Frédéric Edelmann

Completed under precipitate conditions, the Musée du quai Branly was warmly received by the French public and media, but very coldly indeed by most of the foreign press, notably American, German and Spanish. Having embarked long ago on an unprecedented communication campaign, the French press revealed itself to be globally complacent in rallying to the major televised media consensus towards official cultural events. In a globally hackneyed country unfit for the initiative, the birth of the museum has therefore been received with a benevolence far removed from the surprised admiration aroused by the Arche de la Défense, the icy astonishment elicited by the François Mitterrand Library, the aesthetic fatalism engendered by the Opéra Bastille, the lyrical delight with the Cité de la Musique, or the dignified respect for the Grand Louvre.

Le Monde was no exception to this trend. Indeed, without actually stooping to censorship, the prevailing mood induced its staff, technical or editorial, to erase anything that might have preserved the ironic tone of what remains of this article. Thus I proposed what I thought was a relatively anodyne, but explicit title, as far as the regressive aspect of the overall project was concerned: “Exoticism at the service of ethnology”. It was removed in favour of a chorus of praise that looked good in the article, the voluntary silliness of which, however, was effaced. Doubtful about the sense of the museum, critical (severely so) of its hybrid architecture, amused by the aesthetic leanings of a museography that seems to find its sources in the Musée des Arts et Traditions Populaires (now closed), in antiques fairs or in the Grévin museum, I nevertheless found myself wondering about the dogmatic virulence of certain reviews.

The museum was not really finished either at the time of the press conferences or even at its inauguration, and most of its exhibits were still invisible. The project’s intellectual pretensions are ill suited to its propensity as a whole to cling, to the point of vulgarity, to the colours, and even the forms, of high fashion. And worse still. In these criticisms there is a call to “good taste”, to conventional norms that have once again become fossilised after the “liberating” passage of Koolhaas, Gehry, Herzog & de Meuron… A wavering norm, like the forms it authorises, whose limits are adroitly defined by the annual distribution of Pritzker prizes. Hybrid, composite, coloured, mysterious and joyous, Jean Nouvel’s building has in effect set itself beyond the usual time and canons of contemporary architecture, as if to escape (with a successfull, although outmoded technique) the reticence, the rejections even, that so often accompany radical expressions of modernity. Would the best-known French master avoid criticism, were he to become the Robert Hossein or the Luc Besson of architecture? Let his admirers be assured: no matter how seductive and theatrical, Nouvel is still Nouvel. But he benefits from a twofold movement. On one side, the public has grown accustomed to his tricks and to his manner of applying a fresh vocabulary to each new design.

No need to fear the radicalism of the Lyon Opéra any more, knowing that he can also come up with the limpidity of the Art Centre in Lucerne, Switzerland. And as for the architect, he has shed his taste for provocation, or to be more precise, as in the case of the quai Branly he has donned all the trimmings that reflect the taste of the period: ecology, green space, the play of light, alternately brut and high tech materials, etc. And here, in Paris, his work ends up melting into the lure of tropical savannahs and the steamy heat of equatorial forests, even if geographically the museum’s scope is wider. Already, from the Seine, the museum escapes the eye.

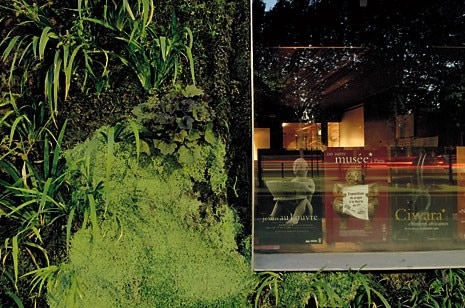

Its image is (or will be) softened by the tree-lined embankment and avenue, as well as by a large glass screen – a device that scored a huge success at the Cartier Foundation in Boulevard Raspail. A second curtain of trees, planted by the landscape gardener Gilles Clément, will, with time, further blur the building’s image. The only part of the building situated to the right of the avenue, draped with creepers and already for the past two years inhabited by the museum’s curators, enhances the magic power of trees to disguise a building, as Virginia creeper or wisteria do in northern Europe.

The building – and must we blame him for it? – is formidably decorative, inasmuch as theatrical décor can conjure up the atmosphere of a play or opera. But, perched in an artificial canopy, there is also this paradoxical virtue of suggesting an exotic aesthetic, highly evocative of the colonial past. And so it carries the weight of history, while it is, or should, assert itself as the receptacle for objects charged with symbols and bearing functions beyond their formal dimensions. One can understand the desire to reconcile (albeit under constraint) the supposedly pure tenets of anthropology and the supposedly futile ones of aesthetics. But it has to be noted that the operation (poorly) disguises the classifiable mercantile aspects as regards history in a picturesque mood, and the sanctified ones when it comes to the present, through a policy of diversely consenting donations.

