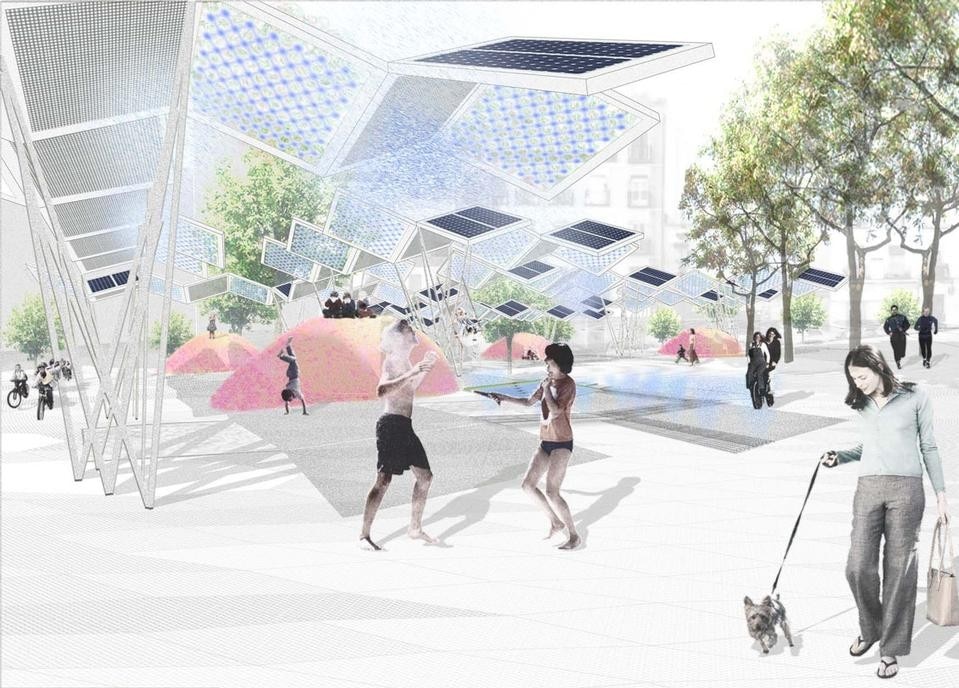

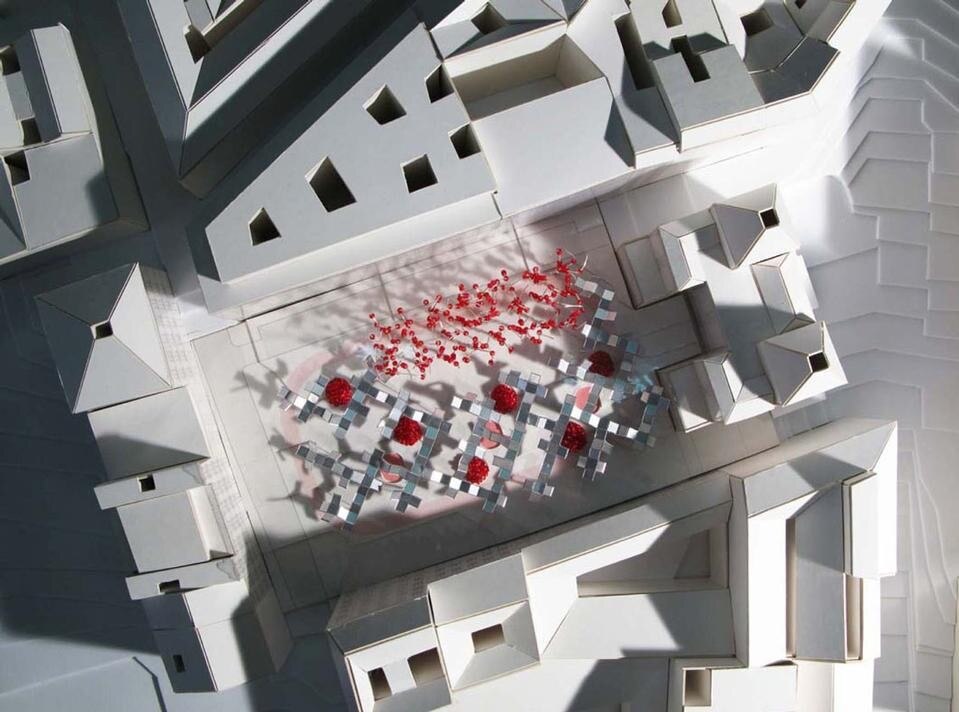

Plaza del General Vara del Rey in Madrid is a project by ELII elii oficina de arquitectura (Uriel Fogu, Eva Gil Lopesino, Carlos Palacios) characterized by the idea that the transformation of a public space into an "urban plant" for producing solar energy can gradually contribute to the city's economy. The project's first goal is to reverse common thinking about energy infrastructure as something outside, removed and invisible from the city in favor of a new idea of proximity and intermingling of activities, not only of places of consumption and (energy) production but also of life, play and rest spaces and energy production plants. The photovoltaic pergola becomes street furniture that can define space by providing shade or supporting a swing. In this project the visibility and acknowledgment of the photovoltaics is a key element in conferring a new spirit to public space and in disseminating a new energy culture: the culture of clean, renewable, widespread and localized energy capable of triggering dynamics of "re-territorialization" in the production and management of a resource that is fundamental for survival. In this sense, the project seeks to affirm not only environmental sustainability but also the social sustainability of an urban landscape that can integrate new technology and nature – plant and silicon photosynthesis.

