(Don DeLillo, Players. Knopf (1977, p. 10))

On Tuesday September 11, 2001, two hijacked airliners crashed into two identical towers of 110 story each, at the World Trade Center in New York. What have we learned ten years later?

In Delirious New York, Rem Koolhaas argues that in early twentieth century, people sensed the promise of skyscrapers more intensely than the architects, who operate on Manhattan's land without altering the original layout of the city. Minoru Yamasaki, architect of the WTC, wrote that since the great economic crisis of 1929, until the start of the post-war, Manhattan's skyline had been fixed, interrupted by isolated actions amid a landscape made of mediocre or directly bad architecture that together, produced one of the world's most beautiful urban skylines.

WTC as World order

In July 1944 forty-three nations meet to negotiate the Bretton Woods agreement, a Brit-American plan, aimed at establishing an international economic order based on U.S. dollar supremacy, and seek to tackle the reconstruction of war-torn economies through expanding international trade. In 1945, developer David Scholz, proposed the concept of a "world trade center" to revive flagging maritime and port activities in New York, the authorization for the project came in 1946, same year that the donation of 8.5 millions of dollars was made, to buy the lot for the United Nations Headquarters,. In 1948 the U.S. Congress approved the Marshall Plan to support the economic reconstruction of Europe and, in 1949 NATO was constituted. The World Trade Center plan was part of a series of operations to position the U.S. as world power, within the framework of the Cold War post WW II.

