Salvator-John Liotta: It will be hard to forget the time I spent in Tohoku. I think it's the closest thing to the end of the world I have ever seen.

That Norberg Schultz expression, the genius loci—which to be honest I have never really enthused about—came to mind while I was there. I was surrounded by a sea of debris, fetid air and a stench of things dead and rotting, and fragmented and shattered memories kept popping up all over the place. Who knows why but while I was there I thought of the genius loci. The affected areas no longer have the loci or even the genius. It is as if spirit and energy were no more. It is a spent place and it will take a long time to recharge it.

We have three projects underway at the Kuma Laboratory of Tokyo University. The first is the Gareki Museum or the museum of rubble, a symbolic place that will be built using the debris produced by the destruction of the earthquake and tsunami.

The second project is the 1000$ House. Houses are the real problem because the living conditions provided by temporary containers are humiliating. They work for a while but then people need dignity of life. So we thought up some very low-cost solutions, using recycled material, industrial waste etc. as construction material, all retrieved at zero cost and which would enable us to achieve the extremely difficult aim of building a house with 1000 dollars.

The third project is based on collaboration between the Italians for Tohoku association and the Kuma Laboratory. We are working on public-service architecture for Rikuzentakada. It used to be a beautiful town but is now devastated and has been adopted by the Italian community in Japan. We hope it works out as it would be a hugely positive signal.

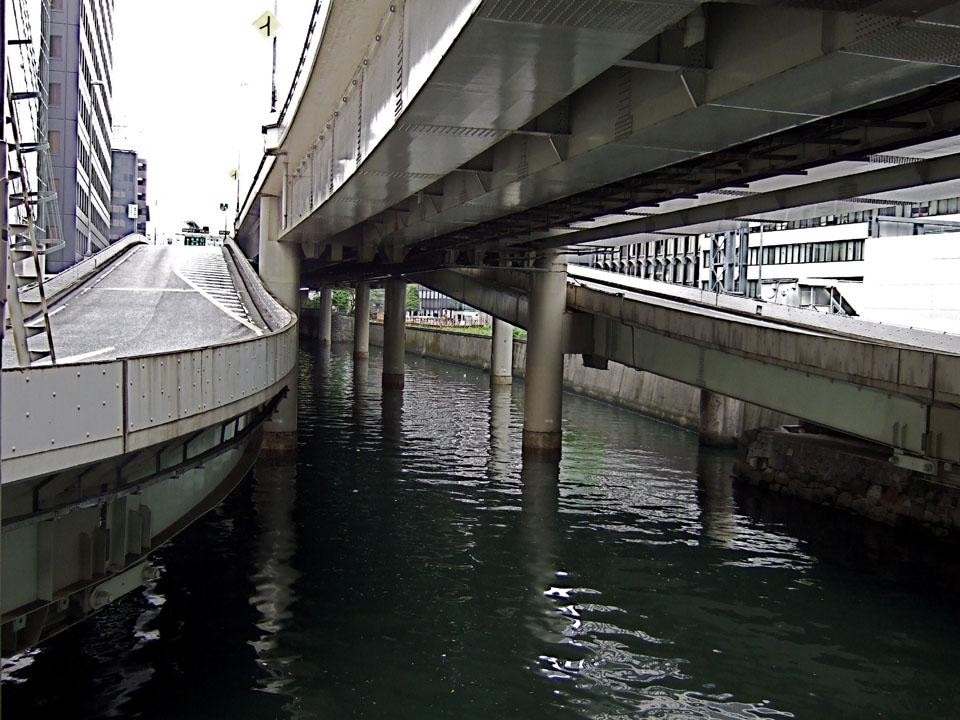

There are two books, Tales of Edo Prosperity and New Tales of Tokyo Prosperity , bestsellers of the early 1800s and 1900s respectively, that show us the differences between a pre-modern Edo and a Tokyo that had opened up to the world and was starting to participate in the modernity of the Western states. Edo was the name of Tokyo before the Emperor moved there in 1868. At that time, the palace of the Shogun (the highest military rank which had previously governed in the Emperor's place) was in the centre of Edo. A convolution of water canals spread out from it, intersecting here and there with other canals, to define the urban layout of the city. This water network provided Edo with its transport system. What is more, trading, encounters and performances always took place near the bridges.