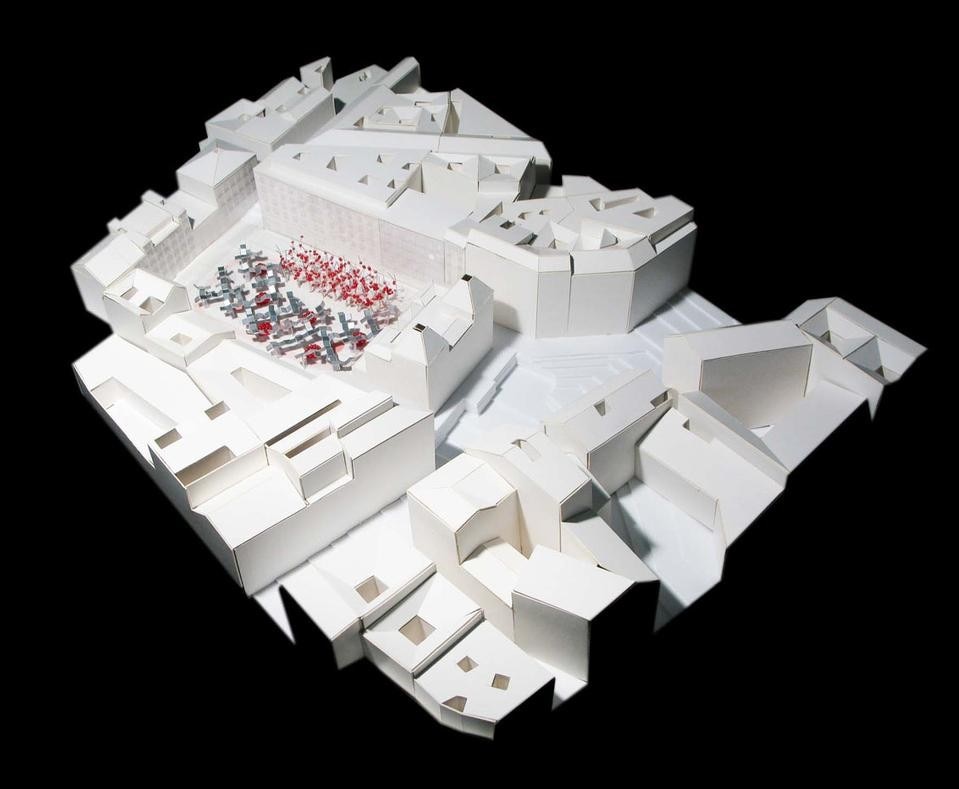

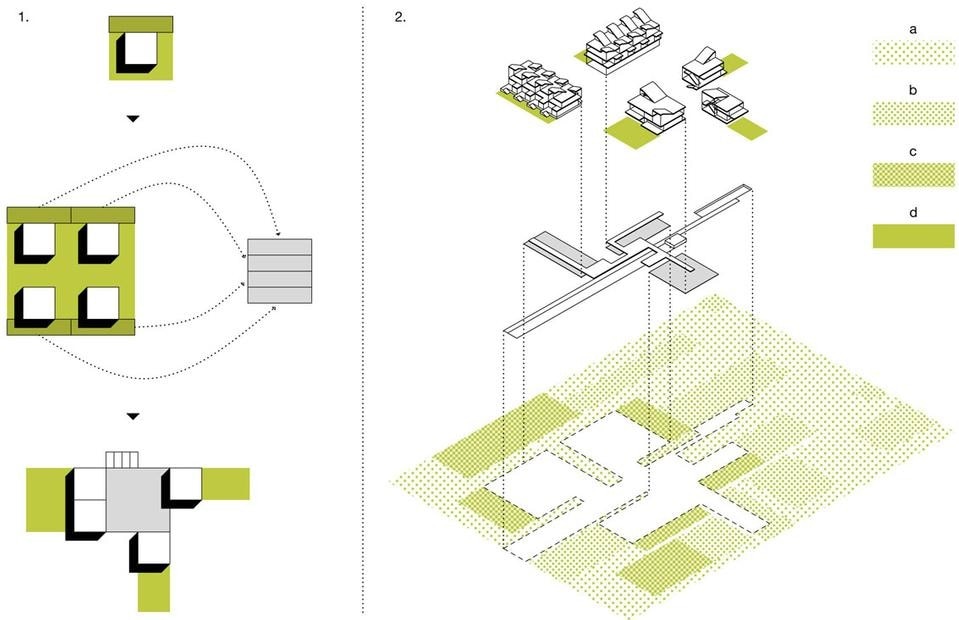

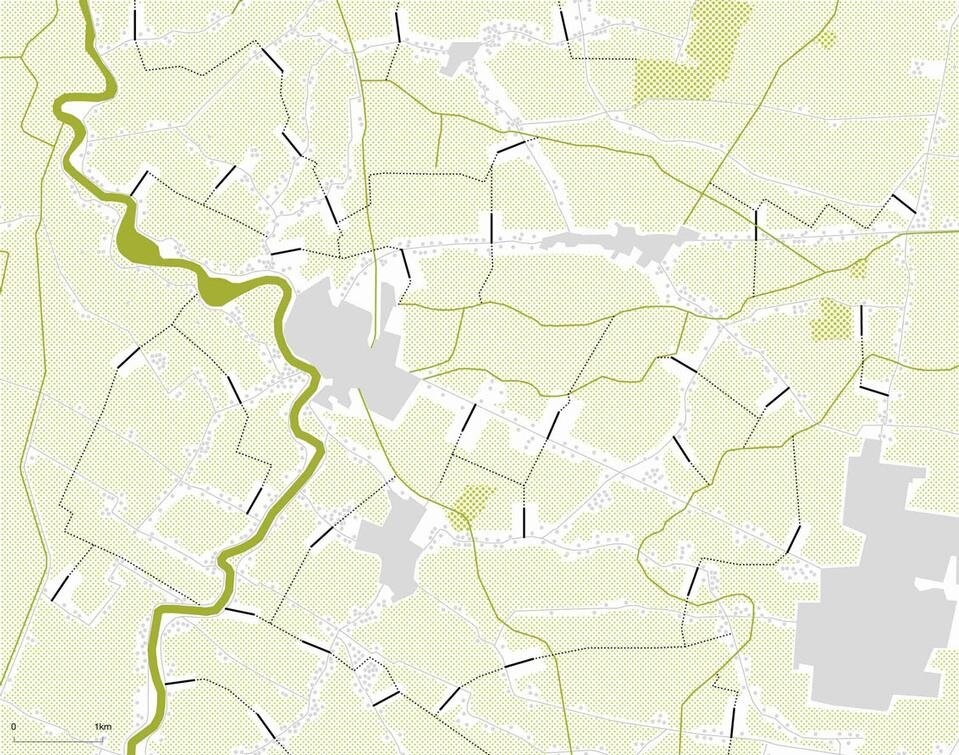

Neo-rural, collective, environmental is under construction. It was designed by the Frederick Zanfi studio during the approval process of the Structural Plan for Medolla, a municipality in the Emilia plain. The theme of this project is how settlements grow and expand in rural contexts where the urban area tends to grow along the main roads and occupy portions of agricultural land. The proposed model contrasts the typical urban model of filaments of isolated houses each located on its own lot facing the road by proposing a structure based on a system of open and public spaces around which different types of residential units can be organised. This system of voids (courtyards or barnyards) is integrated by a common area – "technology, agriculture and wetlands" – a large photovoltaic pergola, gardens, ponds and constructed wetlands for wastewater recovery. This system of residential aggregation, above and beyond creating a new social life based on sharing public space, also proposes a centralized and shared system for managing energy technology and sanitation systems. The independence of new growth from existing energy and sanitation infrastructure reduces urbanization and management costs for the municipality and makes it possible (due to the large size of the energy plant) for an Energy Service Company ECSO) to participate; by committing to the plant's design-construction and management for a fixed number of years (after which full ownership passes to the residents), the ESCO can underwrite contracts with third parties for energy supply. In this way, the response to the energy problem becomes yet another element stimulating "community" or sharing among the residents of the new settlements: thanks to its larger size, the collective system allows for greater efficiency and lower operating and maintenance costs. And so a "condominium" type translates into a benefit for individuals as an incentive to "live together." This project outlines a scenario for a new urban ecology that is both simple and complex, building strong social relationships, sustainable water management and energy integration between residential and industrial uses.

If we look at the three selected projects from an energy standpoint, it is easy to assert that they all work towards the same goal of energy self-sufficiency by using appropriate solutions and types of intervention on different scales. Solar technologies are part of the projects along with other elements belonging more to the traditional realm of architectural. It is like saying that in all three projects this choice lies in a domain that conceives of the building, or square, or the neighbourhood as a small – or even tiny – ecosystem whose metabolism is satisfied by energy provided by the sun. Not surprisingly, then, from a formal point of view, the use of photovoltaics is, for example, not particularly characterizing even when it is clearly visible. In other words, the use of solar technology is so mature that it is almost taken for granted thus leaving room for a more explicit architectural discussion.