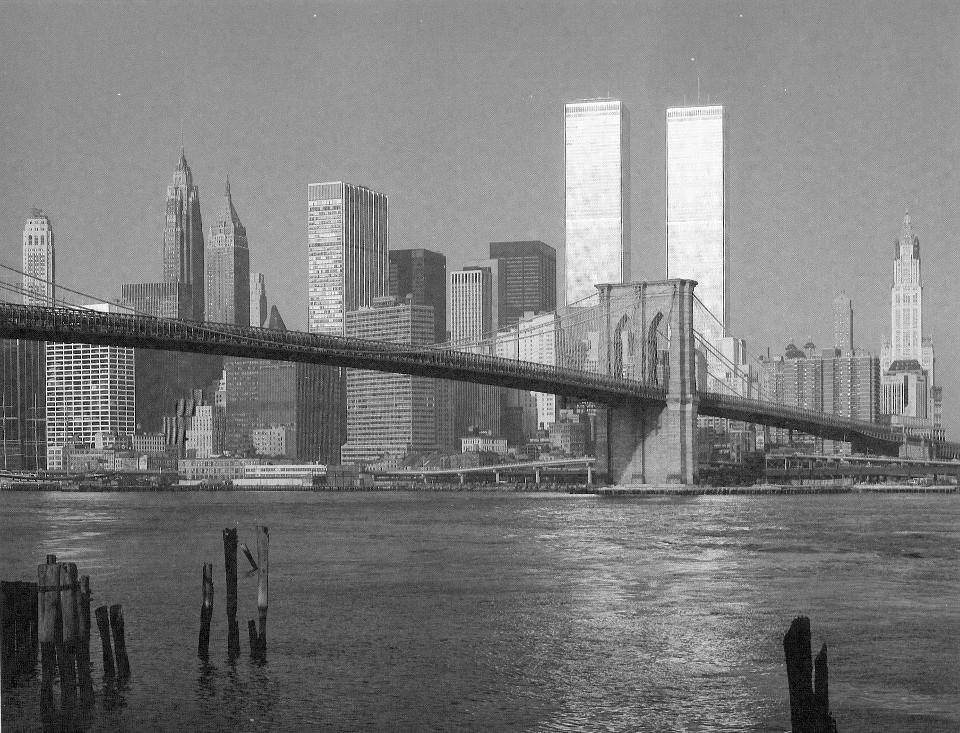

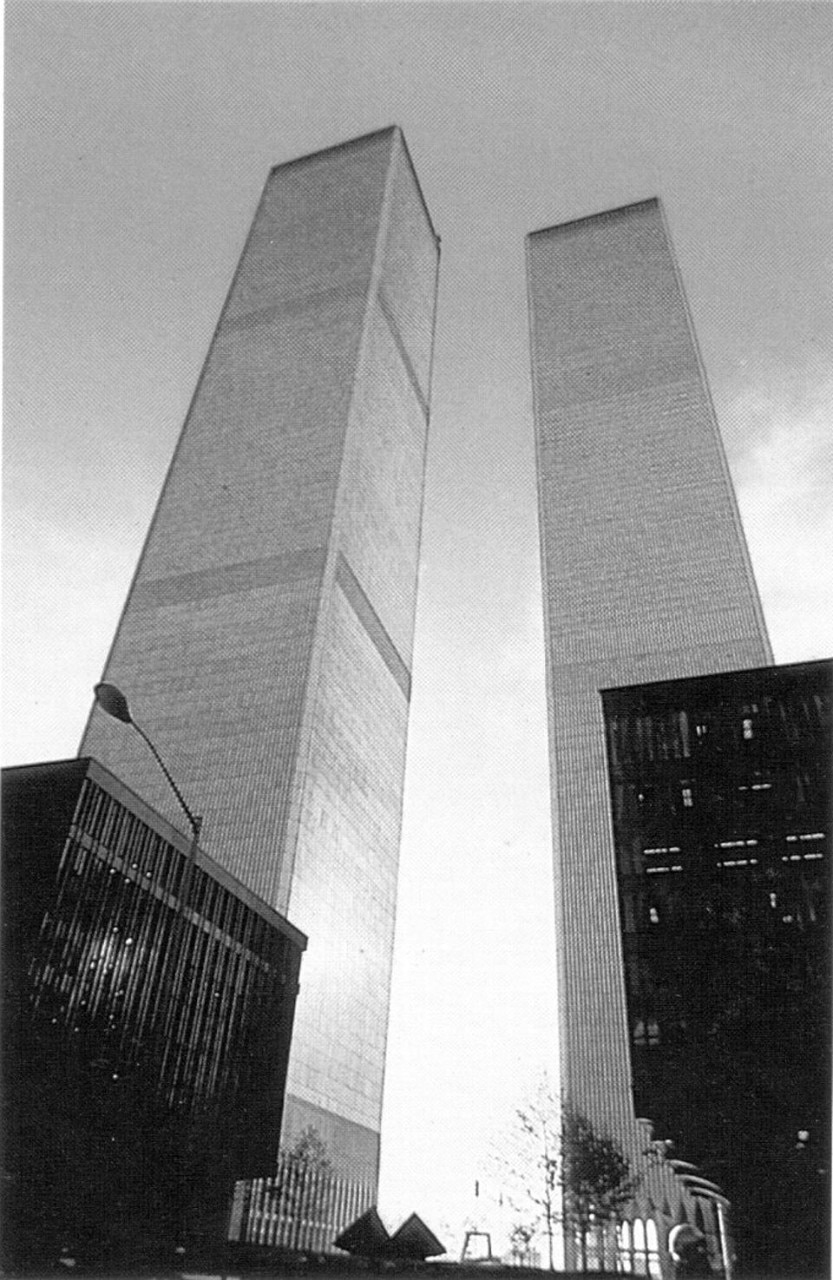

In 1955 the WTC became the trigger for a new urban planning in New York, including Lincoln Center and the renewal of Lower Manhattan. In 1960 a development plan for the World Trade Center was agreed and in 1961 its final location was decided: a damaged area on the end of the Hudson River where it would act as territorial recovery; the area was renamed as "Trans-Hudson Line". In 1962, the project was commissioned to the architect Minoru Yamasaki, a small studio from Detroit, the final proposal was presented in 1964—after 100 drafts—and the works began in 1966. Yamasaki's proposal synthesizes the vast and imposing requirements by the commission, in a single word: height. Yamasaki not only fulfilled the promise of skyscrapers, but addressed the problem of the territory, changing the fragmented layout of the area, building a super block that maximized the perimeter to a monumental public space that would enhance the impressive altitude of twin towers with its 110 floors, 431m tall, finally opening in 1973.

During its life, the WTC met fierce critics from citizens and architects, especially regarding the scale of its urban void, its minimalist aesthetic and, using a Koolhaas term, its "decongestion", a willingness to break New York's total saturation, however over the years it became the vertical magnitude of Manhattan, defining it's skyline, serving for the perfect take for any film set in New York as well for the most catastrophic fiction.

As with the Empire State's real estate financial balance, WTC's business results were initially a disaster, and only in 1980 it began to retrieve the investment, considering the project was an ambitious operation in public space and in the interests of the city. The success of the design lay not only in the radical difference in height to existing buildings, but in the two prisms being twins, which from a distance, appeared not as a circumstance but as a promise.

