You have been working along the international border between San Diego and Tijuana for a long time, trying to set up new forms of collaboration with institutions and jurisdictions, I mean, for example, the “micro-policy of intervention” aimed at transforming suburban areas into social systems that can anticipate, organise and promote social and economic exchange. How did these projects come about?

Teddy Cruz: As an architect I have always tried to reposition myself in the context of the city, to fully understand social, economic and political dynamics. What is more, conflict as an opportunity represents a central aspect of my work. Having said this, what has fascinated me is to witness the transformation of the city by immigrants, generating informal dynamics that suggest a very different idea of the city to the one we usually hold.

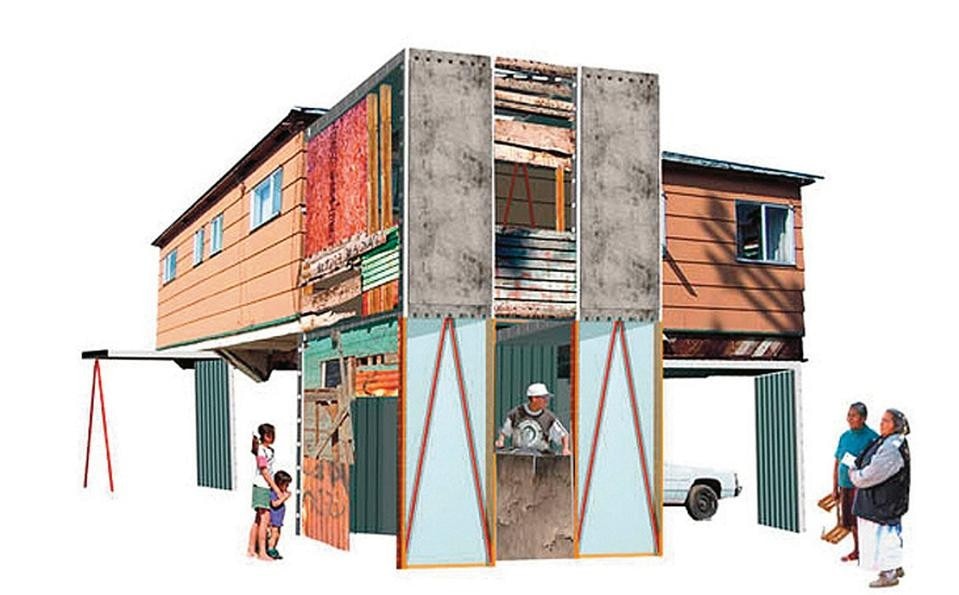

Through my work I have been closely involved with the role that immigrants play in producing a different image linked to the city. In the border territories where I’ve worked, there is, for example, a flow of people that try and enter the US from Mexico and that move therefore from south to north, while in the opposite direction, from north to south, a flow of waste is generated that goes from California towards Tijuana, into the shantytowns, so much that you could say that the new periphery of Tijuana, new informal suburbs or slums that spring up from one day to the other, have been built out of the waste of San Diego. Migration of people on the one hand and on the other transfer of waste: these invisible flows were the inspiration for my work along with the idea that in these migrations there was a hidden value that could generate a different idea of economics and politics of the city.

Do you think that these dynamics can be identified also in a broader and more global system?

