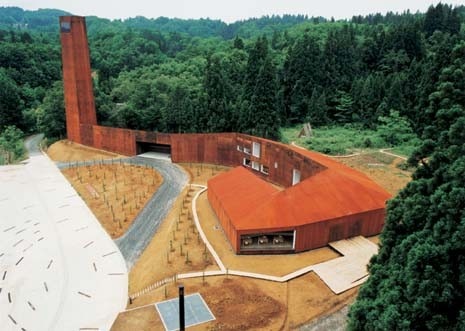

Like a cobra poised to strike, the Echigo-Matsunoyama Museum of Natural Science perches on the gentle gradient of the hillside, its tail curled around a small courtyard between the workshop spaces and the dining hall. The observation tower vigilantly keeps watch over the valley below, and the vortex-like car park by artist Tadashi Kawamata swirls around the museum’s forecourt drawing visitors towards the entrance. It’s hard for anyone who wanders around this idyllic corner of the Niigata prefecture on a mild autumn afternoon to understand the need for the 2,500 tonnes of COR-TEN steel that make up the building’s skin and structure. It is more likely that they simply dismiss it as a sculptural self-indulgence of the architect. But the visitor who returns in the early days of January will be met by a very different scene.

The road leading to the museum, kept open by snowplows, will be flanked by 5-metre high walls of ice, and the only sign of life will be from the faint glimmer of light flowing out over the pristine snowscape through the tops of the large acrylic window panels. The museum is the largest completed project to date of the Tokyo-based husband and wife team Tezuka Architects. Yui Tezuka studied architecture at the Musashi Institute of Technology and subsequently spent a year in Ron Herron’s unit at the Bartlett, London. After gaining a Master’s degree at the University of Pennsylvania in 1989, Takaharu Tezuka spent four years as an employee of the Richard Rogers Partnership, an experience that almost led the couple to settle permanently in London.

In 1994, however, an unexpected commission to design a hospital in Soejima gave the Tezukas the opportunity and impetus to cut their teeth as an independent practice on the Japanese post-bubble scene. But in the years that followed the hospital’s completion, as for so many architects of their generation, the majority of their work was in small residential projects, with the occasional medium-scale commission (a condominium for musicians, a Toyota showroom in Hiroshima). A government policy aimed at increasing the percentage of homeowners and densifying Japan’s city centres led to a nationwide boom in the construction of single-family dwellings, with a few large-scale projects being entrusted to big names in the profession. Instead of allowing a sense of frustration to set in, the Tezukas saw these small commissions, with their meagre budgets and limited impact, as an opportunity to develop a highly personal approach towards the design process.

It was based on the belief that architecture should spring from the observation of human behaviour or the manifestation of phenomena rather than the desire to produce form. Take, for example, the Roof House in Hadano, near Tokyo, a programmatic experiment devised around the client’s request that he should be able to dine on the roof. The design takes the concept much further by turning the roof into the house’s principle communal space, accessible from the living room and each family member’s bedroom.

The plot’s FAR (floor/area ratio) was thus instantly doubled and at little extra cost - no small achievement in space-starved Tokyo. The Roof House and other projects were not without their detractors, not least among the Japanese nomenklatura, who accused the Tezukas of making light of the serious matter of architecture and employing gimmicks to creep into the limelight of the popular press. Yet the instant and widespread attention the Roof House gained from the Japanese public can be attributed, according to the couple, to their desire to speak the language of everyday life and create in simple terms an architecture that can be understood and appreciated by all, not just the architectural elite.

In any case, such was the Tezuka’s notoriety that in 2003 they were featured in a TV advertisement for Toyota, and shortly afterwards a year-long documentary was filmed in their home and studio. It did no harm to the workflow as the practice completed over 40 houses between 1998 and 2003. However, making the change of scale proved a challenge, partly due to the Roof House’s controversial reception. The breakthrough came when the Tezukas were chosen as winners of the competition for the new Echigo-Matsunoyama Museum of Natural Science by a jury comprising - among others - Kazuyo Sejima, Jun Aoki and Kazuhiro Kojima.

