Despite or because of this, the Voice of Images exhibition, drawn from the François Pinault Foundation's video collection, conveys a specific and crucial message on using art to re-launch an experimental and intense reflection on moving images in conjunction with the 69th Venice Film Festival at the Venice Lido. Art offers us a space where we are not bombarded with video-jingles of various length and form. It is a niche — metaphorically speaking because the exhibition is spread over 2,000 square metres — where we can draw a sigh of relief. [1]

The exhibition is on display until 13 January 2013 and the curator, Caroline Bourgeois, traces an in-depth and far-reaching path that is distinguished by a wealth of different applications and examples, covering the entire — albeit brief — history of video art.

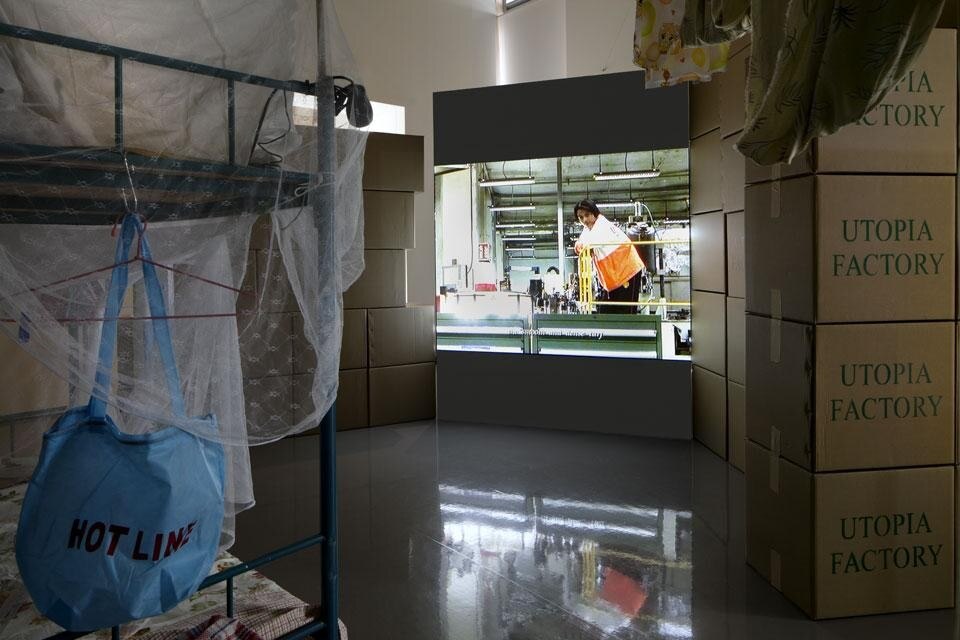

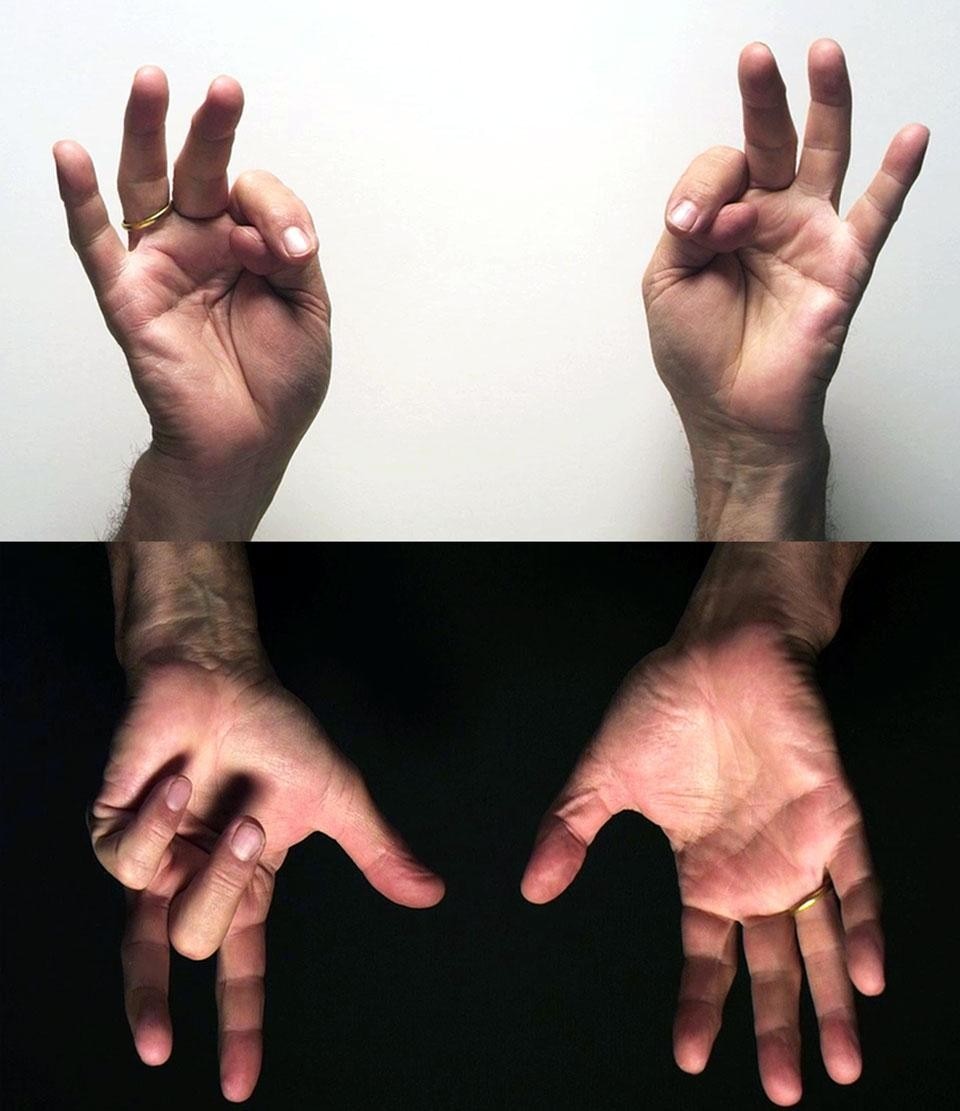

So, on the one hand, we have Bruce Nauman with his giant wall projection of For Beginners (all combinations of the thumb and fingers) (2010). A sort of sign alphabet created by two pairs of hands to instructions from a voice off-camera, it empties the artwork of all spontaneous and direct meaning to focus on the difficulty of making art and being an artist closed in your own studio. On the other hand, there is Johan Grimonprez 's hall installation Maybe the Sky is Really Green and We're Just Colorblind (2012), a YouTube-otheque that literally and critically assembles video clips taken from the mass media, the Internet and social networks, recreating the sense of fragmentation and zapping typical of contemporary information world.

Art a niche — metaphorically speaking because the exhibition is spread over 2,000 square metres — where we can draw a sigh of relief

