From White Cube in central London to Gagosian in Chelsea and Arario Gallery in Seoul, dealers are experiencing the same frenzy that trustees suffered a decade before, competing paradoxically with museums’ programmes, fund raising and collection making. The art world steered towards greed in a very dangerous way, weakening the role of public institutions to provide content without fear of jeopardising attendance figures and media attention. While ambition in culture served to create legacies and options for a challenging future, today it only works if it can produce tabloid rumours and celebrity noise. Maybe the celebrity building that was so much at the centre of the beginning of this century was simply a vessel to free the frustration and the ambition of celebrity architects trapped in the quicksands of Seventies’ politics, followed by the frustration of museum directors and curators who from makers of content aspired to be producers of gossip and magazine covers. The challenge for museums, while going back to their origins with a growing public demand for ideas more than faces, is to avoid being considered as preposterous “Salottos” where celebrities from any field can incestuously mingle and evaluate how their cultural ambition can be transformed into substantial revenues and their presence substitute, momentarily, the aura of humble, unassuming works of art. The new New Museum is a signal in that direction, a new model for an old model of cultural institution. While communication among individuals has been revolutionised by the Web in a similar way to the Gutenberg revolution, physical spaces of conviviality from museums to theatres or clubs are stuck with old models.

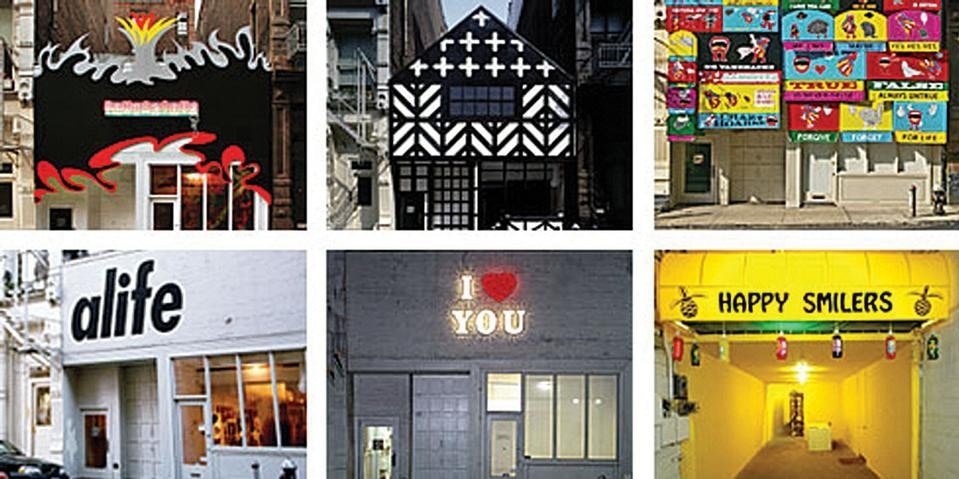

The need of the Fifties, Sixties and Seventies to be experimental or underground has been substituted by the obligation to be part of the establishment from the very beginning. Managing and economic structures from the MoMA to the Artist’s Space operate with the same method and follow a similar blueprint. No one seems to feel the need or the necessity to make a leap into a new operating model. Paradoxically, someone who was considered in the Eighties to be the ultimate art dealer, the dark side of the art world, Jeffrey Deitch, is maybe today the most interesting and hybrid player around, mixing in unlikely ways the market with underground experiments and an interdisciplinary programme, using different spaces as different platforms for different propositions, some market driven, some simply based on the challenge of discovery. Considered a very successful entrepreneur, Deitch’s strength has been to embrace failure as enthusiastically as success. Moving from Soho to Long Island City, Deitch Projects is mapping the city like nobody else. Of course Europe is a different case-study that cannot be compared with the New York art scene. But the European scene is also locked into old models. The many Kunsthauses, Kunsthalles, ICAs and so on often act with a confrontational Seventies’ attitude towards the mainstream and particularly the market. This Manichaean manifesto is very dated and is not bringing into the discussion new ways to present, discuss and explore the different art communities and their production.

If the New Museum was once the answer to the conservative limitations of the Whitney Museum, today no new cultural institution is really challenging the establishment. Or if they do, like in Europe, they do it by transforming an art institution into a social club, a branch of an unemployment office or an agency for theoretical studies. If in the Sixties and Seventies the rejection of the establishment was the spark that ignited innovative and daring operations, today everybody, from artists to young curators and upcoming dealers, is terrified of being rejected by the establishment. If rejection was once a career, today it is seen as pure and simple failure. Under these circumstances, it is hard to imagine new places or institutions appearing on the horizon. Economic prosperity or at least stability has produced an age of very stable offers. We are witnessing a generation of young, rampant, cowardly marketing strategists. If the Seventies were raped by a culture of slogans, the 21st century has been sedated by a culture of copyrighters. The result of all this is museums that look more like shipping or auction warehouses than spaces for the cultural players of the future.