The only other passenger in the cabin was an 11- or 12-year-old girl, who was fast to answer Luis's questions as we passed over a basketball court 20 metres below. "They shot a boy here the other night. Did you know him?" "Yes, his friend shot him." "Do you know him too?" "Yes." "Aren't you afraid to go up here alone?" "No, this is my neighbourhood." "But the boy who died was from this neighbourhood, too." "Yes, he was born here."

In the cafe where we met before boarding the Metro Cable with Hubert, Luis spoke candidly of the Barrio as an error de planificación. He represents the most informed portion of Barrio inhabitants. Even in jeans and a T-shirt his appearance is groomed – short, steel-grey hair and a few blingy rings on his fingers, possibly indicating his non-attackable authority, at least in his neighbourhood. He doesn't realise his contradiction, which I silently noted to myself, as he explains that the barrios are very old, having began to spring up when immigration from the countryside started in the late '40s, and they've never stopped growing since. So it is not a planning error, but just another example of capitalist no regulatión, if indeed capitalism was ever interested in regulatión. The barrios have gradually encircled the middle-class city, practically besieging it.

How many times has contemporary architecture changed "styles" or "trends" in the past 50 years? Modern, late modern, post-modern, neo-modern, critical regionalism, deconstructivism, genericism... while in the Caracas barrios, the barriadas of Lima, or the shanty towns of Mumbai, nothing has changed in the way of building and living, if this is living: an inconceivable condition for whoever has not seen it before.