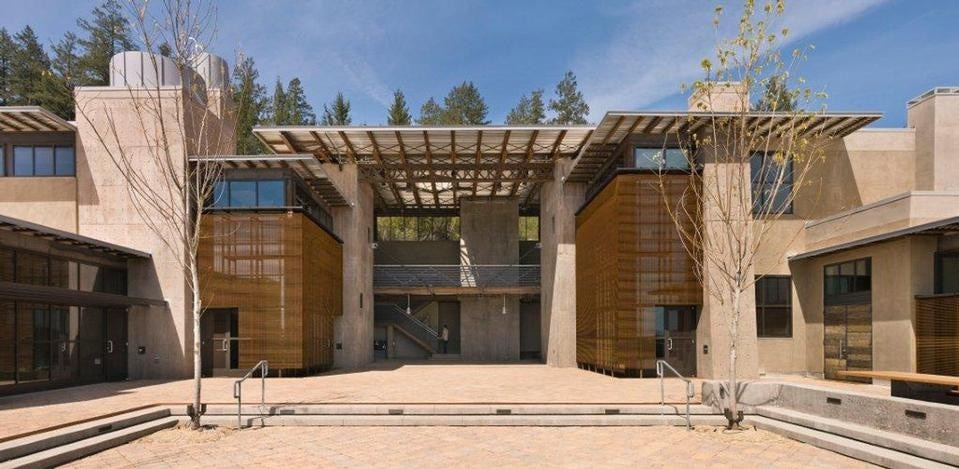

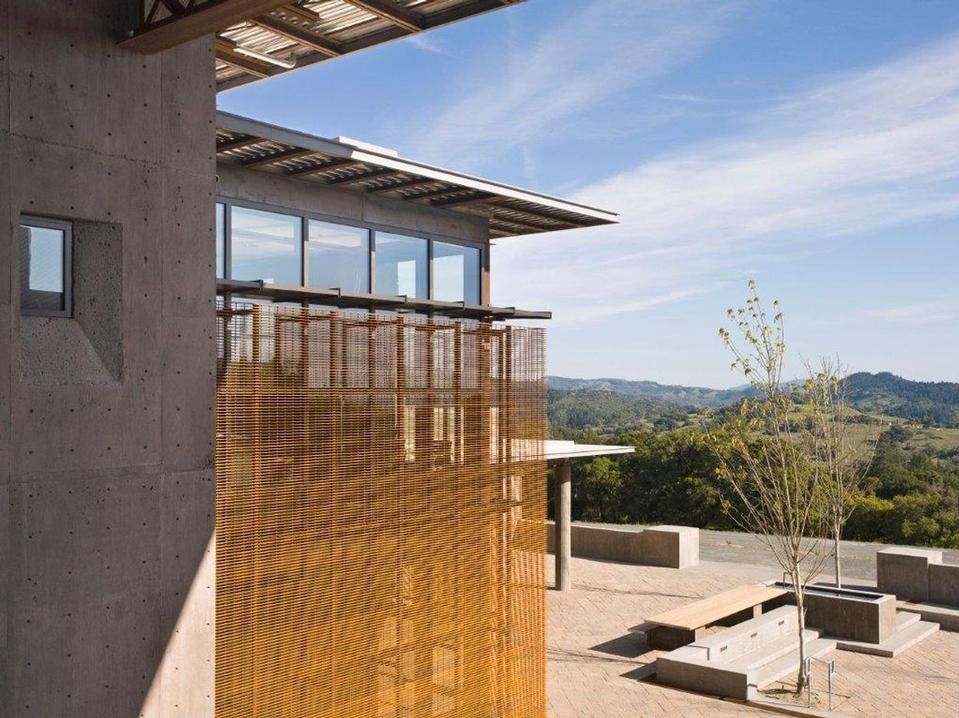

So, looking at the projects and their contexts again, it is interesting to highlight the energy logic that underlies the specific design choices. In the first case, Dwight Research Center, the building is isolated in an area dominated by wild nature, and is, perhaps just like the local native plants, an organism capable of consuming very little energy (LEED gold certification) producing only what it needs to function. In a non-urban environment, the building stands in relationship to nature and the landscape drawing from them the energy that it needs to work well and to ensure user comfort. In the second case, the Plaza del General Vara del Rey, the square is the heart of an artificial ecosystem that is different from the previous one - the city. Here the goal is not to "resist" – taking from the environment the most possible – but to dialogue with the surroundings through a system of flows of matter and energy. The need is not so much to meet the square's energy demands but rather to create a balance on a larger scale so that the energy produced by the square's large photovoltaic roof can offset the energy consumption of nearby buildings or functions. In the third case, neo-rural, collective environment, the vision is even vaster and includes an ecosystem that is small, but more complex, in which units that consume and those that produce are present and where the careful design of energy production can once again generate a feedback loop that subtracts entropy from the system thus triggering a virtuous circle. In all three cases, energy and architectural form seem perfectly integrated. In the California building, the solar canopy is homogeneous with the other materials used for in the building in terms of pattern and texture making it almost invisible. In the Spanish square, although the photovoltaic modules clearly denounce the use of solar energy, the entire roof can still be read as a texture whose basic element is the photovoltaic cell. This texture, by virtue of the knowledge that we possess today of the need to use solar technology, no longer seems, like some time ago, extraneous to the traditional repertoire of materials and forms of architecture. In the Italian neighborhood, the only element that marks the presence of photovoltaics are the roofs of the individual buildings – surfaces that slope to find the best solar exposure maximising energy production. Alessandra Scognamiglio, researcher and architect (ENEA) and Marialuisa Palumbo, architecture critic