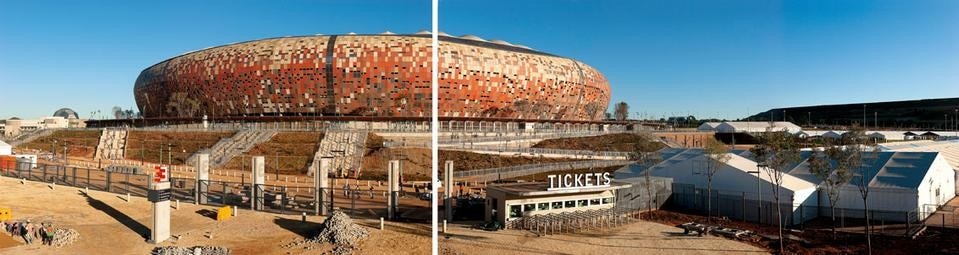

Soccer City has a large circular footprint that officially symbolises a calabash, but that equally functions as a strong, neutral form, a stabiliser in the dynamics of change. The striking external skin of Riedel panels covers the remnants of a utilitarian stadium built in 1987 at the height of the struggle against apartheid. The old stadium served Soweto's passionate soccer fans and symbolised the apartheid state's reluctant concession that the township, originally conceived as a labour dormitory, was indeed their permanent home. In 1990, it was where Nelson Mandela chose to celebrate his release to a jubilant, overcapacity crowd.

Twenty years later, the stadium has been re-engineered around another significant event. Originally designed to separate out the emotion and crowds gathering around soccer and politics, constructed in an urban wasteland in the most functional way, it has been rejigged to become a centre, a social, economic and mediated hub. Its location inverts Johannesburg's tendency to develop northwards, away from its townships. The redeveloped site now connects with Soweto, the city and beyond with new rail, rapid bus and vehicle systems and fibre optic cables.

The stadium's broader precinct is largely undeveloped, its plinth still surrounded by sand dumps and veldt and an overlay of tents, containers and fencing that recall the original mining town. FIFA's presence is an ephemeral layer that comes and goes in a month, an event city built around the media, financing and global branding. This "festivalisation" of urban development is both contemporary and controversial. There is growing public disquiet about the ways in which prestigious structures were rushed into construction for a mega event held in a developing country where the most basic spatial needs remain unmet.

The irrational spending around the event was excused by the game's popularity in South Africa, where it developed during apartheid largely as a black sport. In the so-called New South Africa, the World Cup has been marketed to help forge a singular national identity, particularly through support for the national team. Alongside the questions around priorities and costs, there is much pride in the country's capacity to achieve the instant modernisation of its cities. The two design teams – Boogertman Urban Edge + Partners, and Populous – are skilled practices that excel in fast and economical delivery. They describe themselves in terms of their extensive technical experience and their working process as one of collective decisions and above all pragmatic thinking.

The stadium now works smoothly, managing the vast flows around the big event, from recycled water to circulation along the ramps within the outer skin, and the outward flow of images and commentary from the media. As a tool, it promises to mediate between its African site and the global village without hitches.

In this role, the stadium mirrors the game of soccer itself, at least as FIFA has defined it. It engages with contemporary techniques to access and promote a series of fragile human qualities, particularly those, like play, that are located within the body's deepest affective, physical makeup. Many people react viscerally to the stadium: with joy, pride in its making, ossession and awe. It is as if an apparently mechanical construction process has admitted a ghost, a spirit that infuses the object with a non-rational presence. Perhaps this quality lies in the materiality of the building, how the oxides in the panels echo those in the earth dug around the site. Or in part in the promise of the open precinct around it, which heightens the stadium's ambivalent nature as either a fetish object or central place.

Time, and the strategic engineering of both events and place, will finally determine the stadium's value. The space in and around the stadium, accessible from all parts of the city, and the return of global investment to its source, could create sites for new and transformed community institutions and for platforms that manage and market the products of an emerging economy. The stadium and the World Cup final itself could provide an image for this engine of change, of a vast and creative structure rotating around a simple field, with a game played by sportspeople who mix rules and inspiration in equal measure. Hannah le Roux

Soccer City Stadium, Nasrec, Johannesburg, South Africa

Architects: Boogertman Urban Edge + Partners in partnership with Populous (Bob van Bebber – Project Director: Boogertman Urban Edge + Partners; Piet Boer – Senior Associate & Project Architect: Boogertman Urban Edge + Partners; Damon Lavelle – Associate Principal: Populous)

Contractor: Grinaker-LTA/Interbeton

Crowd modelling: Steers Davies Gleave

Structural engineering: PDNA/Schlaich Bergermann & Partners

Civil engineering: Phumaf

Acoustic engineering: Pro Acoustic Consortium

Electrical engineering: Advoco

Electronic engineering: QA International (Pty) Ltd

Fire engineering: Chimera Fire

Mechanical engineering: Dientsenere Tsa Meago (Pty) Ltd

Landscape design: Uys & White

Quantity surveyors: Llale & Company /De Leeuw Group

Site area: 254,725.96 m2

Total stadium seating: 88,958

Built area (footprint): 160,284 m2

Cost: 3.38 billion ZAR

Design concept submission: March 2006

Tender period: November – December 2006

Construction: February 2007 – March 2010