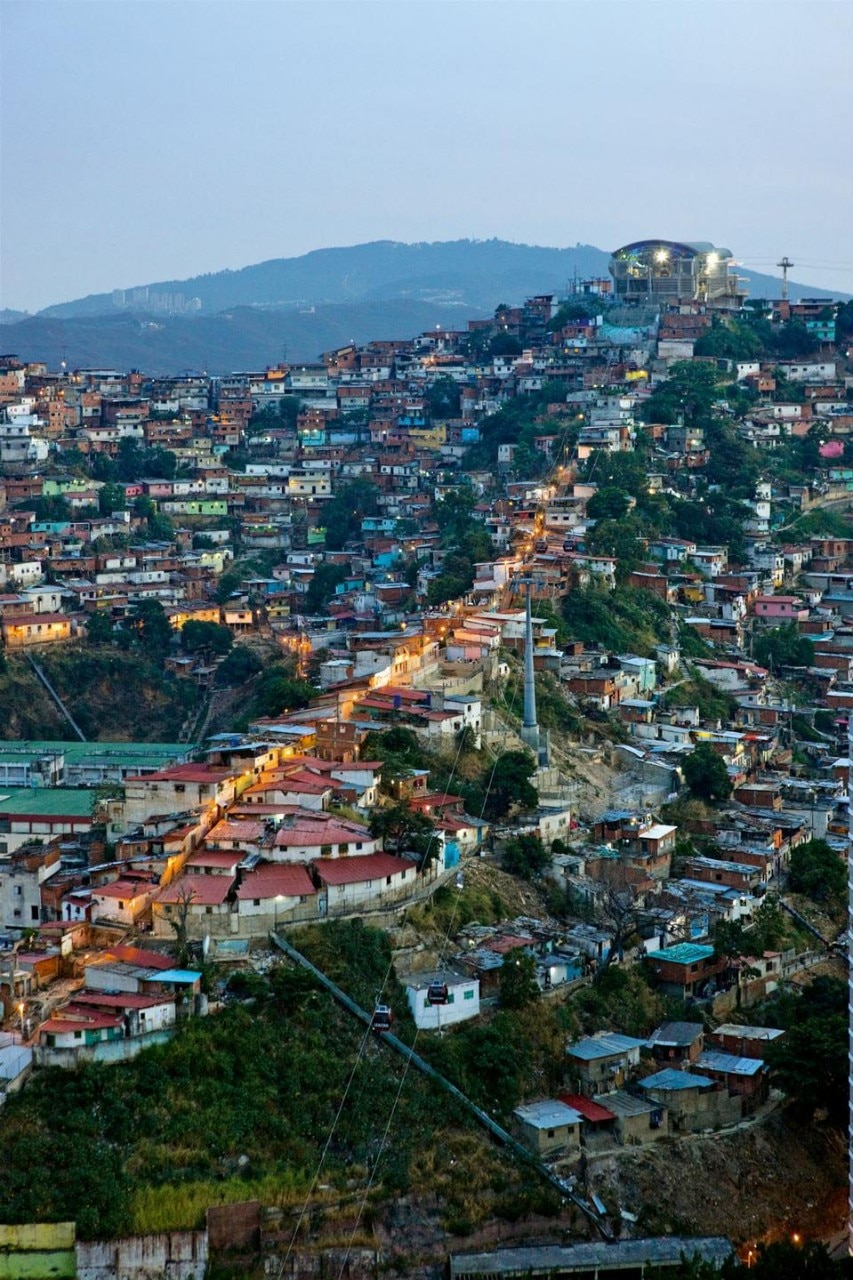

After a long ascent on foot (the only way to reach places not yet served by the Metro Cable), we finally arrive at a small clearing slightly larger than the ones in front of the houses. From this "terrace" of Barrio 903 (its altitude in metres), there is a better view of the "informal" landscape, as Klumpner and Brillembourg elegantly call the Barrio, where the laws of gravity have been subverted. Here, buildings that shouldn't stay standing somehow manage to do so, just like the circa 200,000 inhabitants who succeed in living here against all odds. Nobody should have to live without water, electricity, sewerage, hospitals, schools, or even a place to go and pray for someone to remember you.

