where a woman’s face looks like a tin can crushed by an automobile. Then there are the famous “telegrams” Quattordici proposizioni sul linguaggio portatile (also 1973) – “Fourteen propositions regarding portable language” – of which Agnetti is both sender and recipient. They appear to have been thrown around by the sluggish shade of a giant gnomon. The four large dark windows of Stagioni are on display, as they were in 1980 at the Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea in Milan, Agnetti’s last show. In some of his work, time is passé: we could call Obsoleto a novel-cum-manifesto written with Scheiwiller. One thousand copies of it were published in 1962 with a cover by Enrico Castellani. In other pieces, time is something yet to come, as he declares in one of his famous maxims that can be seen in his studio at Via Machiavelli 30 in Milan, handwritten with chalk on a black sheet of paper dated 1975. It says, L’artista coglie solo frutti acerbi (“The artist only picks unripe fruit”).

until 24 september 2017

Agnetti. A cent’anni da adesso

Palazzo Reale di Milano

Curator: Marco Meneguzzo