Kulapat Yantrasast: I was trained under Ando, who's a very decisive master. Many architects and artists of his generation share his mode of operation: speaking one design language, strong and clear. The poetry and clarity of people like Ando, Gehry or Richard Serra are admirable, but I feel that in this moment — in 2017, the way it’s going —we cannot speak just one language. We have to create new and different expressions all the time. For that reason, I welcome collaboration and I am pulled by curiosity, which runs through all of our projects, from most minimal to most maximal. If design is a language, I think we at wHY speak multiple tongues.

Katya Tylevich: Do most clients share your enthusiasm for multilingualism, or do they prefer the idea of a “master”?

Kulapat Yantrasast: A big part of whether or not we take on a new project is how unique and interesting the clients are. Sometimes unique, eccentric people are very difficult to work with. [Laughs.] But in general, people who love architecture are eccentric and unique. If you think about it, our clients always have the option to go out and buy a new condo. So, to bypass that easier option in favor of making something bespoke really reflects who you are. Our clients find an architect to create a kind of self-portrait of them.

Katya Tylevich: Not a self-portrait of the architect?

Kulapat Yantrasast: When an architect manipulates a project away from the client too much, the client might enter the space and find they can’t really live there at all.

Katya Tylevich: Reality meets expectation…

Kulapat Yantrasast: Yeah, that’s what life is. And with architecture, you never really know until it's done or lived in. The occasional client will say: “Oh, I didn't know it was going to be like this.” Best case scenario is that it’s better than they’d imagined.

Katya Tylevich: You work across an impressive range of scales. Are you able to maintain the intimacy of working on residential projects when working with major institutions?

Kulapat Yantrasast: I think my case is unique, in that I actually started with big projects right away, and the smaller ones only happened after some time. Because of my work with Ando and the reputation and references that came with it, my first project with wHY was the Grand Rapids Art Museum in Michigan, just two months into opening the studio. But those projects only underscored how important communication is in the realm of architecture. We’re lucky to be working across 20, 30 cities right now. That means we don’t have the luxury of relying on a go-to engineer or concrete person. Every time, these relationships start from scratch. And if you don't have the friendship, support and collaboration of everyone from the engineer to the client, you are totally helpless. I never see architecture as mine.

Katya Tylevich: Your offices are based in L.A. and New York — two jumping off points for different parts of the world. How does this play out in your practice?

Kulapat Yantrasast: I really do believe in the future of L.A. I believe that L.A. will be the capital of the rest of the world: it has strong ties to the Americas, it has strong ties to Asia, and those places alone compose three quarters of the world’s population. But you cannot know the new without understanding the old. So I connect back to Europe, via New York, for balance.

Katya Tylevich: What does the future of L.A. mean for the future of design?

Kulapat Yantrasast: Here’s what the future of design is not: one person, sitting in a dark room with a cape on, sketching. One person is not going to solve the world’s problems. That was the model of Frank Lloyd Wright or Le Corbusier. The future is the fundamental magic of collaboration with many different people. At the end of the day, architecture is about serving others: your, community, city, country, world. Unless you’re glorifying an oligarch or a tyrant, you need to glorify the multiplicity of everyone.

Katya Tylevich: I can’t help but read political allegory into that comment.

Kulapat Yantrasast: I believe that a healthy ecosystem is made up of different kinds of plants. If you plant 400,000 ash trees, one disease will bring them all down. So maybe the fights and disagreements we’re experiencing now are actually signs of a strong ecosystem battling unhealthy short-term decisions for a healthier long-term. I believe that, eventually, we’ll get to the right place. We're riding the last thread of fear. favore di una lunga portata più sana. Credo che, in seguito, troveremo il punto giusto. Stiamo cavalcando l’ultima ondata di paura.

Katya Tylevich: Is your process shaped by that belief?

Kulapat Yantrasast: I often return to this idea by philosopher Krishnamurti: When asked by a medical student what advice he has for him to be a good doctor, Krishnamurti says that to be a good doctor, you have to be a good person first. Now more than ever, I believe that you cannot be a good architect — or anything else — if you are incomplete as a human being — with regard to sympathy, culture, and a desire to understand others. If you don't strive for the fundamental qualities of a good human being, then you're not doing your job, whatever it is.

Katya Tylevich: So good architecture is necessarily empathetic?

Kulapat Yantrasast: Look, you cannot be a good cook if you hate human beings! You’re feeding people! Aside from sex, what more intimate relationship is there? People put your work inside their bodies, they’re trusting you not to poison them. It’s the same with architecture: People trust you, they put themselves in your work. If you use toxic materials, if the space feels terrible for whatever reason, that will dictate how a person lives, how they face others, how they look at life. Everything. Architecture has that kind of power.