During WWII, Yamasaki avoided U.S. Japanese camps, protected his parents by moving to NYC, and became director of Goodwill Relocation Council of Japanese-American Organizations. After the war, and despite an early discriminatory environment he finally received his first important commission: the controversial housing project Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis, completed in 1955 and demolished less than 20 years later. Yamasaki built also the U.S. Military Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, one of the 20 largest buildings in the world and a symbol of militarism and the Vietnam War in the 1960s that remains operational today, after more than a dozen fires, one in 1973, that lasted more than two days.

That same year, Yamasaki and Associates completed the World Trade Center in NYC, which suffered it's first attack on February 26, 1993 by a Muslim fundamentalist group at an underground parking, near the north tower, leaving 6 dead and 1000 wounded, minor structural damage and 6 prisoners sentenced to 240 years in prison. Two years earlier, the Basque terrorist group ETA almost succeeded an attempt to blow one of his posthumous towers (completed in 1988), the Picasso Tower in Madrid, a formal remembrance of the twins and until then Spain's tallest skyscraper.

But the Twin Towers' fate would finally be sealed in 2001.

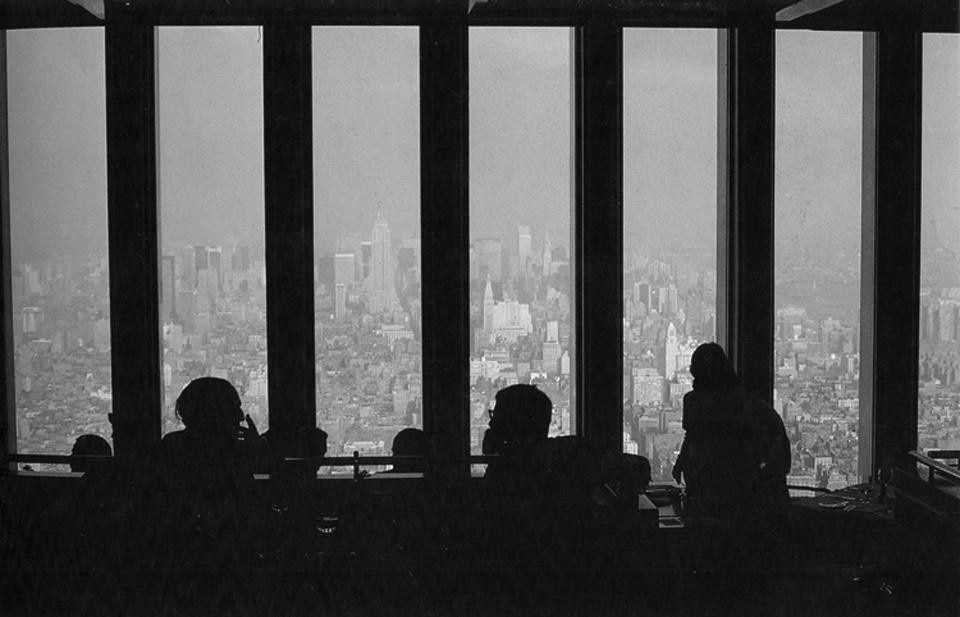

Yamasaki said that over the years the purpose of the WTC became "so basic and so obvious" that went unnoticed in the eyes of critics, it was simply the promotion of international trade at the port of New York to improve quality of life of the metropolis by the increase in revenues. It was a joint initiative by public and private agents, operating the same way to optimize the complex encounter between all the agents by concentrating functions.

But it became much more. Since its construction, the WTC was present at the opening curtain of TV shows and movies becoming an icon for the island. Until its filmic redundancy became its tragic fate that day, with the continuous replay of the American Airlines Flight 11 crashing into the south tower. Broadcast live to the world, the event constituted the biggest news special ever seen, almost overpowered all discourse on the "American way of life" produced on film since WWII. The silhouette of the WTC on New York's skyline represented success and development, a story built on the greatness and power of the will of the metropolis, where things happen, and therefore it is a basic 'American' tragedy, in which the fantasy of destruction is part of the process of construction with literature and pop culture having regular parallel narratives to the imminent tragedy; from The Manhattan Transfer to King Kong, displaying extraordinary disasters that only occurred in the city and being the destruction of it's icons a recurrent plot in science fiction movies, from alien invasions to multiple threats, stopped just in time by super-efficient security forces or fantastic superheroes.