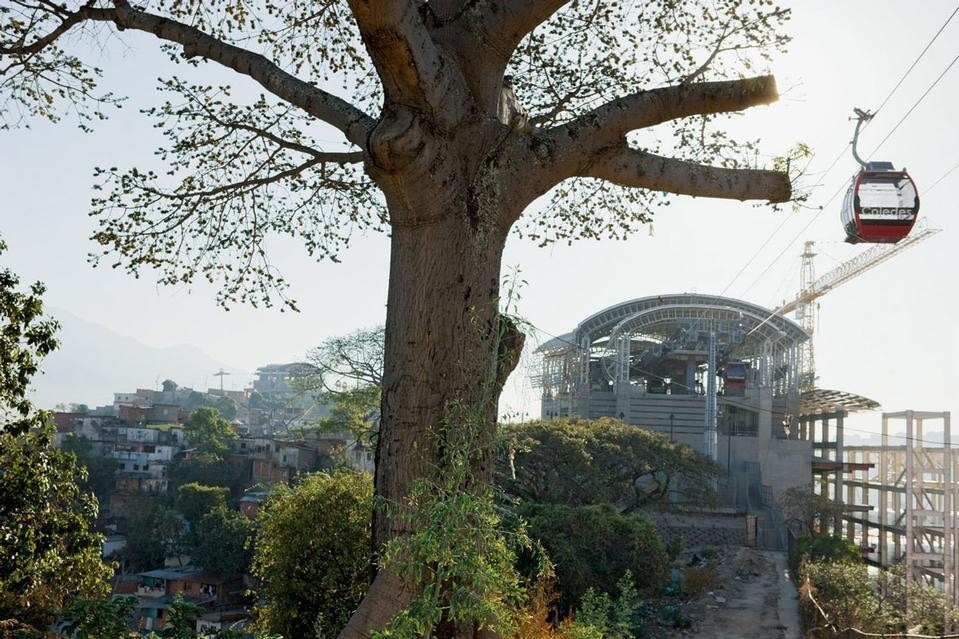

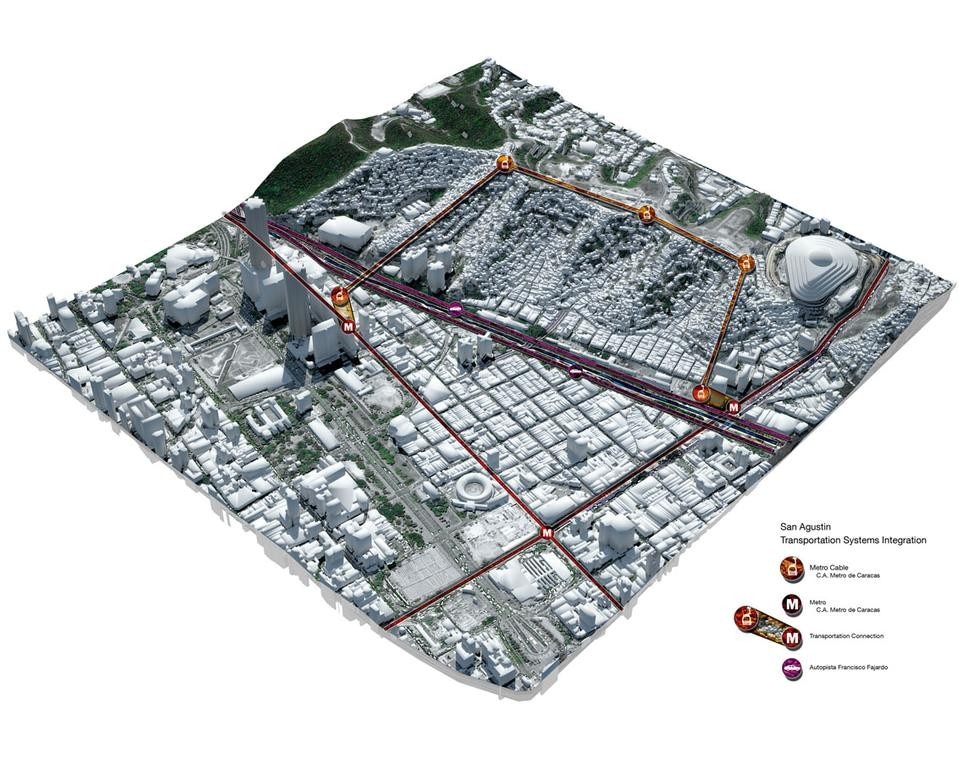

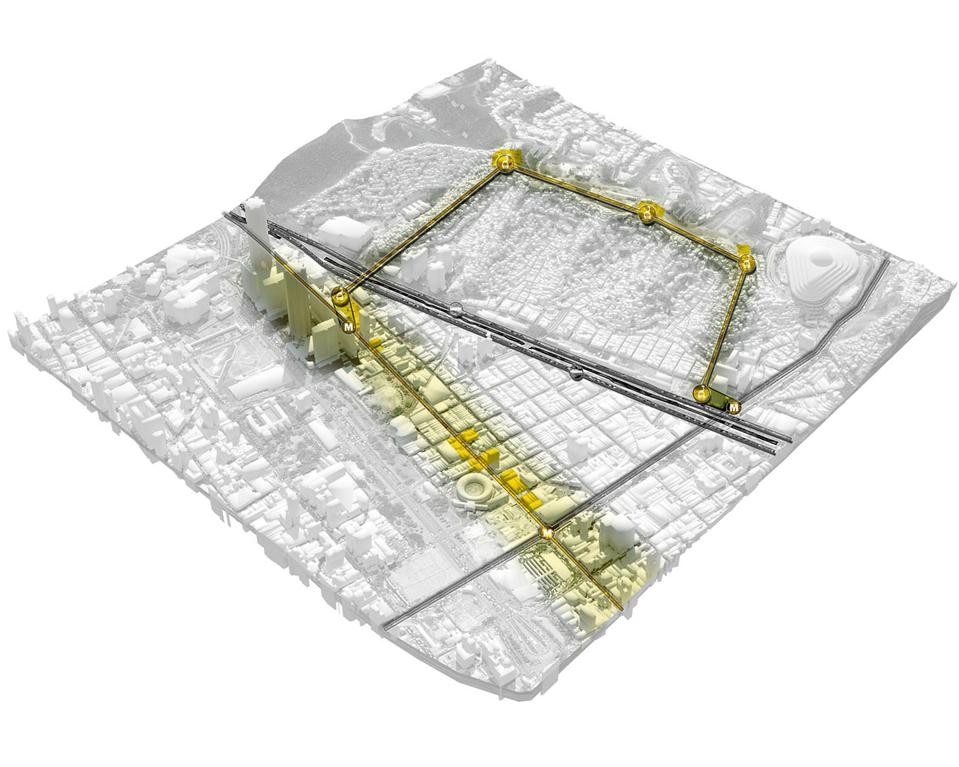

Someone must have heard a few prayers made in some anonymous place, and sent Klumpner and Brillembourg to work here. The design concept is simple, pragmatic and anti-demagogical. Is it feasible to restructure the building situation of spontaneous slums where hundreds of thousands of people live, about 50 per cent of Venezuela's population? Clearly not. Hence the idea of a transit system connecting the Barrio to the valley – both a public service (for those who work in the city, for the elderly who are unable to visit relatives due to the 2.5-hour walk that separates them, for children who want to get out of the ghetto) and a tourist attraction (why not?): a connection between urban formality and suburban informality, an opportunity for small renewal projects. So, on 12 April 2007, a citizens' council of the San Agustín community defined the social programme that will accompany each of the five Metro Cable stations: San Agustín, El Manguito, La Ceiba, Hornos de Cal and Parque Central will also give the Barrio a gymnasium, a multifunctional hall and a social centre. The rest – the mission of achieving construction – was left to the designers, who by then had become one with the locals.

Some messages cannot be conveyed with words, and the signals that Luis sends to the people of his barrio are unspoken and implicit. Looking at these architects walking with me and saying hello to people like I do, one notices they have no expensive shirts or hand-sewn leather shoes, no Rolexes or Porsches. Hubert's suggestion was useful: "Just take off the fanciest things." Discarding the superficiality of our objects for complicated rituals can be good for the heart. It may feel less broken after seeing rats as big as lapdogs dancing atop the garbage that is dumped from the heights of the hovels; after repeatedly hearing the jocular salute between Luis and the homeboys – permanently waiting for some unknown event outside their houses – as they mimic a few shots ringing from a pistol; after listening to a teacher who looks too old for her years, but has a room as big as the conference room at Domus, the only school for the Barrio children, as she proudly shows their assignments and continues to mark them.