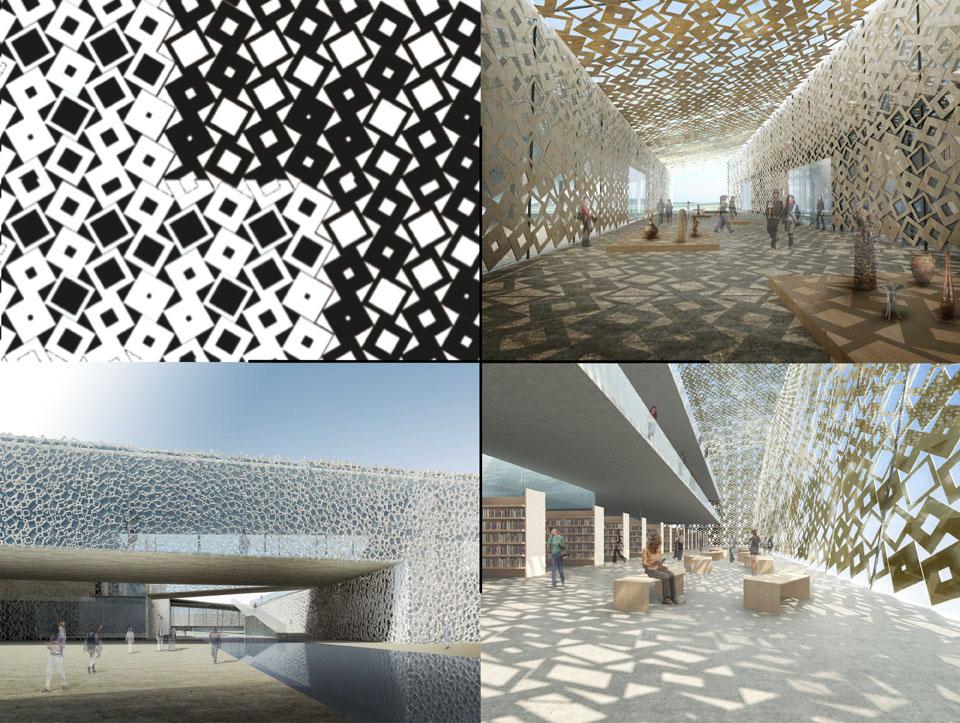

After being abolished from modern architecture because considered pointless ornament and not organic to the design process, patterns are today being seen by digital architecture as dynamei or potential generators of form.

People certainly want change.

In his latest books, Kuma writes about how the world will be 'Japanised' because traditional Japanese architecture is a treasure trove of examples of intermediary and transitory spaces that can generate architectural solutions compatible with the current demand for a greater awareness of nature. I, too, am working on this to some degree.

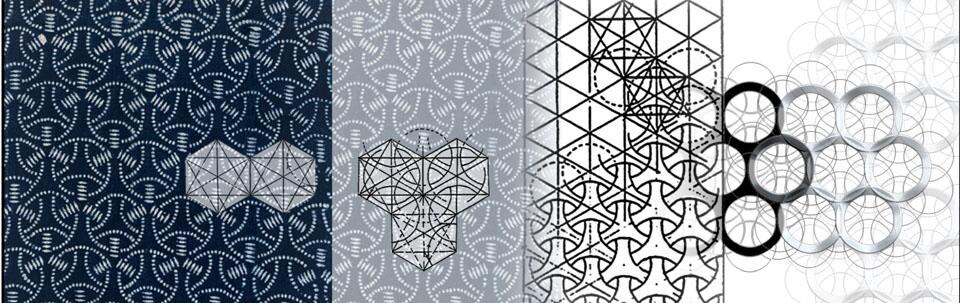

In the last two years at the Kuma Laboratory of Tokyo University, I have focused on traditional Japanese patterns, elements that are malleable, repeatable, adaptable to different contexts and capable of producing structural, energetic or aesthetic performances. Patterns—in the sense of geometric and ornamental motifs—have always been present in the architectural debate. In Japan, thanks to a gradual and ongoing development process, local craftspeople have managed to adapt and simplify their forms and aesthetic sense to attain, via constant design evolution, a degree of extreme purity. Each motif/pattern has attained a level of graphic perfection similar to that of symbols and icons, making its application to decorative-spatial use ideal.

Patterns permeate the Japanese aesthetic and define its important cultural, social and identity aspects. Each family had its own, called Kamon, a sophisticated and precise geometric composition. They were used as simple architectural features to divide space and, if integrated into a structure, unquestionably help define the image of a design.

In the Western culture, by contrast, even in De Re Aedificatoria, Leon Battista Alberti described patterns (in the ornamental sense) as the final component applied to bare masses to produce beauty and loveliness. He was describing architecture as a process that started with the mass and ended with ornament, passing via structure.

After being abolished from modern architecture because considered pointless ornament and not organic to the design process, patterns are today being seen by digital architecture as dynamei or potential generators of form.

With the advent of digital architecture and the ensuing set of theories that has emerged—generative and parametric design, numerical control machinery and digital manufacturing—we are looking at a new cognitive horizon.

In the attempt to synthesise culture and technology, traditional Japanese patterns—thanks to generative design—are emerging as organically architectural structuring elements. With my research, I try to determine a design process that safeguards tradition, interprets the contemporary and produces a new way of declining the intangible.

Salvator-John A. Liotta is an architect and researcher at the Kengo Kuma Laboratory of Tokyo University. He has lived in Japan since 2005. He and M. Belfiore edited the book 37 Domande a Toyo Ito.