There are some in which sound is totally absent and the installation is silent. Campo San Samuele 3231 (2012) by Zoe Leonard reconstructs a camera obscura in her room on the Grand Canal, with a small hole closed by a lens in the darkened window. The upside-down image of what is captured in outside Venice through the hole has an inner voice which envelopes those looking at it and prompts a fascination with the silent "view" that changes in two ways during the day — in content and in position.

1.The Palazzo Grassi exhibition shows the Foundation's major focus on this medium which, as the director Martin Bethenod writes, has never failed to appear in any Palazzo Grassi-Punta della Dogana exhibition since 2006. Equally, it falls within the renewed interest in video art within the city's cultural production, which started with the Video Medium Intermedium Biennale exhibition. There are also the Foundation's itinerant exhibitions, especially Passage du Temps curated by Caroline Bourgeois which, in 2007, was held in Lille, reiterating the French city's role as a point of reference, given the presence of Le Fresnoy, the video production centre and contemporary art school, and France as a country that is highly sensitive, more so than Italy, to everything that concerns moving images.

2. Programme for the next four months of the exhibition in the two mezzanine cinema-rooms:

September: documentary films on confinement

Temps mort (2009) by Mohamed Bourouissa and Nocturnes (1999) by Anri Sala.

October: narrative film works

Liu Lan (2003) by Yang Fudong and Faezeh (2008) by Shirin Neshat. November: videos on the theme of experience

BB (1998-2000) by Cameron Jamie and Comédie (1965) by Samuel Beckett and Marin Karmitz

December: works presenting the viewpoint of young artists

T'as de beaux vieux, tu sais... (2007) by Bertille Bak and Lake (2012) by Erin Shirreff

Voice of Images / La Voce delle Immagini

Palazzo Grassi

Campo San Samuele, 3231, Venice, Italy