For those who have forgotten that pop is the essence of all that is contemporary, and that the distance between project and icon is short, there is the image that I see from Hubert's car on the way back. On the wall of an underpass, in that city centre of sorts, a new mural of ceramic mosaic has grown, Trencadís as they'd call it in Barcelona, where it embodies the nightmares of Jujol and Gaudí. It portrays a young, curly haired Simón Bolívar showing a boy the Metro Cable cable cars flying over the city, over smiling verdant plains, under a blue sky with clean air: a socialist utopia of Caracas that for now is still confined to government speeches and the artist's imagination. In reality, this ville fatale is more like a cross between Los Angeles with its interminable freeways that always bring you to the same place, basically nowhere; Rome in the '60s, when the only infrastructure was built for a future that never came; and Havana, where I've never been, but which must have similar broken-down buses, the same inhabitants who call everyone hermano, the same fear of not knowing what will happen tomorrow, or knowing that nothing will happen at all.

So I return to my five-star hotel and begin to write this article at a table in the dining room. I write because it's what I can do best. I write so I don't forget the Barrio of San Agustín, the girl on the Metro Cable, Luis Cerpa, his brother, and all the inhabitants of Barrio 903. I also write so as not to forget Hubert Klumpner, Alfredo Brillembourg and their shiny, generous utopia, which has become reality, at least for once.

Founded in 1993, Urban- Think Tank is headed by Alfredo Brillembourg and Hubert Klumpner, both teachers at Columbia University in New York and principals of S.L.U.M. Lab, an academic research studio.