Katya Tylevich: How do your philosophies manifest themselves in physical reality? How are they reflected in Beverly House (Santa Monica, CA), for instance?

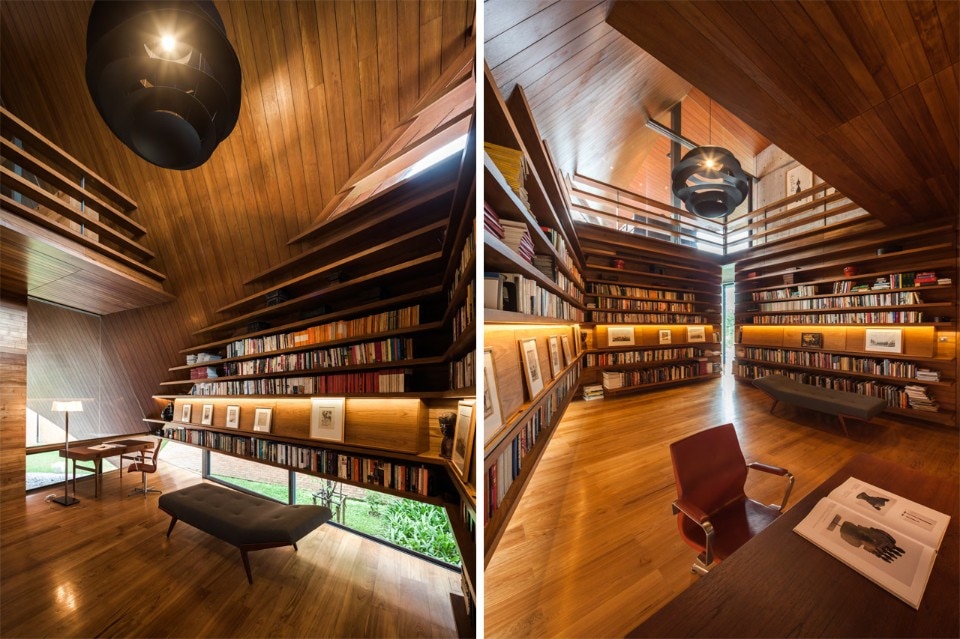

Kulapat Yantrasast: So, this is an example of really trying to understand a client’s unique approach to life. The project is a low-budget renovation, it isn’t a big project for the office, but it was an opportunity to work with a fascinating person. The client is as close to earth as a lizard: he likes to lay in the sun with his shirt off, be one with the elements; he’s a surfer and a vintage car mechanic. When he talks about what’s important to him in life, I make an effort to really listen. More and more, I got the sense that he would be happiest living in a tree. So, the result is a house whose exterior looks like rough bark, but inside, you see the contrast of a refined wood: the inside of a tree. The stairs, which double as a bookcase, connect his work and life together in the center of the home.

Katya Tylevich: You completed the Chiang Mai House (Thailand) around the same time — it suggests a completely different kind of life.

Kulapat Yantrasast: Yes, completely different, reflecting the clients’ union of British and Thai cultures, as well as their love for art. These clients were interested in the idea of how one can live in a modern environment while maintaining a sensitivity for traditional culture and values, and addressing the wet, humid climate. A glass box wouldn’t do. In this case, I really wanted to reflect their rich intellectual life together, as well as their location. Chiang Mai is well-known for its bamboo umbrellas and there’s an idea that the umbrellas are a kind of portable shelter. I was thinking about that when I came across a sweet photograph of a kid using a big palm leaf as an umbrella, to protect himself from the rain. It reminded me of doing the same thing when I was a kid. The idea for the house grew from that: Chiang Mai House gives the appearance of a leaf growing from the earth and covering its inhabitants, giving them shelter, with a very modern plan below it: square rooms. The leaf actually becomes one wall of the house, creating more of a connection. Most people never see their own roof, but I like the idea of connecting with your shelter.

Katya Tylevich: And what is the story behind Amoroso House (Venice, CA), which unfolded at the same time?

Kulapat Yantrasast: The Venice clients are a realtor and a famous restaurant owner, who share my interest in the idea of a geode: rough on the outside, with a contrasting refinement and clarity of thought within. They wanted one big space that still maintains a Venice quality: the scale of a cottage, a closeness to their walkable neighborhood. When you live in Venice, you want to live an open life. So, the first floor is a pavilion lifted on a concrete plinth, with glass in the front and back of the shared rooms; the living areas, surrounded by nature, feel like the interior of a courtyard. The bedrooms are connected by a corridor, but each one is designed to be unique, like a Venice bungalow. Each room has its own charm. I like the idea that if you cut into a plan, you pull out a different piece of cake with each slice.

Katya Tylevich: A healthy, diverse ecosystem, even in one house.

Kulapat Yantrasast: Well, I’m not interested in carrying a toolbox if it only contains five hammers.