The genesis of the project lies with Furamu Kitagawa, the coordinator of the Echigo Tsumaari Art Triennial, who was also instrumental in obtaining government funding for other projects in the Niigata region such as MVRDV’s Agrarian Culture Centre in Matsudai. These projects are an attempt to re-inject artistic vitality into rural areas largely deprived of cultural infrastructure, but also part of a long-term vision which seeks to increase the appreciation and understanding of a landscape left scarred and in decline by the lax planning laws set out in the decades following the period of “Rapid Economic Growth” of the sixties.

Echigo-Matsunoyama Museum of Natural Science bears the hallmark of the high-tech school of thought, but only in its performance-oriented philosophy. Here one finds none of the European quasi-ornamental delight in exhibiting pared down, finely engineered structural elements, but rather a simple form that is built to the pseudo-military specifications of a submarine. The museum is intended not as a beautiful container, an exercise in aesthetics per se, but a vehicle for offering the public new ways of experiencing an extreme climate.

In winter, snowfalls of 5.5 metres engulf the building; the drifts piling up on the roof would almost totally conceal it were it not for the beacon-like observation tower. As winter progresses the temperature drops to -20°C, turning the snow drifts into enormous blocks of ice that cling to its skin and exert forces of up to 1,500 kg/m2 in unexpected directions as they contract and slide down the mountainside. And that is only half the story: in summertime, the Niigata region is the hottest part of Japan with temperatures regularly reaching 45°C, causing the building’s skin to heat up to 70°C. This 90°C variation between summer and winter is enough to cause a 20cm expansion in the building’s length.

The interiors are understated, one might even say under-designed, but it doesn’t take long to realise that this serves only to emphasise the museum’s interest in engaging its surroundings and transforming them into its prime exhibit. In this sense, the line of sight is developed as a device for generating continuity: each of the tunnel-like spaces, trapezoidal in section, ends in a panoramically proportioned full-height window, causing the gaze to inevitably settle outside the building.

The visual transition between the climatically controlled interior and the extreme conditions of the exterior is unnaturally smooth, an effect heightened by the surprising clarity of the 4 metre high acrylic panels (the largest of which weighs 4 tonnes and cost around €300,000). In the snowy season, the windows become sectional devices that turn the snow’s delicate stratifications into a spectacle for all to see. It is the architect’s readily-expressed hope that the building’s lifespan will be measured in centuries, rather than decades. “If you don’t consider how your buildings will age, in ten years you’ll no longer be the architect,” Takaharu Tezuka repeats frequently to remind his students.

This comes as something of a paradox in a country where the average newly-constructed home is demolished after a mere 22 years. But if one looks to the early works of Arata Isozaki, one can find few better examples of the concept of quality: buildings that through decades of everyday use maintain the freshness and vitality of their inception. It is an obvious reference for the new generation of architects looking to counter the effects of a landscape of throw-away buildings. The Tezukas claim not to be researchers as they don’t carry out theoretical field studies or engage in large-scale mapping of urban phenomena to find points of engagement. Yet underlying each project one can perceive a subtle understanding of human behaviour in relation to its surroundings, an ongoing research into the complexities of everyday life.

Tezuka Architects

Founded in Tokyo in 1994 by Takaharu and Yui Tezuka, Tezuka Architects today has a staff of 14 people. Current projects include the Adachi Gakuen school in Tokyo, due to open in 2005, and the Fuji Kindergarten, set for completion in 2007. Takaharu Tezuka also teaches a design course at the Musashi Institute of Technology. Previous projects include the Balcony House, in which each floor is cantilevered 3.6m to offer a view unimpeded by columns and allow living spaces to be opened to the outside, and the Roof House (2001, pictured above), which despite a budget under €200,000 became one of their best-known works. The house’s roof, pitched at a ratio of 1:10, is connected to the living spaces below via skylights and ladders, and is equipped with a table and seating protected by a low wall that supports a sink and worksurface. The profile of the roof itself is kept particularly thin through the use of two layers of structural plywood inside which 105mm square section timber members are sandwiched. The same timber is used as a standard component in the construction of the house’s frame to minimise waste and overall expense.