The attacks temporarily suspended the release of Sam Raimi's "Spiderman" whose promotional poster showing an helicopter caught in the superhero's spider net, stretching between the two Towers, a scene that was eventually cut out of the movie: an Orwellian rewriting of history.

Minoru Yamasaki wrote earlier about his project that, as a gateway to New York, it would become "the physical expression of man's universal effort to achieve world peace". Against his pacifist intentions, (maybe derived from the Cold War context when it was commissioned) it's tragic end, ironically embodies the myth of the Tower of Babel, a symbol of destruction by cultural conflict and triggering a new form of xenophobia, similar to what the architect himself experienced in his professional start, which through the attacks has estranged the United States relation towards different cultures.

What was really attacked?

After Moscow's 1960 exhibition, famous for the so-called "Kitchen Debate" between Nixon and Khrushchev, where the United States was represented by a facsimile of a suburban house full of appliances, described by the Moscow press as "the sample of a department store", the understanding of the model of American democracy became more related to a simple freedom, to purchase consumer goods: An open choice from an infinite array of products—perfectly manifested in the built grid of Manhattan— making a statement through the endless skyline of corporate buildings, that Trade is our 'culture', legitimizing it as an 'ideology'.

Rebuilt—How does an adoption of symbols work?

As Sebald writes in A Natural History of Destruction, in respect of area bombing of the RAF over Hamburg, "under the shock of lived experience, the ability to remember is partially interrupted or operated as an arbitrary compensation" … its population had lost the mental capacity to remember, denial is the final objective of reconstruction; in the attacks, the territory was violated drastically like a natural disaster and the existing order needed to be restored.

While the fear gives way to a radical change in social behavior of a population, Architecture could become the positive mechanism of response to the attacks. Rebuilding would act as retaliation, to an undefined physical enemy, without a precise territory, and after some short political debate that lasted less than a year, proposals for rebuilding quickly appeared—even as a "a form of urban and architectural critic and academic experimentation ", and before too late an international competition for the newly-called "Ground Zero" is launched, resulting in a winning project by Jewish Museum architect Daniel Libeskind.

Cleaning and preparing the site consumed more victims and time, during which the main tower ceased to be called Freedom Tower and became a "public affair", renamed One World Trade Center, since as Port Authority executive director Chris Ward said in the New York Times: a building named "the Freedom Tower" meant "a visceral reminder of 9/11", so we decided to change the project into something that "real estate industry understands" to which the developer and leaseholder Larry Silverstein added "Fear is never a good selling proposition".

A decade after the events, we can ask whether this response from both, war and architecture was justifiable, or if it was hasty, and then, why so many prominent architects, supposed thinkers of our time, answered the call, without raising alternative responses to "bigger, stronger, taller", or if as the New York Times wrote born by "the emotional consequences of destruction of the World Trade Center, of hubristic folly", and especially the name "freedom tower" that according to the same media, corresponded to a vertical monument over a commercial office building which is expected to be profitable, posing the question: Who wants to work on the top floor of a target? And,What is the priority of ground zero?

How to evaluate the architecture that was caused by a violent military act that ended up finally just as a speculative "vacant lot" operation? Will the new building answer to the cultural and historical context that generated it?

How to evaluate the architecture that was caused by a violent military act that ended up finally just as a speculative "vacant lot" operation? Will the new building answer to the cultural and historical context that generated it?

Ten years later, the whole project is costing twice the original estimate, with WTC1 expected to be ready by 2012; with a public space that is a forced void transformed into a memorial due to the impossibility of repeating the founding-principle technical challenge of Yamasaki's original project; with incessant media coverage of reconstruction that has lost its sense of purpose; with thousands of legal insurance and healthcare cases lingering without a near or clear end.

New Yorkers had just become accustomed to its new skyline, but a tower resurfaces, and Yamasaki's dream is only an immeasurable Square. Perhaps the ultimate answer was given by Don De Lillo's 1977 novel Players, in the form of a set of questions:

On the 83rd floor of the north tower, Pammy managed to spend time thinking up a question to ask to Ethan Segal. If the elevators at the World Trade Center were places, as she thought they were, and if the halls were mere spaces, as she believed, then, what was the World Trade Center itself? A condition, an event, a physical event, a circumstance exists and given in advance, a presence, a state, a set of invariants? Ethan did not answer and she changed the subject.(DeLillo, Players, p. 14)

Minutes after, an American Airline Boeing 767 breaks through the windows of their office.

Pilar Pinchart