Recent stereotyping (still to be disproved) relegates architecture magazines to mere newsletter status. For these fossils from the Gutenberg era, which are as heavy as they are beautiful, and too impractical to slip onto the Web, the choice between form and content instinctively goes straight to the former. Content, message and interpretation all come later, if at all. In the race for a scoop, which has become an arduous task in today’s mass-media architecture market, critical and dialectic substance is largely manifested by varying degrees of celebratory graphic design, and a choice of either artistic/sculptural/spectacular or anthropological/sociological/journalistic photography (under the motto les extrêmes se touchent).

The ideal masterpiece of this latter conception is a photo of an ugly building, designed by a well-known architect, taken through the closed and even slightly dirty window of an automobile driving through the rain. Caption: “Architecture criticism fuses with photo styling.”It might seem irreverent to precede the analysis of a place of worship with this annotation. But at the extreme northern boundaries of the Old World lies the result of an Apollonian exercise in the beauty of simplicity, and now that the Design Economy is making its way in the world as one of the last chances for the West’s survival, it would be deceitful to pretend that in this case the two specular objects (the constructed building and its publication in magazines) are not part of the media phenomenon.

As such, they require a less naive look than the one that we have become accustomed to reading in interpretations of contemporary architecture. It is not by chance that many weeklies have been literally fascinated by another recently built monastery in Novy´ Dvur, designed by John Pawson. It was naturally reported on with much more blasphemous gossip (monks in search of inspiration at the Calvin Klein showroom in New York) than truth about the project, which is itself a pathetic minimalist extension to the rituals of monasticism. The Tautra Maria convent does not escape media market rules either (at least in the moment it is published).

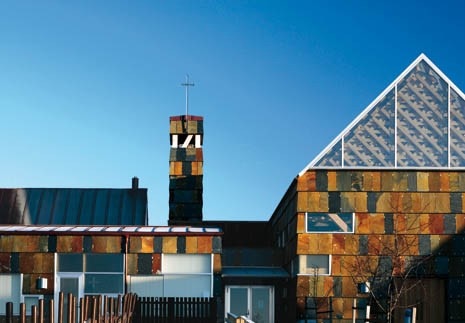

Recently finished, it won the Forum AID Award promoted by the homonymous Scandinavian magazine, which documented it in a concise but effective article. It immediately received another prize (the International Award Architecture in Stone 2007), throwing its designers into the perverse media circuit where those who remain excluded are destined (if they are lucky) to be discovered in a few decades. It is sufficient, however, to deepen one’s knowledge of the architects slightly to find that Jensen & Skodvin are no novices at designing for divinity. Their Lutheran church in Mortensrud (2002) already gave us an impression of the oppressive weight that faith has for believers who live in such an agnostic society as the Scandinavian one. An efficient metaphor of this is the inverted heavy/light structure of the building, a large opaque volume placed upon a transparent base. But it is one thing to design a customarily autonomous object like a church (see Ronchamp, where Le Corbusier finally got to play the artist instead of tediously defending Modernism) and it is quite another to conceive an entire small community such as a monastery, where the inhabitants are destined to live for at least the rest of their days. So Jensen and Skodvin commenced a complicated dialogue with the nuns, perhaps to understand what drove them to take refuge on the little island of Tautra. Surely to construct a citadel of God, as minuscule as it might be.

The convent’s history, told on the friendly website www.tautra.no, could easily serve as inspiration for an old-style Woody Allen movie. In 1999, the Cistercian nuns of the Our Lady of the Mississippi Abbey near Dubuque, Iowa had the illumination to found a convent in Norway on the island of Tautra, or rather refound it, given that the site already hosts the ruins of a 13th century abbey. Five sisters left Iowa for Trondheim, together with two Norwegian sisters from other monasteries. In 2005 construction began on the Tautra Maria, which was finished and consecrated last year. Careful reading of Ellen van Loon’s presentation of the project for Forum AID reveals that the relationship with this very unusual client was anything but smooth.

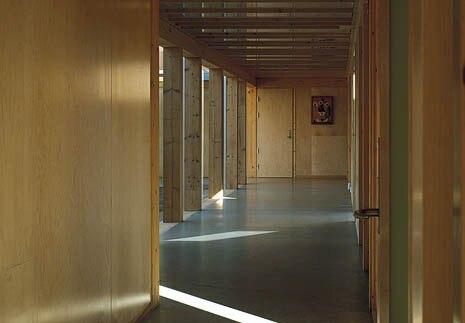

The architects sought to give the Cistercian sisters a complex that guaranteed an ascetic compositional structure (its plan is a simple rectangle) but lent more freedom of movement to its inhabitants. True to Cistercian rules, which although involving a lifelong vow are very open towards the world (the nuns of Tautra earn a living by producing and selling natural soaps while those of Dubuque make mail-order candy), the clients were able to reduce the surface that the designers had proposed by 30 per cent. The space reserved for walkways was practically eliminated in order to create miniature gardens for the enjoyment of the recluses. Jensen & Skodvin (particularly project leader Jan Olav Jensen) must have made virtues of many necessities, succeeding in obtaining a few concessions pertaining to materials used for structures and finishing. Here, too, there was no lack of obstacles. For instance no wood veneer was to be used on inside wooden walls because an excessively vibrant pattern could disturb concentration in prayer.

Thus it is mostly in the structure and the outer shell of the convent that the designers were able to give their best (nuns in prayer don’t see those parts). The building’s outer facades carry one of the most extraordinarily intriguing surfaces seen in architecture in recent years. A collage of thin stone slabs with different colours (blending perfectly with the Nordic landscape) feature a dominating ash-yellow shade reminiscent of primordial earth: “Ashes to ashes, dust to dust”. Although Jensen and Skodvin chose to avoid facile symbolism, it takes little imagination (maybe one just needs to have had a Christian upbringing) to see the intricate wooden beam structure that makes up the roof of the church as an infinite multiplication of the arms of the cross upon which the Messiah was crucified.

An immense non-figurative crucifixion where everyone – from the nuns who seek refuge from the horrors of the world in Tautra, to the simple media-voyeur and the rest of us sinners – can imagine his/herself suspended between earth and heaven, waiting for God to give impossible salvation, at least until the end of the world. S.C.