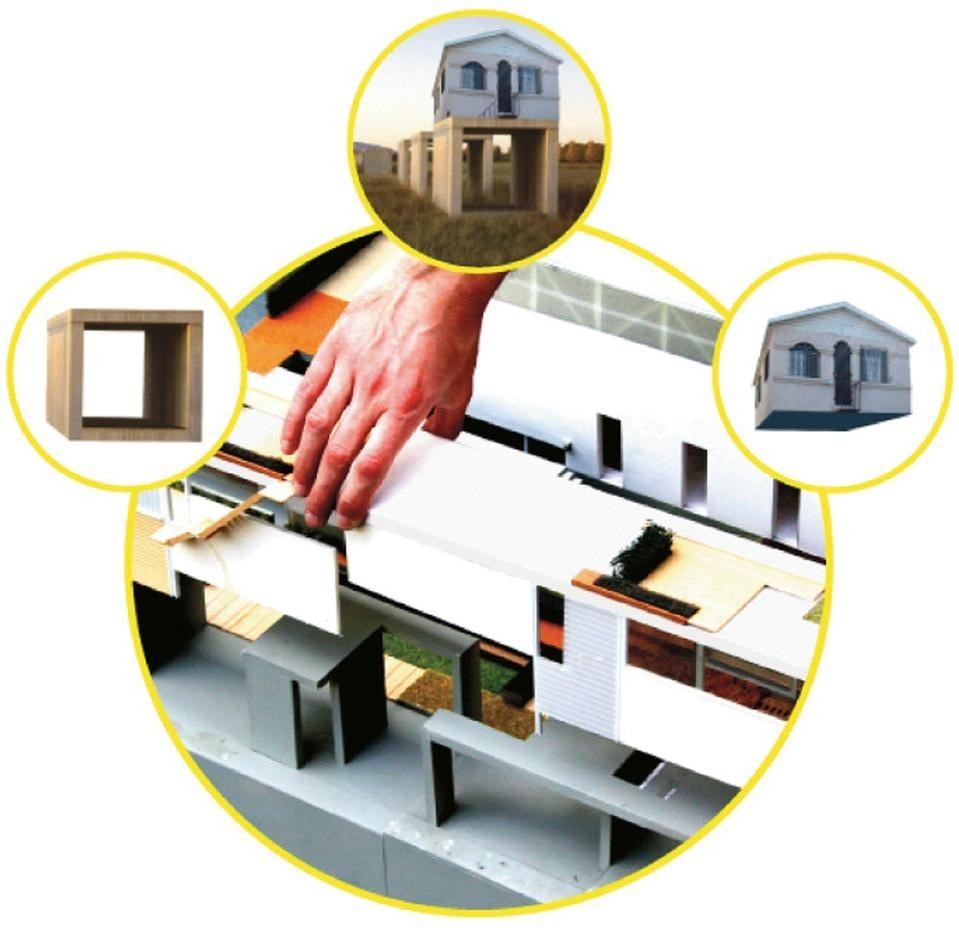

T.C.: Seeing the existing crisis, I think that now more than ever we are witnessing the extension of certain phenomena on a bigger scale. The development of the city cannot follow just one recipe and hyper-development can’t be the only answer, we need to rethink the meaning of infrastructure, social housing and public space and we need to look at other dynamics that are on the ground like social networks. The house shouldn’t be seen just as a dwelling unit, it can be more than shelter, it can be transformed into an economic engine to rethink modes of production and labour in the community and can be incorporated in a new idea of infrastructure, probably much more sustainable. I think Latin America is worth mentioning for this while a model that could be exported to other places is California, for the way that immigrants have retrofitted the suburban landscape into more complex settlements and alternative economies.

Why do you think that Latin America is a good example?

T.C.: Because they have realised that the city contains a wide range of ideas about informal urbanism and alternative economies that can exist alongside the models typical of large, urbanised areas. I think that some of the most interesting mayors like Jaime Lerner in Curitiba, or Enrique Peñalosa in Bogotà or Sergio Fajardo in Medellin are not interested in perpetuating an idea of city but they realise that there is an amazing potential in absorbing some of these informal dynamics that are created spontaneously in inhabited areas and are able to transform them into more formal institutions, putting into action a hybrid idea of formal and informal infrastructure at the same time. In this case, I think that these mayors one, move away from a certain dissatisfaction about the north American style of globalisation and two, they have understood that the informal economy is a way of producing and as such can be very effective. We have to stop looking at abundance and be able to look at those places in which scarcity is the reference, places where some of the most creative ideas emerge, places where a lot has been done with very little.