Obliged to surf these paradoxes, without restraint in the architecture, but with brio in its stage designs, Nouvel handles a myriad of techniques imported from the world of entertainment and from the phantasmagoric museums that have so bewitched the public: with curtains, reflections, direct and indirect lighting, shadow… Pretend though he may, Nouvel is not fooled by his own choices. Aware of having to meet a complex and geographically heterogeneous demand, he outwardly and inwardly creates a composite project. Each part of it retains its visual autonomy, but as a whole it is feigned and contrived, after the manner of its north windows, heavily coloured with vegetal motifs, and in this respect as outmoded as an oilcloth. In passing, he fondly loots the Paris landscape and spirits away the riverside scene, Palais de Chaillot included, to satisfy the needs of the immense terrace which “composes” the architecture of the roof, and frames the ectoplasm of the Eiffel Tower in a virtual showcase: an ordinary window.

A garden metaphor

Interview with Gilles Clément by Manuel Orazi

If there is a quality which unites the not many gardens designed by Gilles Clément it is that of raising questions. In any case and by virtue of the sometimes contradictory heterogeneity of parks like the André Citroën in Paris, the Île Derborence in Lille and the Domaine du Royal, Clément is not easy to place as a theorist and landscape designer (see Domus no. 890, pp. 56-63). Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of his work is his scrutiny of nature on the basis of authentically and literally global criteria and principles, on a par with such enlightened sages as Alexander von Humboldt, another naturalist and traveller. Concepts like that of the Planetary Garden and Third Landscape, around which almost all his works of the past decade rotate, call into question the whole of mankind and presuppose movement, as Filippo De Pieri has rightly written. (M.O.)

Manuel Orazi Why do you think Jean Nouvel approached you to design the gardens at the quai de Branly museum? In the past you have done projects for parks, but never a garden for such an important building, right?

Gilles Clément I had already had occasion to work with Jean Nouvel on the (lost) competition for the Beijing opera. We also have the same publisher (Tonka) so Jean knows something about my work. In the past I have had occasion to work on sites marked by certain prestigious buildings, such as the Valloires gardens in front of the big Cistercian abbey there, as well as the Bois gardens in front of the chateau, and gardens for the Arch opposite the Arche de la Défense.

Manuel Orazi In the 1999 competition project for the garden, a simple flat lawn had been planned. So the project later underwent a radical evolution, from the altimetric point of view and in its variety of vegetal species. Could you explain your reasons for altering the design in such a major way? In particular, what role did Jean Nouvel and Emma Blanc (project director at Nouvel’s office) play?

Gilles Clément Emma Blanc (a former student of mine) and Jean Nouvel played no role at all in the conception of the garden. I had to alter the reliefs, and I also had to exaggerate them due to the creation of an immense and very conspicuous waterproof caisson, which surrounded the whole garden and served to protect the basement collections against flooding from the river Seine.

Manuel Orazi The slopes were created by embankments but also with polystyrene panels. I believe this solution is in contradiction to the principles of your Manifesto of the Third Landscape. Is it a compromise or more simply a technical adaptation?

Gilles Clément This garden site as a whole is a total contradiction to my ideas. I had to accept the technical propositions in order to avoid putting too much weight on the paving of the basement collections.

Manuel Orazi Around the side opposite the Seine your garden becomes a pond, and even incorporates certain architectural features, such as the balustrade which vaguely resembles a wattle fence while giving the impression of not being an actual barrier against the exterior. On the other hand, I found this intended openness very much in keeping with the theoretical principles of your manifesto, as is the idea of planting ferns and bracken along the river embankment according to the principle of a wide grid that leaves room for wild plants in the future. Am I right?

Gilles Clément Yes, you are.

Manuel Orazi In your book Le jardin en mouvement, the gardener’s aim is to organise a fragment of something larger. De Pieri remarks that very often the possible landscapes collectively seem to come knocking at the door of your gardens. In the case of the quai Branly, would you say you have created a fragment of what you yourself call a planetary intermixture?

Gilles Clément My approach to the garden of the quai Branly museum is tied into a certain aspect of the Planetary Garden: the one that I had tackled in the exhibition under the same name at la Villette in 1999-2000; and which concerned cultural (and not only natural) diversity. This, too, stems from the mechanism of civilisations’ geographical isolation from one another. What interests me here is being able to combine the respectful attitude of ancient animist civilisations towards the natural beings, with the modern attitude of ecology and its desire to meet the same necessities: to protect our environment and all the beings in it. That is why I have made use of a few symbols – such as the tortoise, frequently found in all animist societies – so as to let it be clearly understood that this garden is linked to the contents of the museum. I have also let glass surfaces into the ground, in which insects, plants and shells – beings respected by animist societies – can be observed. And some of those creatures are indeed treated as sacred, others as decorations for rituals, and others still as forms of currency.

Manuel Orazi How much time will have to pass before your garden can be fully judged?

Gilles Clément In about five years it will be comprehensible, and it will take a century to achieve a pleasant result complete with large oak trees.

Manuel Orazi You have travelled very widely, from South America to Oceania, across many of the vast territories from which the exhibits kept in the new museum originate. Do you think the open concept of your garden may constitute a European metaphor for material or artistic cultures?

Gilles Clément In my view, the cultures relating to animist societies are spiritual, not materialist. Materialism, which is at its peak in the West, originates from societies that have strayed from nature, having discounted and then marketed it. For a Yanomani Indian, air, water and herbs are not for sale. This garden enhances animist thinking and not that of the blind West.

Manuel Orazi is an architecture historian.